History of English

A significant subsequent influence upon the shaping of Old English came from contact with the North Germanic languages spoken by the Scandinavian Vikings who conquered and colonized parts of Britain during the 8th and 9th centuries, which led to much lexical borrowing and grammatical simplification.

Many Norman and French loanwords entered the local language in this period, especially in vocabulary related to the church, the court system and the government.

It incorporated many Renaissance-era loans from Latin and Ancient Greek, as well as borrowings from other European languages, including French, German and Dutch.

This is especially true in Europe, where English has largely taken over the former roles of French and, much earlier, Latin as a common language used to conduct business and diplomacy, share scientific and technological information, and otherwise communicate across national boundaries.

They consisted of dialects from the Ingvaeonic grouping, spoken mainly around the North Sea coast, in regions that lie within modern Denmark, north-west Germany and the Netherlands.

Due to specific similarities between early English and Old Frisian, an Anglo-Frisian grouping is also identified, although it does not necessarily represent a node in the family tree.

The Germanic settlers in the British Isles initially spoke a number of different dialects, which developed into a language that came to be called Anglo-Saxon.

[11] The speech of eastern and northern parts of England was also subject to strong Old Norse influence due to Scandinavian rule and settlement beginning in the 9th century (see below).

In 865, a major invasion was launched by what the Anglo-Saxons called the Great Heathen Army, which eventually brought large parts of northern and eastern England, the Danelaw, under Scandinavian control.

Most of these areas were retaken by the English under Edward the Elder in the early 10th century, although York and Northumbria were not permanently regained until the death of Eric Bloodaxe in 954.

During the rule of Cnut and other Danish kings in the first half of the 11th century, a kind of diglossia may have come about, with the West Saxon literary language existing alongside the Norse-influenced Midland dialect of English, which could have served as a koine or spoken lingua franca.

Later texts from the Middle English era, now based on an eastern Midland rather than a Wessex standard, reflect the significant impact that Norse had on the language.

[16] Norse borrowings include many very common words, such as anger, bag, both, hit, law, leg, same, skill, sky, take, window, and even the pronoun they.

It is considered to have stimulated and accelerated the morphological simplification found in Middle English, such as the loss of grammatical gender and explicitly marked case, except in pronouns.

About 10,000 French and Norman loan words entered Middle English, particularly terms associated with government, church, law, the military, fashion, and food.

Geoffrey Chaucer, who lived in the late 14th century, is the most famous writer from the Middle English period, and The Canterbury Tales is his best-known work.

Increased literacy and travel facilitated the adoption of many foreign words, especially borrowings from Latin and Greek, often terms for abstract concepts not available in English.

As there are many words from different languages and English spelling is variable, the risk of mispronunciation is high, but remnants of the older forms remain in a few regional dialects, most notably in the West Country.

The British Empire at its height covered one quarter of the Earth's land surface, and the English language adopted foreign words from many countries.

The most important umlaut process was *i-mutation, c. 500 CE, which led to pervasive alternations of all sorts, many of which survive in the modern language: e.g. in noun paradigms (foot vs. feet, mouse vs. mice, brother vs. brethren); in verb paradigms (sold vs. sell); nominal derivatives from adjectives ("strong" vs. "strength", broad vs. breadth, foul vs. filth) and from other nouns (fox vs. "vixen"); verbal derivatives ("food" vs. "to feed"); and comparative adjectives ("old" vs. "elder").

This occurred after the spelling system was fixed, and accounts for the drastic differences in pronunciation between "short" mat, met, bit, cot vs. "long" mate, mete/meet, bite, coat.

Other changes that left echoes in the modern language were homorganic lengthening before ld, mb, nd, which accounts for the long vowels in child, mind, climb, etc.

Among the more significant recent changes to the language have been the development of rhotic and non-rhotic accents (i.e. "r-dropping") and the trap-bath split in many dialects of British English.

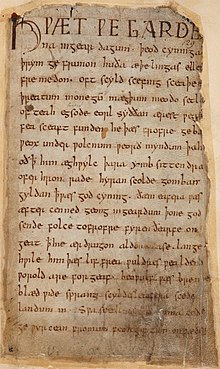

These are the first 11 lines: Which, as translated by Francis Barton Gummere, reads: Lo, praise of the prowess of people-kings of spear-armed Danes, in days long sped, we have heard, and what honor the athelings won!

Since erst he lay friendless, a foundling, fate repaid him: for he waxed under welkin, in wealth he throve, till before him the folk, both far and near, who house by the whale-path, heard his mandate, gave him gifts: a good king he!

Þā Boermas heafdon sīþe wel gebūd hira land: ac hīe ne dorston þǣr on cuman.

He said though that the land was very long from there, but it is all wasteland, except that in a few places here and there Finns [i.e. Sami] encamp, hunting in winter and in summer fishing by the sea.

The beginning of The Canterbury Tales, a collection of stories in poetry and prose written in the London dialect of Middle English by Geoffrey Chaucer, at the end of the 14th century:[37] Whan that Aprill with his shoures soote The droghte of March hath perced to the roote, And bathed every veyne in swich licour Of which vertu engendred is the flour; Whan Zephirus eek with his sweete breeth Inspired hath in every holt and heeth The tendre croppes, and the yonge sonne Hath in the Ram his half cours yronne, And smale foweles maken melodye, That slepen al the nyght with open yë (So priketh hem nature in hir corages), Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages, And palmeres for to seken straunge strondes, To ferne halwes, kowthe in sondry londes; And specially from every shires ende Of Engelond to Caunterbury they wende, The hooly blisful martir for to seke, That hem hath holpen whan that they were seeke.

The beginning of Paradise Lost, an epic poem in unrhymed iambic pentameter written in Early Modern English by John Milton, first published in 1667: Of Mans First Disobedience, and the Fruit Of that Forbidden Tree, whose mortal tast Brought Death into the World, and all our woe, With loss of Eden, till one greater Man Restore us, and regain the blissful Seat, Sing Heav'nly Muse, that on the secret top Of Oreb, or of Sinai, didst inspire That Shepherd, who first taught the chosen Seed, In the Beginning how the Heav'ns and Earth Rose out of Chaos: Or if Sion Hill Delight thee more, and Siloa's Brook that flow'd Fast by the Oracle of God; I thence Invoke thy aid to my adventrous Song, That with no middle flight intends to soar Above th' Aonian Mount, while it pursues Things unattempted yet in Prose or Rhime.

A selection from the novel Oliver Twist, written by Charles Dickens in Modern English and published in 1838: The evening arrived: the boys took their places; the master in his cook's uniform stationed himself at the copper; his pauper assistants ranged themselves behind him; the gruel was served out, and a long grace was said over the short commons.

Anglo-Norman French , then French : ~29%

Latin , including words used only in scientific, medical or legal contexts: ~29%

Germanic : ~26%

Others: ~16%