History of early Islamic Tunisia

He defeated another alliance of Berber forces near Tahirt (Algeria), then proceeded westward in a long series of military triumphs, eventually reaching the Atlantic coast, where he is said to have lamented that before him lay no more lands to conquer for Islam.

Yet Zuhair b. Qais, the deputy of the fallen leader Uqba ibn Nafi, enlisted Zanata Berber tribes from Cyrenaica to fight for the cause of Islam, and in 686 managed to overrun, defeat, and terminate the kingdom newly formed by Kusaila.

[10] The Berbers, however, continued to offer stiff resistance, then being led by a woman of the Jarawa tribe, whom the Muslims called "the prophetess" [al-Kahina in Arabic]; her actual name was approximately Damiya.

Some commentators speculate that, to the Kahina Damiya, the invading Arabs appeared primarily interested in booty, because she then commenced to sack and pillage the region, apparently to make it unattractive to raiders looking for the spoils of war; of course, it also made her own forces hotly unpopular to local inhabitants.

Muslim ships fitted for war began to assert dominance over the adjacent Mediterranean coast; hence the Byzantines then made their final withdrawal from North Africa.

By choosing to ally not with nearby Europe, familiar in memory by the Roman past,[30] but rather with the newcomers from distant Arabia, the Berbers knowingly decided their future and historical path.

[32][33][34] Perhaps this linguistic kinship shares a further resonance, e.g., in mythic explanations, popular symbols, and religious preference,[35][36][37] in some vital fundamentals of psychology,[38][39] and in the media of culture and the context of tradition.

[50] Also inducing the Berbers to convert was the early lack of rigor in religious obligations, as well as the prospect of inclusion as warriors in the armies of conquest, with a corresponding share in booty and tribute.

[52][53] To locate its history of religion context, the Arab conquest and the Islamic conversion of the Berbers followed a centuries-long period of religious conflict and polarization of society in the old Roman Empire's Africa Province.

Here, the Donatist schism within Christianity proved instrumental; it caused divisions in society, often between the rural Berbers, who were prominent in schismatic dissent, and the more urban orthodoxy of the Roman church.

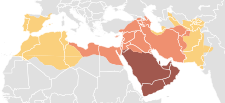

[58][59][60] After the conquest and following the popular conversion, Ifriqiya constituted a proximous and natural focus for an Arab-Berber Islamic regime in North Africa, a center for culture and society.

During the years immediately preceding the fall of the Umayyad Caliphate of Damascus (661-750),[61] revolts arose among the Kharijite Berbers in Morocco which eventually disrupted the stability of the entire Maghrib (739-772).

Disregarding the strong religious sentiments held by many in the emerging Muslim community, the Aghlabids often led lives of pleasure at variance to Islamic law, e.g., publicly drinking wine.

In its final decline, however, the dynasty self-destructed, in that its eleventh and last amir, Ziyadat Allah III (r. 902-909) (d. 916), due to insecurity stemming from his father's assassination, ordered his rival brothers and uncles executed.

"[82] On the other hand, the administrative staffs were composed of dependent clients (mostly recent Arab and Persian immigrants), and the local bilingual Afariq (mostly Berber, and which included many Christians).

[83] Aghlabid offices included the vizier [prime minister], the hajib [chamberlain], the sahib al-barid [master of posts and intelligence], and numerous kuttab [secretaries] (e.g., of taxation, of the mint, of the army, of correspondence).

The influential law book called Mudawanna, written by his disciple Sahnun ('Abd al-Salam b. Sa'id) (776-854), provided a "vulgate of North-African Malikism" for practical use during the period when Maliki legal doctrines won the field against its rival, the Hanafi.

[91] The Maliki jurists were often at odds with the Aghlabids, over the Arab rulers' disappointing personal moral conduct, and over the fiscal issue of taxation of agriculture (i.e., of a new fixed cash levy replacing the orthodox tithe in kind).

[67] Further, the Maliki fuqaha was commonly understood to act more in favor of local autonomy, hence in the interests of the Berbers, by blocking potential intrusions into Ifriqiya affairs and filtering out foreign influence, which might originate from the central Arab power in the East.

By virtue of their piety and independence, the ābid won social prestige and a voice in politics; some scholars would speak on behalf of the governed cities, criticizing the regime's finance and trade decisions.

[93] Although substantially different, the status of the ābid relates somewhat to the much later, largely Berber figure of the Maghribi saint, the wali, who as keeper of baraka (spiritual charisma) became the object of veneration by religious believers, and whose tomb would be the destination of pilgrimage.

Extensive improvements were made to the pre-existing water works in order to promote olive groves and other agriculture (oils and cereals were exported), to irrigate the royal gardens, and for livestock.

Also, improved trade routes linked Ifriqiya with the continental interior, the Sahara and the Sudan, regions regularly incorporated into the Mediterranean commerce for the first time during this period.

[102] A prosperous economy permitted a refined and luxurious court life and the construction of the new palace cities of al-'Abbasiya (809), and Raqada (877), where were situated the new residences of the ruling emir.

[103][104][105] The origins of the Rustamid state can be traced to the Berber Kharijite (Ar: Khawarij) revolt (739-772) against the new Arab Sunni power that was being established across North Africa following the Islamic conquest.

Never attaining lasting success, but persisting in its struggles, the Kharijite movement remains today only in its Ibadi branch, with small minorities in isolated locales throughout the Muslim world.

[109] Apart from the lands surrounding Tahert, Rustamid territory consisted of largely the upland steppe or "pre-Sahara" that forms the frontier between the better watered coastal regions of the Maghrib and the arid Sahara desert.

Instead the communities of the pre-desert wadis and Jebel ranges may have been absorbed in a larger tribal confederation variously labeled the Laguatan, Levathae or, in the Arabic sources, the Lawata.

Indeed Savage suggests that many of the 'tribal' groups which figure in the sources in this period, notably the Nefusa, may represent alliances of disparate communities which coalesced at this very time in response to the catalyst provided by the egalitarian Ibadi message and were retrospectively legitimized with a genealogical tribal framework.

"[133] This al-Mu'izz was highly educated, wrote Arabic poetry, had mastered Berber, studied Greek, and delighted in literature; he was also a very capable ruler and it was he who founded Fatimid power in Egypt.