Historiography of the fall of the Western Roman Empire

Gibbon's criticism of Christianity reflects the values of the Enlightenment; his ideas on the decline in martial vigor could have been interpreted by some as a warning to the growing British Empire.

More recently, environmental concerns have become popular, with deforestation and soil erosion proposed as major factors, and destabilizing population decreases due to epidemics such as early cases of bubonic plague and malaria also cited.

What is not new are attempts to diagnose Rome's particular problems; already in the early 2nd century, at the height of Roman power, Juvenal in his Satire X criticized the people's obsession with "bread and circuses".

[citation needed] In that year there was an unmanageable influx of Goths and other Barbarians into the Balkan provinces, and the situation of the Western Empire generally worsened thereafter, despite incomplete and temporary recoveries.

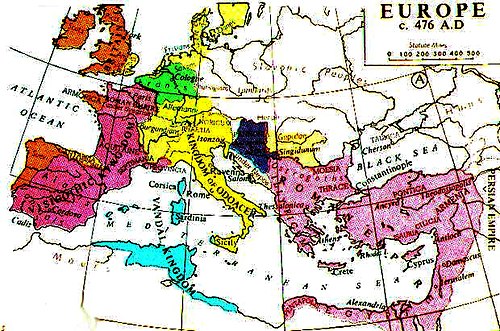

Throughout the 5th century, the Empire's territories in western Europe and northwestern Africa, including Italy, fell to various invading or indigenous peoples in what is sometimes called the Migration period.

Saint Augustine wrote The City of God partly as an answer to critics who blamed the sack of Rome by the Visigoths on the abandonment of the traditional pagan religions.

[9] The "long peace" that ended with Marcus, in his view, "introduced a slow and secret poison into the vitals of the empire[10]....The decline of Rome was the natural and inevitable effect of immoderate greatness.

Prosperity ripened the principle of decay; the causes of destruction multiplied with the extent of conquest; and as soon as time or accident had removed the artificial supports, the stupendous fabric yielded to the pressure of its own weight.

[24] Christianity typified superstition in Gibbon's view, and its spirituality was subversive of the traditional Roman virtues (IV, 162), but monks and eunuchs were not agents of social change so much as they were symptoms of a decline already taking place.

The historian Arther Ferrill has suggested that the Roman Empire – particularly the military – declined largely as a result of an influx of Germanic mercenaries into the ranks of the legions.

[29]Historian Michael Rostovtzeff and economist Ludwig von Mises both argued that unsound economic policies played a key role in the impoverishment and decay of the Roman Empire.

Using Marxist terms, Rostovtzeff in 1926 argued that the roots of Roman decline were the "alliance of the [regressive] elements of the rural proletariat with the military destroyed the beneficient rule of an urban bourgeoisie.

When a society confronts a "problem", such as a shortage of or difficulty in gaining access to energy, it tends to create new layers of bureaucracy, infrastructure, or social class to address the challenge.

The army still remained a superior fighting instrument to its opponents, both civilized and barbarian; this is shown in the victories over Germanic tribes at the Battle of Strasbourg (357) and in its ability to hold the line against the Sassanid Persians throughout the 4th century.

But, says Goldsworthy, "Weakening central authority, social and economic problems and, most of all, the continuing grind of civil wars eroded the political capacity to maintain the army at this level.

[citation needed] Publishing several articles in the 1960s, the sociologist S. Colum Gilfillan advanced the argument that lead poisoning was a significant factor in the decline of the Roman Empire.

His work centred on the level to which the ancient Romans, who had few sweeteners besides honey, would boil must in lead pots to produce a reduced sugar syrup called defrutum, concentrated again into sapa.

[41] John Scarborough, a pharmacologist and classicist, criticized Nriagu's book as "so full of false evidence, miscitations, typographical errors, and a blatant flippancy regarding primary sources that the reader cannot trust the basic arguments.

No general causes can be assigned that made it inevitable.Bury held that a number of crises arose simultaneously: economic decline, Germanic expansion, depopulation of Italy, dependency on Germanic foederati for the military, the disastrous (though Bury believed unknowing) treason of Stilicho, loss of martial vigor, Aetius' murder, the lack of any leader to replace Aetius – a series of misfortunes which, in combination, proved catastrophic: The Empire had come to depend on the enrollment of barbarians, in large numbers, in the army, and ... it was necessary to render the service attractive to them by the prospect of power and wealth.

The point of the present contention is that Rome's loss of her provinces in the fifth century was not an "inevitable effect of any of those features which have been rightly or wrongly described as causes or consequences of her general 'decline'".

The central fact that Rome could not dispense with the help of barbarians for her wars (gentium barbararum auxilio indigemus) may be held to be the cause of her calamities, but it was a weakness which might have continued to be far short of fatal but for the sequence of contingencies pointed out above.

[47]Heather goes on to state – in the tradition of Gibbon and Bury – that it took the Roman Empire about half a century to cope with the Sassanid threat, which it did by stripping the western provincial towns and cities of their regional taxation income.

The resulting expansion of military forces in the Middle East was finally successful in stabilizing the frontiers with the Sassanids, but the reduction of real income in the provinces of the Empire led to two trends which, Heather says, had a negative long-term impact.

"[48] Having set the scene of an Empire stretched militarily by the Sassanid threat, Heather then suggests, using archaeological evidence, that by 400 the Germanic tribes of Europe had "increased substantially in size and wealth" since the first century.

[51] Bryan Ward-Perkins's The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization (2005) takes a traditional view tempered by modern discoveries, arguing that the empire's demise was caused by a vicious circle of political instability, foreign invasion, and reduced tax revenue.

Islamic conquest of the area of today's south-eastern Turkey, Syria, Palestine, North Africa, Spain and Portugal ruptured economic ties to western Europe, cutting the region off from trade and turning it into a stagnant backwater, with wealth flowing out in the form of raw resources and nothing coming back.

Pirenne's view on the continuity of the Roman Empire before and after the Germanic invasion has been supported by recent historians such as François Masai, Karl Ferdinand Werner, and Peter Brown.

In the spirit of "Pirenne thesis", a school of thought pictured a clash of civilizations between the Roman and the Germanic world, a process taking place roughly between 3rd and 8th century.

To support this conclusion, beside the narrative of the events, he offers linguistic surveys of toponymy and anthroponymy, analyzes archaeological records, studies the urban and rural society, the institutions, the religion, the art, and the technology.

Historians of Late Antiquity, a field pioneered by Peter Brown, have turned away from the idea that the Roman Empire fell at all – refocusing instead on Pirenne's thesis.