Isabeau of Bavaria

[4] As part of his duties as a member of the regency council that governed France during the minority of Charles VI, the king's uncle, Philip the Bold, thought that the proposed marriage to Isabeau would be an ideal means to build an alliance with the Holy Roman Empire in opposition to the crown of England.

[5] Isabeau's father reluctantly agreed to the plan and sent her to France with his brother Frederick on the pretext of taking a pilgrimage to Amiens, whose Cathedral housed a celebrated relic of the time (the reputed head of John the Baptist).

[3] Before her presentation to Charles, Isabeau visited Hainaut for about a month, staying with her granduncle Duke Albert I, Count of Holland, who also ruled part of the hereditary Wittelsbach territories of Bavaria-Straubing.

Arrangements were made for the two to be married in Arras, but on the first meeting, Charles felt "happiness and love enter his heart, for he saw that she was beautiful and young, and thus he greatly desired to gaze at her and possess her".

On the occasion of their first New Year in 1386, he gave her a red velvet palfrey saddle trimmed with copper and decorated with an intertwined K and E (for Karol and Elisabeth), and he continued to give her gifts of rings, tableware and clothing.

The day after the wedding, Charles departed for a military campaign against the English, whereas Isabeau traveled to Creil to live with his step-great-grandmother, Queen Dowager Blanche, who taught her courtly traditions.

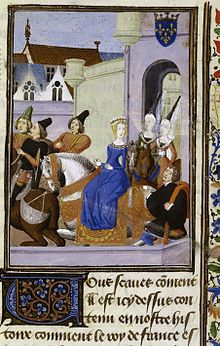

The procession began at the Porte de St. Denis and passed under a canopy of sky-blue cloth beneath which children dressed as angels sang, winding into the Rue Saint-Denis before arriving at the Notre Dame for the coronation ceremony.

"[11] As Isabeau crossed the Grand Pont to Notre Dame, a person dressed as an angel descended from the church by mechanical means and "passed through an opening of the hangings of blue taffeta with golden fleurs-des-lis, which covered the bridge, and put a crown on her head."

[10] In 1392, Charles suffered the first of what was to become a lifelong series of bouts of insanity when, on a hot August day outside Le Mans, he attacked his retinue, including his brother Orléans, killing four men.

"[22] Since the King often did not recognize her during his psychotic episodes and was upset by her presence, it was eventually deemed advisable to provide him with a mistress, Odette de Champdivers, the daughter of a horse-dealer.

Historian Tracy Adams writes that Isabeau's attachment and loyalty is evident in the great efforts she made to retain the crown for his heirs in the ensuing decades.

[26] Isabeau's movements and political activities are well documented after the time of her marriage, partially because of the unusual positions of power she occupied as a result of her husband's recurring illnesses.

Some years later, however, at the 1396 wedding of her seven-year-old daughter Isabella to Richard II of England, Isabeau successfully negotiated an alliance between France and Florence with the Florentine ambassador Buonaccorso Pitti.

[27] During his short-lived recovery in the 1390s, Charles made arrangements for Isabeau to be "principal guardian of the Dauphin", their son, until he reached 13 years of age, giving her additional political power on the regency council.

[20] Charles appointed Isabeau co-guardian of their children in 1393, a position shared with the royal dukes and her brother, Louis of Bavaria, while he gave Orléans full power of the regency.

[29] The following year, as Charles' bouts of illness became more severe and prolonged, Isabeau became the leader of the regency council, giving her power over the royal dukes and the Constable of France, while at the same time making her vulnerable to attack from various court factions.

[25] In 1401, during one of the King's absences, Orléans installed his own men to collect royal revenues, angering Philip the Bold who in retaliation raised an army, threatening to enter Paris with 600 men-at-arms and 60 knights.

Whether the two were intimate has been questioned by contemporary historians, including Gibbons who believes the rumor may have been planted as propaganda against Isabeau as retaliation against tax increases she and Orléans ordered in 1405.

[7][25] An Augustinian friar, Jacques Legrand (writer) [fr; de], preached a long sermon to the court denouncing excess and depravity, in particular mentioning Isabeau and her habit of wearing clothing with exposed necks, shoulders and décolletage.

[38] On 23 November,[39] hired killers attacked the duke as he returned to his Paris residence, cut off his hand holding the horse's reins, and "hacked [him] to death with swords, axes, and wooden clubs".

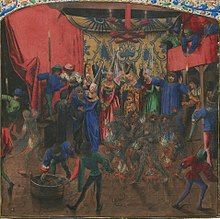

[42] Petit argued convincingly that in the King's absence Orléans had become a tyrant,[43] practiced sorcery and necromancy, was driven by greed, and had planned to commit fratricide at the Bal des Ardents.

John gained the upper hand during the first year, but the Dauphin began to build a power base; Christine de Pizan wrote of him that he was the savior of France.

At that time, Armagnac imprisoned Isabeau in Tours, confiscating her personal property (clothing, jewels and money), dismantling her household, and separating her from the younger children as well as her ladies-in-waiting.

[53] According to Tuchman, Isabeau had a farmhouse built in St. Ouen where she looked after livestock, and in her later years, during a lucid episode, Charles arrested one of her lovers whom he tortured, then drowned in the Seine.

Furthermore, Adams admits she believed the allegations against Isabeau until she delved into contemporary chronicles: there she found little evidence against the Queen except that many of the rumors came from only a few passages, and in particular from Pintoin's pro-Burgundian writing.

[67] Pintoin said of the Queen and Orléans that they neglected Charles, behaved scandalously and "lived on the delights of the flesh",[68] spending large amounts of money on court entertainment.

[69] Isabeau was accused of indulging in extravagant and expensive fashions, jewel-laden dresses and elaborate braided hairstyles coiled into tall shells, covered with wide double hennins that, reportedly, required widened doorways to pass through.

[33] She was accused of leading France into a civil war because of her inability to support a single faction; she was described as an "empty headed" German; of her children, it was said that she "took pleasure in a new pregnancy only insofar as it offered her new gifts"; and her political mistakes were attributed to her being fat.

[note 7] Contemporary documents identify the statuette as a New Year's gift—an étrennes—a Roman custom Charles revived to establish rank and alliances during the period of factionalism and war.

In 1402, she sent a compilation of her literary argument Querelle du Roman de la Rose—in which she questions the concept of courtly love—with a letter exclaiming "I am firmly convinced the feminine cause is worthy of defense.