History of the Cape Colony from 1870 to 1899

The ensuing years saw a rapid surge in economic growth, a country-wide expansion of infrastructure as well as a period of regional integration and social development.

They also criticised the timing of the scheme as particularly unfortunate – coming when the different states of Southern Africa were still unstable and simmering after the last bout of British imperial expansion.

It also suspected him of manoeuvring to consolidate British control over the region's states, reverse the Cape's independence, and bring on a war with the neighbouring Xhosa Chiefs.

However, the general public in South Africa saw him as a representative of the British government and local suspicion of his agenda ensured that his trip was not a success; in fact he entirely failed to induce Southern Africans to adopt Lord Carnarvon's confederation system.

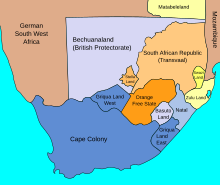

The Molteno Unification Plan (1877), put forward by the Cape government as a more feasible unitary alternative to confederation, largely anticipated the final act of Union in 1909.

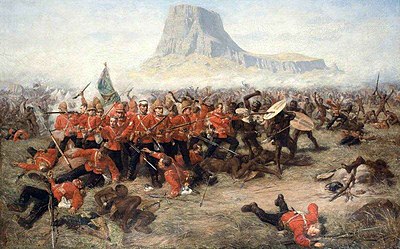

Frere's dissolving of the elected Cape Government removed any constitutional obstructions to the colonial office's confederation plan, but was overshadowed by growing unrest and anti-British agitation across the whole region.

With the Cape government removed and a puppet Prime Minister (John Gordon Sprigg) installed, Frere turned to the Zulu Kingdom to the east, under its King, Cetshwayo.

The delay in giving the country a constitution afforded a pretext for agitation to the discontented Boers, a rapidly increasing minority, while the reverse at Isandlwana had lowered British prestige.

On his return to Cape Town, Frere found that his achievement had been eclipsed—first by 1 June 1879 death of Napoleon Eugene, Prince Imperial, in Zululand, and then by the news that the government of the Transvaal and Natal, together with the high commissionership for the south-eastern part of South Africa, had been transferred from him to Sir Garnet Wolseley.

However, these clauses were meaningless in the view of the government in Cape Colony, for Article 3 on the manifesto advocated complete independence (Zelfstandieheid) for South Africa, which was tantamount to treason against the Crown.

A pamphlet written in 1885 for an association called the Empire League on the behalf of the Bond, stated the following: From 1881 onwards, two contrasting political ideas developed in the Cape Colony regarding imperial expansion, universal suffrage and self-government.

Cecil Rhodes recognised the difficulties of his position and showed a desire to conciliate Dutch sentiment by considerate treatment from the outset of his political career.

He supported the bill permitting the use of Dutch in the House of Assembly in 1882, and, early in 1884, he was appointed to his first ministerial post as treasurer-general under Sir Thomas Scanlen.

Sir Hercules Robinson sent him to British Bechuanaland in August 1884 as deputy-commissioner to succeed Reverend John Mackenzie, the London Missionary Society's representative at Kuruman, who proclaimed Queen Victoria's authority over the district in May 1883.

At this conference, Hofmeyr proposed a sort of "Zollverein" scheme, in which imperial customs were to be levied independently of the duties payable on all goods entering the empire from abroad.

In spite of the disastrous failure of political confederation, the members of the Cape parliament set about establishing a South African Customs Union in 1888.

There was the first of many attempts to get the Transvaal to join, but President Kruger, who was pursuing his own policy, hoped to make the South African Republic entirely independent of Cape Colony through the Delagoa Bay railway.

Another event of considerable commercial importance to the Cape Colony, and indeed to all of South Africa, was the amalgamation of the diamond-mining companies which was chiefly brought about by Cecil Rhodes, Alfred Beit and "Barney" Barnato in 1889.

His policy of customs and railway unions between the various states when added to the personal esteem which many Dutchmen at the time had for him, enabled him to undertake and to successfully carry out the business of government.

Rhodes opposed native liquor trafficking and suppressed it entirely on the diamond mines at the risk of offending some of his supporters among the brandy-farmers of the western provinces.

A little-known instance of Rhode's keen insight in native affairs that had lasting results on the history of the colony is his actions in an inheritance case.

With the development of railways and the increase in trade between Cape Colony and the Transvaal, politicians in both places began to debate forming a closer relationship.

He hoped to established both a commercial and a railway union, which is illustrated by a speech he gave in 1894 in Cape Town: President Kruger and the Transvaal government found every possible objection to this policy.

It is evident from President Kruger's subsequent actions that these changes were based upon his personal approval with the goal of compelling traffic to the Transvaal to use the Delagoa route instead of the colonial railway.

These terms were accepted by Rhodes and his colleagues, of whom W. P. Schreiner was one, and a protest was sent by Chamberlain stating that the government regarded the closing of the drifts as a breach of the London Convention, and as an unfriendly action that called for the gravest of responses.

Leander Starr Jameson made his famous raid into the Transvaal on 29 December 1895, and Rhode's complicity in the action compelled him to resign the premiership of Cape Colony in January 1896.

Schreiner asked the high commissioner on 11 June 1899 to inform Chamberlain that he and his colleagues decided to accept President Kruger's Bloemfontein proposals as "practical, reasonable and a considerable step in the right direction".

Unfortunately, Hofmeyr's influence was more than counterbalanced by an emissary from the Free State named Abraham Fischer who while purporting to be a peacemaker, practically encouraged the Boer executive to take extreme measures.

Meanwhile, the Boer executive drafted a new proposal which prompted Schreiner to write a letter on 7 July to the South African News, in which while referring to his own government, he said: "While anxious and continually active with good hope in the cause of securing reasonable modifications of the existing representative system of the South African Republic, this government is convinced that no ground whatever exists for active interference in the internal affairs of that republic".

He demonstrated the same inability to understand the uitlanders' grievances, the same futile belief in the eventual fairness of President Kruger as premier of Cape Colony as he had shown when giving evidence before the British South Africa Select Committee into the causes of the Jameson Raid.