Sources for the historicity of Jesus

[23][35][36][37][38] Although the exact nature and extent of the Christian redaction remains unclear,[39] there is broad consensus as to what the original text of the Testimonium by Josephus would have looked like.

The next thing was to seek means of propitiating the gods, and recourse was had to the Sibylline books, by the direction of which prayers were offered to Vulcanus, Ceres, and Proserpina.

Consequently, to get rid of the report, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace.

Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus, and a most mischievous superstition, thus checked for the moment, again broke out not only in Judaea, the first source of the evil, but even in Rome, where all things hideous and shameful from every part of the world find their centre and become popular.

Covered with the skins of beasts, they were torn by dogs and perished, or were nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames and burnt, to serve as a nightly illumination, when daylight had expired.

Nero offered his gardens for the spectacle, and was exhibiting a show in the circus, while he mingled with the people in the dress of a charioteer or stood aloft on a car.

Hence, even for criminals who deserved extreme and exemplary punishment, there arose a feeling of compassion; for it was not, as it seemed, for the public good, but to glut one man's cruelty, that they were being destroyed.

The Roman historian and senator Tacitus referred to Christ, his execution by Pontius Pilate and the existence of early Christians in Rome in his final work, Annals (c. 116 CE), book 15, chapter 44.

[47][48][49][50][51] William L. Portier has stated that the consistency in the references by Tacitus, Josephus and the letters to Emperor Trajan by Pliny the Younger reaffirm the validity of all three accounts.

"[57] Bart D. Ehrman states: "Tacitus's report confirms what we know from other sources, that Jesus was executed by order of the Roman governor of Judea, Pontius Pilate, sometime during Tiberius's reign.

"[58] Paul Rhodes Eddy and Gregory A. Boyd state that it is now "firmly established" that Tacitus provides a non-Christian confirmation of the crucifixion of Jesus.

[69] Classicists observe that Carrier’s thesis is outdated, not supported on textual grounds, nor is there any evidence of this non-Christian group existing and is thus dismissed by classical scholars.

[63] Tacitus was a member of the Quindecimviri sacris faciundis, a council of priests whose duty it was to supervise foreign religious cults in Rome, which as Van Voorst points out, makes it reasonable to suppose that he would have acquired knowledge of Christian origins through his work with that body.

[101] Bart Ehrman and separately Mark Allan Powell state that given that the Talmud references are quite late, they can give no historically reliable information about the teachings or actions of Jesus during his life.

[92] R. T. France and separately Edgar V. McKnight state that the divergence of the Talmud statements from the Christian accounts and their negative nature indicate that they are about a person who existed.

[106][107] Craig Blomberg states that the denial of the existence of Jesus was never part of the Jewish tradition, which instead accused him of being a sorcerer and magician, as also reflected in other sources such as Celsus.

[90] Andreas Kostenberger states that the overall conclusion that can be drawn from the references in the Talmud is that Jesus was a historical person whose existence was never denied by the Jewish tradition, which instead focused on discrediting him.

[109][110] It is not known whether Thallus made any mention to the crucifixion accounts; if he did and the dating is accurate, it would be the earliest noncanonical reference to a gospel episode, but its usefulness in determining the historicity of Jesus is uncertain.

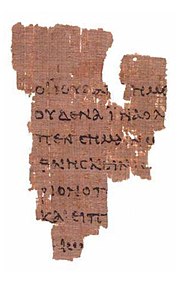

[136] Blainey writes that the oldest surviving record written by an early Christian is a short letter by St Paul: the First Epistle to the Thessalonians, which appeared about 25 years after the death of Jesus.

[144] From Paul's writings alone, a fairly full outline of the life of Jesus can found: his descent from Abraham and David, his upbringing in the Jewish Law, gathering together disciples, including Cephas (Peter) and John, having a brother named James, living an exemplary life, the Last Supper and betrayal, numerous details surrounding his death and resurrection (e.g. crucifixion, Jewish involvement in putting him to death, burial, resurrection, seen by Peter, James, the twelve and others) along with numerous quotations referring to notable teachings and events found in the Gospels.

[151][155] In Paul's view, the earthly life of Jesus was of lower importance than the theology of his death and resurrection, a theme that permeates Pauline writings.

[178] Concerning this creed, Campenhausen wrote, "This account meets all the demands of historical reliability that could possibly be made of such a text,"[179] whilst A. M. Hunter said, "The passage therefore preserves uniquely early and verifiable testimony.

[181] The four canonical gospels, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, are the main sources for the biography of Jesus' life, the teachings and actions attributed to him.

[182][183][184] Three of these (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) are known as the synoptic Gospels, from the Greek σύν (syn "together") and ὄψις (opsis "view"), given that they display a high degree of similarity in content, narrative arrangement, language and paragraph structure.

[187] The authors of the New Testament generally showed little interest in an absolute chronology of Jesus or in synchronizing the episodes of his life with the secular history of the age.

[189] One manifestation of the gospels being theological documents rather than historical chronicles is that they devote about one third of their text to just seven days, namely the last week of the life of Jesus in Jerusalem.

[190] Although the gospels do not provide enough details to satisfy the demands of modern historians regarding exact dates, scholars have used them to reconstruct a number of portraits of Jesus.

Sanders and separately Craig A. Evans go further and assume that two other events in the gospels are historically certain, namely that Jesus called disciples, and caused a controversy at the Temple.

[209] However, the trend among the 21st century scholars has been to accept that while the gnostic gospels may shed light on the progression of early Christian beliefs, they offer very little to contribute to the study of the historicity of Jesus, in that they are rather late writings, usually consisting of sayings (rather than narrative, similar to the hypothesised Q documents), their authenticity and authorship remain questionable, and various parts of them rely on components of the New Testament.

[213] While research on apocryphal texts continues, the general scholarly opinion holds that they have little to offer to the study of the historicity of Jesus given that they are often of uncertain origin, and almost always later documents of lower value.