Historicity of Muhammad

[3] Despite any difficulties with the biographical sources, scholars generally see valuable historical information about Muhammad therein and suggest that what is needed are methods to be able to sort out the likely from the unlikely.

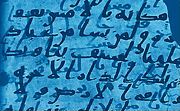

According to traditional Islamic scholarship, all of the Quran was written down by Muhammad's companions while he was alive (during CE 610–632[8]), but it was primarily an orally related document.

[3] Unlike the Bible's narratives of the life of Moses or Jesus, Michael Cook notes that while the Koran tells many stories after its fashion, that of Muhammad is not among them.

Peters),[20] with the parchment of an early copy of Quran – the Birmingham manuscript, whose text differs only slightly to modern versions – being dated to roughly around the lifetime of Muhammad.

[21] Some Western scholars,[22] however, question the accuracy of some of the Quran's historical accounts and whether the holy book existed in any form before the last decade of the seventh century (Patricia Crone and Michael Cook);[23] and/or argue it is a "cocktail of texts", some of which may have been existent a hundred years before Muhammad, that evolved (Gerd R. Puin),[23][24][25] or was redacted (J. Wansbrough),[26][27] to form the Quran.

Unlike the Quran, the hadith and sīra are devoted to Muhammad, his life, his words, deeds, approval, and example to Muslims in general.

Nearly three hundred of his documents have come down to us, including political treaties, military enlistments, assignments of officials, and state correspondence written on tanned leather.

We thus know his life to the minutest details: how he spoke, sat, slept (sic), dressed, walked; his behavior as a husband, father, nephew; his attitudes toward women, children, animals; his business transactions and stance toward the poor and the oppressed ...[28][29][30] In the sīra literature, the most important extant biography are the two recensions of Ibn Ishaq's (d. 768), now known as Sīrat Rasūl Allah ("Biography/Life of the Messenger/Apostle of Allah"), which survive in the works of his editors, most notably Ibn Hisham (d. 834) and Yunus b. Bukayr (d.814–815), although not in its original form.

[2] These are not "biographies" in the modern sense of the word, but rather accounts of Muhammad's military expeditions, his sayings, the reasons for and interpretations of verses in the Quran.

[35] According to Wim Raven, it is often noted that a coherent image of Muhammad cannot be formed from the literature of sīra, whose authenticity and factual value have been questioned on a number of different grounds.

[7] The main feature of hadith is that of Isnad (chains of transmission), which are the basis of determining the authenticity of the reports in traditional Islamic scholarship.

[47] Jonathan A. C. Brown, a Sunni Muslim American scholar of Islamic studies who follows the Hanbali school of jurisprudence,[50] asserts that the hadith tradition is a "common sense science" or a "common sense tradition" and is "one of the biggest accomplishments in human intellectual history ... in its breadth, in its depth, in its complexity and in its internal consistency.

"[51] Early Islamic history is also reflected in sources written in Greek, Syriac, Armenian, and Hebrew by Jewish and Christian communities, all of which are dated after 633 CE.

[3] According to Nevo and Koren, no Byzantine or Syriac sources provide any detail on "Muhammad's early career ... which predate the Muslim literature on the subject".

The author also talks about olive oil, cattle, ruined villages, suggesting that he belonged to peasant stock, i.e., parish priest or a monk who could read and write.

And at the turn [of the ye]ar the Romans came; and on the twentieth of August in the year n[ine hundred and forty-]seven there gathered in Gabitha [...] the Romans and great many people were ki[lled of] [the R]omans, [s]ome fifty thousand [...][58][59]The 7th-century Chronicle of 640 was published by Wright who first brought to attention the mention of an early date of 947 AG (635–36 CE).

AG 945, indiction VII: On Friday, 4 February, [i.e., 634 CE / Dhul Qa'dah 12 AH] at the ninth hour, there was a battle between the Romans and the Arabs of Maḥmet [Syr.

Some 40,000 [according to the original edition, but the more recent English translation reads "4000" without comment] poor villagers of Palestine were killed there, Christians, Jews and Samaritans.

[71] At that time a certain man from along those same sons of Ismael, whose name was Mahmet [i.e., Muḥammad], a merchant, as if by God's command appeared to them as a preacher [and] the path of truth.

[74] According to F. E. Peters, despite any difficulties with the biographical sources, scholars generally see valuable historical information about Muhammad therein and suggest that what is needed are methods to be able to sort out the likely from the unlikely.

In 1952 French Arabist Régis Blachère, author of a critical biography of Muhammad that took "fully into account the skeptical conclusions" of Ignác Goldziher and Henri Lammens, i.e. that Islamic hadith had been corrupted and could not be considered reliable sources of information, wrote We no longer have any sources that would allow us to write a detailed history of Muhammad with a rigorous and continuous chronology.

All a truly scientific biography can achieve is to lay out the successive problems engendered by this preapostolate period, sketch out the general background atmosphere in which Muhammad received his divine call, give in broad brush strokes the development of his apostleship at Mecca, try with a greater chance of success to put in order the known facts, and finally put back into the penumbra all that remains uncertain.

[75] Historian John Burton states In judging the content, the only resort of the scholar is to the yardstick of probability, and on this basis, it must be repeated, virtually nothing of use to the historian emerges from the sparse record of the early life of the founder of the latest of the great world religions ... so, however far back in the Muslim tradition one now attempts to reach, one simply cannot recover a scrap of information of real use in constructing the human history of Muhammad, beyond the bare fact that he once existed.

"[78] Overall, Cook takes the view that evidence independent of Islamic tradition "precludes any doubts as to whether Muhammad was a real person" and clearly shows that he became the central figure of a new religion in the decades following his death.

He reports, though, that this evidence conflicts with the Islamic view in some aspects, associating Muhammad with Israel rather than Inner Arabia, complicating the question of his sole authorship or transmission of the Quran, and suggesting that there were Jews as well as Arabs among his followers.

[82] Robert Hoyland suggests his historical importance may have been exaggerated by his followers, writing that "other" Arab leaders "in other locations" had preceded Muhammad in attacking the weakened Byzantine and Persian empires, but these had been "airbrushed out of history by later Muslim writers".

This has been described as "plausible or at least arguable" by David Cook of Rice University, but also compared to Holocaust denial by historian Colin Wells, who suggests that the authors deal with some of the evidence illogically.