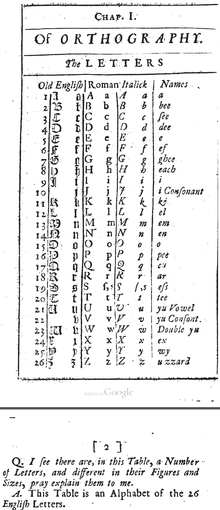

English alphabet

Modern English is written with a Latin-script alphabet consisting of 26 letters, with each having both uppercase and lowercase forms.

The names of the letters are commonly spelled out in compound words and initialisms (e.g., tee-shirt, deejay, emcee, okay, etc.

Plurals of consonant names are formed by adding -s (e.g., bees, efs or effs, ems) or -es in the cases of aitches, esses, exes.

Plurals of vowel names also take -es (i.e., aes, ees, ies, oes, ues), but these are rare.

The regular phonological developments (in rough chronological order) are: The novel forms are aitch, a regular development of Medieval Latin acca; jay, a new letter presumably vocalised like neighboring kay to avoid confusion with established gee (the other name, jy, was taken from French); vee, a new letter named by analogy with the majority; double-u, a new letter, self-explanatory (the name of Latin V was ū); wye, of obscure origin but with an antecedent in Old French wi; izzard, from the Romance phrase i zed or i zeto "and Z" said when reciting the alphabet; and zee, an American levelling of zed by analogy with other consonants.

Some groups of letters, such as pee and bee, or em and en, are easily confused in speech, especially when heard over the telephone or a radio communications link.

The most common diacritic marks seen in English publications are the acute (é), grave (è), circumflex (â, î, or ô), tilde (ñ), umlaut and diaeresis (ü or ï—the same symbol is used for two different purposes), and cedilla (ç).

As such words become naturalised in English, there is a tendency to drop the diacritics, as has happened with many older borrowings from French, such as hôtel.

Words that are still perceived as foreign tend to retain them; for example, the only spelling of soupçon found in English dictionaries (the OED and others) uses the diacritic.

Written compound words may be hyphenated, open or closed, so specifics are guided by stylistic policy.

The Latin script, introduced by Christian missionaries, began to replace the Anglo-Saxon futhorc from about the 7th century, although the two continued in parallel for some time.

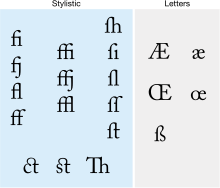

The letter eth (Ð ð) was later devised as a modification of dee (D d), and finally yogh (Ȝ ȝ) was created by Norman scribes from the insular g in Old English and Irish, and used alongside their Carolingian g. The a-e ligature ash (Æ æ) was adopted as a letter in its own right, named after a futhorc rune æsc.

In the year 1011, a monk named Byrhtferð recorded the traditional order of the Old English alphabet.

Latin borrowings reintroduced homographs of æ and œ into Middle English and Early Modern English, though they are largely obsolete (see "Ligatures in recent usage" below), and where they are used they are not considered to be separate letters (e.g., for collation purposes), but rather ligatures.

The ligatures æ and œ were until the 19th century (slightly later in American English)[citation needed] used in formal writing for certain words of Greek or Latin origin, such as encyclopædia and cœlom, although such ligatures were not used in either classical Latin or ancient Greek.

These are now usually rendered as "ae" and "oe" in all types of writing,[citation needed] although in American English, a lone e has mostly supplanted both (for example, encyclopedia for encyclopaedia, and maneuver for manoeuvre).