History of United States prison systems

In colonial times, courts and magistrates would impose punishments including fines, forced labor, public restraint, flogging, maiming, and death, with sheriffs detaining some defendants awaiting trial.

According to Bruce Johnston, "of course the notion of forcibly confining people is ancient, and there is extensive evidence that the Romans had a well developed system for imprisoning different types of offenders"[8] It wasn't until 1789 when reform started taking place in America.

[13] Throughout the 1700s, even as England's "Bloody Code" took shape, incarceration at hard labor was held out as an acceptable punishment for criminals of various kinds—e.g., those who received a suspended death sentence via the benefit of clergy or a pardon, those who were not transported to the colonies, or those convicted of petty larceny.

Beginning with Samuel Denne's Letter to Lord Ladbroke (1771) and Jonas Hanway's Solitude in Imprisonment (1776), philanthropic literature on English penal reform began to concentrate on the post-conviction rehabilitation of criminals in the prison setting.

[20] A major political obstacle to implementing the philanthropists' solitary program in England was financial: Building individual cells for each prisoner cost more than the congregate housing arrangements typical of eighteenth-century English jails.

Philadelphians of the period eagerly followed the reports of philanthropist reformer John Howard[16] And the archetypical penitentiaries that emerged in the 1820s United States—e.g., Auburn and Eastern State penitentiaries—both implemented a solitary regime aimed at morally rehabilitating prisoners.

[26] Although convicts played a significant role in British settlement of North America, according to legal historian Adam J. Hirsch "[t]he wholesale incarceration of criminals is in truth a comparatively recent episode in the history of Anglo-American jurisprudence.

"[31] The Virginia Company, the corporate entity responsible for settling Jamestown, authorized its colonists to seize Native American children wherever they could "for conversion ... to the knowledge and worship of the true God and their redeemer, Christ Jesus.

[31] When control of the Virginia Company passed to Sir Edwin Sandys in 1618, efforts to bring large numbers of settlers to the New World against their will gained traction alongside less coercive measures like indentured servitude.

[49] Dr. Samuel Johnson, upon hearing that British authorities might bow to continuing agitation in the American colonies against transportation, reportedly told James Boswell: "Why they are a race of convicts, and ought to be thankful for anything we allow them short of hanging!

According to historians Adam J. Hirsch and David Rothman, the reform of this period was shaped less by intellectual movements in England than by a general clamor for action in a time of population growth and increasing social mobility, which prompted a critical reappraisal and revision of penal corrective techniques.

[81] Penal servitude, a mainstay of British and colonial American criminal justice, became nearly extinct during the seventeenth century, at the same time that Northern states, beginning with Vermont in 1777, began to abolish slavery.

[83] As the former American colonists expanded their political loyalty beyond the parochial to their new state governments, promoting a broader sense of the public welfare, banishment (or "warning out") also seemed inappropriate, since it merely passed criminals onto a neighboring community.

[145] By the eve of the American Civil War, Illinois, Indiana, Georgia, Missouri, Mississippi, Texas, and Arkansas, with varying success, had all inaugurated efforts to establish an Auburn-model prison in their jurisdictions.

[148] The penitentiary thus largely ended community involvement in the penal process—beyond a limited role in the criminal trial itself—though many prisons permitted visitors who paid a fee to view the inmates throughout the nineteenth century.

[160] The motives of these governors are not entirely unclear, historian Edward L. Ayers concludes: Perhaps they hoped that the additional patronage positions offered by a penitentiary would augment the historically weak power of the Southern executive; perhaps they were legitimately concerned with the problem of crime; or perhaps both considerations played a role.

But once established, southern penitentiaries took on lives of their own, with each state's system experiencing a complex history of innovation and stagnation, efficient and inefficient wardens, relative prosperity and poverty, fires, escapes, and legislative attacks; but they did follow a common trajectory.

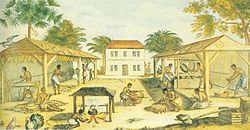

[206] Few immigrants or free blacks lived in the rural South in the pre-Civil War years,[209] and slaves remained under the dominant control of a separate criminal justice system administered by planters throughout the period.

At the same time, Reconstruction-era penology also focused on emerging "scientific" views of criminality related to race and heredity, as the post-war years witnessed the birth of a eugenics movement in the United States.

[227] Although these monitoring boards (established either by the state executive or legislature) would ostensibly ferret out abuses in the prison system, in the end their apathy toward the incarcerated population rendered them largely ill-equipped for task of ensuring even humane care, Rothman argues.

Fears about genetic contamination by the "criminal class" and its effect on the future of mankind led to numerous moral policing efforts aimed at curbing promiscuity, prostitution, and "white slavery" in this period.

[241] By October 1870, notable Reconstruction Era prison reformers Enoch Wines, Franklin Sanborn, Theodore Dwight, and Zebulon Brockway—among others—convened with the National Congress of Penitentiary and Reformatory Discipline in Cincinnati, Ohio.

[246] Christianson notes that the National Congress' membership generally subscribed to the prevailing contemporary notion that blacks and foreigners were disproportionately represented in the prison system due to their inherent depravity and social inferiority.

[246] The rise and decline of the Elmira Reformatory in New York during the latter part of the nineteenth century represents the most ambitious attempt in the Reconstruction Era to fulfill the goals set by the National Congress in the Declaration of Principles.

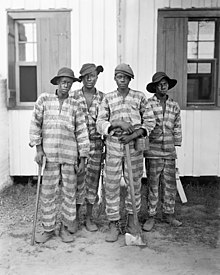

[257] By the end of Reconstruction, a new configuration of crime and punishment had emerged in the South: a hybrid, racialized form of incarceration at hard labor, with convicts leased to private businesses, that endured well into the twentieth century.

[261] Depressed economic conditions impacted both white and black farmers in the post-war South, as cotton prices entered a worldwide decline and interest rates on personal debt rose with "astonishing" speed after the close of hostilities.

"[275] As the Southern economy foundered in the wake of the peculiar institution's destruction, and property crime rose, state governments increasingly explored the economic potential of convict labor throughout the Reconstruction period and into the twentieth century.

[283] Texas also experienced a major postwar depression, in the midst of which its legislators enacted tough new laws calling for forced inmate labor within prison walls and at other works of public utility outside of the state's detention facilities.

[285] In cities like Savannah, Georgia, the Freedmen's Courts appeared even more disposed to enforcing the wishes of local whites, sentencing former slaves (and veterans of the Union Army) to chain gangs, corporal punishments, and public shaming.

[340] States began to cull the women, children, and the sick from the old privately run camps during this period, to remove them from the "contamination" of bad criminals and provide a healthier setting and labor regime.