History of St. Louis (1804–1865)

The history of St. Louis, Missouri from 1804 to 1865 included the creation of St. Louis as the territorial capital of the Louisiana Territory, a brief period of growth until the Panic of 1819 and subsequent depression, rapid diversification of industry after the introduction of the steamboat and the return of prosperity, and rising tensions about the issues of immigration and slavery.

[1] Stoddard quickly established a citizens' committee (led by leading Creole families) to write local regulations.

[1] The act also banned the foreign slave trade and nullified any land grants greater than 640 acres made after October 1, 1800.

[2] Most wealthy Creoles found the new organization law to be particularly repulsive, if not for its threat toward slavery then due to its reduction of the significance of St.

[2] The Creole families and Americans who held large Spanish land grants thus petitioned Congress in 1804 to review the system.

[4] By 1806, Wilkinson had become widely unpopular in St. Louis due to his interference with the land claims review board and refusal to convene a territorial legislature.

[7] The population of the city expanded slowly after the Louisiana Purchase, but with expansion came increased desire to incorporate St. Louis as a town, allowing it to create local ordinances without the approval of the territorial legislature.

[9] The district and town jail was located in the former masonry tower, known as Fort San Carlos, built by Leyba for the Battle of St. Louis in 1780.

[23] Protestants began to receive services in their homes led by itinerant ministers starting in the late 1790s, but most were quickly required to remove to American territory prior to the Louisiana Purchase.

[26] Benefiting from the expertise of these traders was the Lewis and Clark Expedition, which left St. Louis in May 1804, reached the Pacific Ocean in the summer of 1805, and returned on September 23, 1806.

The fur trade remained the basis of the wealth of elite St. Louis Creole families such as the Chouteaus well into the early 1820s.

Starting in the early 1810s with the growth of American families moving to St. Louis, brick buildings began to be built in the town.

[27] These early American and immigrant families began opening new businesses, including printing and banking, starting in the 1810s.

[18] By 1824 and 1825, however, St. Louis businesses began outfitting an increasing number of farmers going west, while other merchants supplied military forces going to western outposts.

[34] Diversification in products available in St. Louis took place during the economic recovery, largely as a result of the new steamboat power.

[35] Confectioneries, jewelers, bookstores, musical instrument shops, lumber yards, and mortuaries all opened for the first time in the late 1820s and 1830s.

[40] The construction of the Old St. Louis County Courthouse in the late 1820s encouraged other growth, with an addition of western lots to Ninth Street and a new city hall adjacent to the river in 1833.

[citation needed] In large part due to the rapid growth of the 1830s and 1840s, cholera became a significant problem in St. Louis.

[46][47] As a solution to the cholera problem, city officials constructed a sewer system to drain sinkholes that had become clogged with sewage and garbage.

[50] Property losses were estimated at $6.1 million, while thousands became unemployed, hundreds lost their homes, and dozens of major businesses were destroyed.

[50] In response to the fire, streets were widened, the wharf was improved,[51] and a new building code required structures to be built of stone or brick.

[54][55] Starting in 1830, a pumping station and reservoir was built on top of a Native American mound, but it quickly became inadequate to the city's needs.

[60] Initially the schools required students to pay fees, but by 1847 tax levies allowed for free public education and expansion of the system.

Many free blacks and slaves lived and worked in St. Louis, as domestics, artisans, crew on the riverboats and laborers at the wharves.

[63] Many slaves worked on steamboats as crew or as laborers on the riverfront, and some escaped across the river to the free state of Illinois, continuing via the Underground Railroad to Canada.

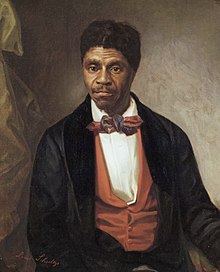

[67] In 1846, the slaves Dred Scott and his wife Harriet sued for freedom, in a case heard at the Old Courthouse, based on their having traveled and lived with their master in free states.

[77] Benton was a solid member of the Democratic Party and was supported by newly naturalized and lower-class Germans and Irish.

[77] He faced Luther M. Kennett, who had garnered the support of the disintegrating Whig Party (including the wealthy St. Louis elite class) and the nativist Know Nothing movement.

[78] The Irish and dockworkers retreated to boarding houses, at which point the nativists began attacking Saint Louis University and German newspaper offices.

[78] The St. Louis police department and local militia eventually quelled the riot, though not before 10 were killed, 33 wounded, and 93 buildings were damaged.