History of catecholamine research

The catecholamines are a group of neurotransmitters composed of the endogenous substances dopamine, noradrenaline (norepinephrine), and adrenaline (epinephrine), as well as numerous artificially synthesized compounds such as isoprenaline - an anti-bradycardiac medication.

In the early 1890s, in the laboratory of Oswald Schmiedeberg in Strasbourg, the German pharmacologist Carl Jacob (1857–1944) studied the relationship between the adrenal glands and the intestine.

[6] While this may be true, Jacob did not envisage a chemical signal secreted into the blood to influence distant organs, the actual function of a hormone, but nerves running from the adrenals to the gut, "Hemmungsbahnen für die Darmbewegung".

George Oliver was a physician practicing in the spa town of Harrogate in North Yorkshire while Edward Albert Schäfer was Professor of Physiology at University College London.

He appears to have used his family in his experiments, and a young son was the subject of a series, in which Dr Oliver measured the diameter of the radial artery, and observed the effect upon it of injecting extracts of various animal glands under the skin.

… We may picture, then, Professor Schafer, in the old physiological laboratory at University College, … finishing an experiment of some kind, in which he was recording the arterial blood pressure of an anaesthetized dog.

… To him enters Dr Oliver, with the story of the experiments on his boy, and, in particular, with the statement that injection under the skin of a glycerin extract from calf's suprarenal gland was followed by a definite narrowing of the radial artery.

So Professor Schafer makes the injection, expecting a triumphant demonstration of nothing, and finds himself standing ′like some watcher of the skies, when a new planet swims into his ken,′ watching the mercury rise in the manometer with amazing rapidity and to an astounding height.Despite this tale being reiterated many times, it is not beyond doubt.

… I found that my visitor was Dr. George Oliver, [who] was desirous of discussing with me the results which he had been obtaining from the exhibition by the mouth of extracts from certain animal tissues, and the effects which these had in his hands produced upon the blood vessels of man."

[11] A 47-page account followed a year later, in the style of the time without statistics, but with precise description of many individual experiments and 25 recordings on kymograph smoked drums, showing, besides the blood pressure increase, reflex bradycardia and contraction of the spleen.

The material which they form and which is found, at least in its fully active condition, only in the medulla of the gland, produces striking physiological effects upon the muscular tissue generally, and especially upon that of the heart and arteries.

[22] The Japanese chemist Jōkichi Takamine, who had set up his own laboratory in New York, invented an isolation procedure and obtained it in pure crystal form in 1901,[23] and arranged for Parke-Davis to market it as "Adrenalin", spelt without the terminal "e".

In 1905 synthesis of the racemate was achieved by Friedrich Stolz at Hoechst AG in Höchst (Frankfurt am Main) and by Henry Drysdale Dakin at the University of Leeds.

I find that even after complete denervation, whether of three days' or ten months' duration, the plain muscle of the dilatator pupillae will respond to adrenalin, and that with greater rapidity and longer persistence than does the iris whose nervous relations are uninjured.

In a comprehensive structure-activity study of adrenaline-like compounds, Dale and the chemist George Barger in 1910 found that Elliott's hypothesis assumed a stricter parallelism between the effects of sympathetic nerve impulses and adrenaline than actually existed.

In a review of earlier work on catecholamine biosynthesis, German-British biochemist Hermann Blaschko (1900–1993) wrote: "Our modern knowledge of the biosynthetic pathway for the catecholamines begins in 1939, with the publication of a paper by Peter Holtz and his colleagues: they described the presence in the guinea-pig kidneys of an enzyme that they called dopa decarboxylase, because it catalyzed the formation of dopamine and carbon dioxide from the amino acid L-dopa.

[39][40] Edith Bülbring, who also had fled National Socialist racism in 1933, demonstrated methylation of noradrenaline to adrenaline in adrenal tissue in Oxford in 1949,[41] and Julius Axelrod detected phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase in Bethesda, Maryland in 1962.

This seemed to clarify the fate of the catecholamines in the body, but in 1956 Blaschko suggested that, because the oxidation was slow, "other mechanisms of inactivation … will be found to play an important part.

On April 16, 1945, Ulf von Euler of Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, who had already discovered or co-discovered substance P and prostaglandins, submitted to Nature the first of a series of papers that gave this proof.

They sought for catecholamines in human urine and found a blood pressure-increasing material Urosympathin that they identified as a mixture of dopamine, noradrenaline and adrenaline.

It is easy, of course, to be wise in the light of facts recently discovered; lacking them I failed to jump to the truth, and I can hardly claim credit for having crawled so near and then stopped short of it."

The present work is concerned with the question whether these sympathomimetic amines, besides their role as transmitters at vasomotor endings, play a part in the function of the central nervous tissue itself.

In this paper, these amines will be referred to as sympathin, since they were found invariably to occur together, with noradrenaline representing the major component, as is characteristic for the transmitter of the peripheral sympathetic system.

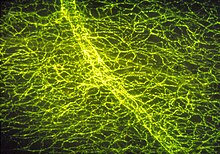

Her assignment was confirmed, the finishing touch being the visualization of the noradrenaline as well as adrenaline and (see below) dopamine pathways in the central nervous system by Annica Dahlström and Kjell Fuxe [sv] with the formaldehyde fluorescence method developed by Nils-Åke Hillarp (1916–1965) and Bengt Falck (born 1927) in Sweden and by immunochemistry techniques.

Transporters and intracellular enzymes such as monoamine oxidase operating in series constitute what the pharmacologist Ullrich Trendelenburg at the University of Würzburg called metabolizing systems.

Dale clearly saw the specificity of the "paralytic" (antagonist) effect of ergot for "the so-called myoneural junctions connected with the true sympathetic or thoracic-lumbar division of the autonomic nervous system"—the adrenoceptors.

Outstanding among them became isoprenaline, N-isopropyl-noradrenaline, of Boehringer Ingelheim, studied pharmacologically along with adrenaline and other N-substituted noradrenaline derivatives by Richard Rössler (1897–1945) and Heribert Konzett (1912–2004) in Vienna.

"Arrangement of all amines according to their bronchodilator effect yields a series from the most potent, isopropyl-adrenaline, via the approximately equipotent bodies adrenaline, propyl-adrenaline and butyl-adrenaline, to the weakly active isobutyl-adrenaline.

[88] Holtz erred in his interpretation, but Blaschko had "no doubt that his observations are of the greatest historical importance, as the first indication of an action of dopamine that characteristically and specifically differs from those of the two other catecholamines".

In 1986, the first gene coding for a catecholamine receptor, the β2-adrenoceptor from hamster lung, was cloned by a group of sixteen scientists, among them Robert Lefkowitz and Brian Kobilka of Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.