History of Solar System formation and evolution hypotheses

This model posits that, 4.6 billion years ago, the Solar System was formed by the gravitational collapse of a giant molecular cloud spanning several light-years.

However, material would be colliding at a high relative velocity in the inter-vortex boundaries and, in these regions, small roller-bearing eddies would coalesce to give annular condensations.

[5] This model was modified[4] in 1948 by Dutch theoretical physicist Dirk Ter Haar, who hypothesized that regular eddies were discarded and replaced by random turbulence, which would lead to a very thick nebula where gravitational instability would not occur.

In 1796, Laplace elaborated by arguing that the nebula collapsed into a star, and, as it did so, the remaining material gradually spun outward into a flat disc, which then formed planets.

[8] However plausible it may appear at first sight, the nebular hypothesis still faces the obstacle of angular momentum; if the Sun had indeed formed from the collapse of such a cloud, the planets should be rotating far more slowly.

Attempts to resolve the angular momentum problem led to the temporary abandonment of the nebular hypothesis in favor of a return to "two-body" hypotheses.

[8] For several decades, many astronomers preferred the tidal or near-collision hypothesis put forward by James Jeans in 1917, in which the approach of some other star to the Sun ultimately formed the solar system.

[11] Along with many astronomers of the time, they came to believe the pictures of "spiral nebulas" from the Lick Observatory were direct evidence of the formation of planetary systems, which later turned out to be galaxies.

[clarification needed] In 1954, 1975, and 1978,[12] Swedish astrophysicist Hannes Alfvén included electromagnetic effects in equations of particle motions, and angular momentum distribution and compositional differences were explained.

[8] Ray Lyttleton modified the hypothesis by showing that a third body was not necessary and proposing that a mechanism of line accretion, as described by Bondi and Hoyle in 1944, enabled cloud material to be captured by the star (Williams and Cremin, 1968, loc.

Gerard Kuiper in 1944[4] argued, like Ter Haar, that regular eddies would be impossible and postulated that large gravitational instabilities might occur in the solar nebula, forming condensations.

The protoplanets might have heated up to such high degrees that the more volatile compounds would have been lost, and the orbital velocity decreased with increasing distance so that the terrestrial planets would have been more affected.

This hypothesis has some problems, such as failing to explain the fact that the planets all orbit the Sun in the same direction with relatively low eccentricity, which would appear highly unlikely if they were each individually captured.

[8] In American astronomer Alastair G. W. Cameron's hypothesis from 1962 and 1963,[4] the protosun, with a mass of about 1–2 Suns and a diameter of around 100,000 AU, was gravitationally unstable, collapsed, and broke into smaller subunits.

At this stage, radiation removed excess energy, the disk would cool over a relatively short period of about 1 million years, and the condensation into what Whipple calls cometismals took place.

The capture hypothesis, proposed by Michael Mark Woolfson in 1964, posits that the Solar System formed from tidal interactions between the Sun and a low-density protostar.

In the revised version from 1999 and later, the original Solar System had six pairs of twin planets, and each fissioned off from the equatorial bulges of an overspinning Sun, where outward centrifugal forces exceeded the inward gravitational force, at different times, giving them different temperatures, sizes, and compositions, and having condensed thereafter with the nebular disk dissipating after some 100 million years, with six planets exploding.

He refers to his model as "indivisible" – meaning that the fundamental aspects of Earth are connected logically and causally and can be deduced from its early formation as a Jupiter-like giant.

In 1944, German chemist and physicist Arnold Eucken considered the thermodynamics of Earth condensing and raining-out within a giant protoplanet at pressures of 100–1000 atm.

[8][28] Prentice also suggested that the young Sun transferred some angular momentum to the protoplanetary disc and planetesimals through supersonic ejections understood to occur in T Tauri stars.

[8] The birth of the modern, widely accepted hypothesis of planetary formation, the Solar Nebular Disk Model (SNDM), can be traced to the works of Soviet astronomer Victor Safronov.

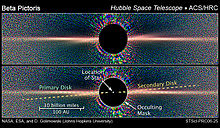

It was not confidently assumed to be widely applicable to other planetary systems, although scientists were anxious to test the nebular model by finding protoplanetary discs or even planets around other stars.

[36][37] There is no consensus on how to explain these so-called hot Jupiters, but one leading idea is that of planetary migration, similar to the process which is thought to have moved Uranus and Neptune to their current, distant orbit.

)[45] Albert Einstein's development of the theory of relativity in 1905 led to the understanding that nuclear reactions could create new elements from smaller precursors with the loss of energy.

However, in 1952, physicist Ed Salpeter showed that a short enough time existed between the formation and the decay of the beryllium isotope that another helium had a small chance to form carbon, but only if their combined mass/energy amounts were equal to that of carbon-12.

[51][52] In 1910, Henry Norris Russell, Edward Charles Pickering, and Williamina Fleming discovered that, despite being a dim star, 40 Eridani B was of spectral type A, or white.

[56] Such densities are possible because white dwarf material is not composed of atoms bound by chemical bonds, but rather consists of a plasma of unbound nuclei and electrons.

[3] The existing hypotheses were all refuted by the Apollo lunar missions in the late 1960s and early 1970s, which introduced a stream of new scientific evidence, specifically concerning the Moon's composition, age, and history.

Originally formulated by two independent research groups in 1976, the giant impact model supposed that a massive planetary object the size of Mars had collided with Earth early in its history.

[3] While the co-accretion and capture models are not currently accepted as valid explanations for the existence of the Moon, they have been employed to explain the formation of other natural satellites in the Solar System.