History of nuclear fusion

[1][2] Quantum tunneling was discovered by Friedrich Hund in 1929, and shortly afterwards Robert Atkinson and Fritz Houtermans used the measured masses of light elements to show that large amounts of energy could be released by fusing small nuclei.

A theory verified by Hans Bethe in 1939 showed that beta decay and quantum tunneling in the Sun's core might convert one of the protons into a neutron and thereby produce deuterium rather than a diproton.

Lyman Spitzer began considering ways to solve problems involved in confining a hot plasma, and, unaware of the Z-pinch efforts, he created the stellarator.

The AEC had issued more realistic testimony regarding fission to Congress months before, projecting that "costs can be brought down... [to]... about the same as the cost of electricity from conventional sources..."[22] In 1951 Edward Teller and Stanislaw Ulam at Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) developed the Teller-Ulam design for a thermonuclear weapon, allowing for the development of multi-megaton yield fusion bombs.

Attendees remember him saying in effect that the fields were like rubber bands, and they would attempt to snap back to a straight configuration whenever the power was increased, ejecting the plasma.

The current made magnetic fields that pinched the plasma, raising temperatures to 15 million degrees Celsius, for long enough that atoms fused and produced neutrons.

[38] Plasma temperatures of approximately 40 million degrees Celsius and 109 deuteron-deuteron fusion reactions per discharge were achieved at LANL with Scylla IV.

With an apparent solution to the magnetic bottle problem in-hand, plans begin for a larger machine to test scaling and methods to heat the plasma.

[41] The "advanced tokamak" concept emerged, which included non-circular plasma, internal diverters and limiters, superconducting magnets, and operation in the so-called "H-mode" island of increased stability.

[47] The Princeton Large Torus (PLT), the follow-on to the Symmetrical Tokamak, surpassed the best Soviet machines and set temperature records that were above what was needed for a commercial reactor.

The DOE selected a Princeton design Tokamak Fusion Test Reactor (TFTR) and the challenge of running on deuterium-tritium fuel.

What was once a series of individual rings passing through the hole in the center of the reactor was reduced to a single post, allowing for aspect ratios as low as 1.2.

Robinson gathered a team and secured on the order of 100,000 pounds to build an experimental machine, the Small Tight Aspect Ratio Tokamak, or START.

Parts of the machine were recycled from earlier projects, while others were loaned from other labs, including a 40 keV neutral beam injector from ORNL.

Through this work and lobbying by groups like the fusion power associates and John Sethian at NRL, Congress authorized funding for the NIF project in the late nineties.

[73][74] In response, Todd Rider at MIT developed general models of these devices,[75] arguing that all plasma systems at thermodynamic equilibrium were fundamentally limited.

In 1995, William Nevins published a criticism[76] arguing that the particles inside fusors and polywells would acquire angular momentum, causing the dense core to degrade.

[80][81] The next year, Tore Supra reached a record plasma duration of two minutes with a current of almost 1 M amperes driven non-inductively by 2.3 MW of lower hybrid frequency waves (i.e. 280 MJ of injected and extracted energy), enabled by actively cooled plasma-facing components.

In the late nineties, a team at Columbia University and MIT developed the levitated dipole,[89] a fusion device that consisted of a superconducting electromagnet, floating in a saucer shaped vacuum chamber.

In April 2005, a UCLA team announced[98] a way of producing fusion using a machine that "fits on a lab bench", using lithium tantalate to generate enough voltage to fuse deuterium.

[113] In August 2014, Phoenix Nuclear Labs announced the sale of a high-yield neutron generator that could sustain 5×1011 deuterium fusion reactions per second over a 24-hour period.

[121] In 2018, Eni announced a $50 million investment in Commonwealth Fusion Systems, to attempt to commercialize ARC technology using a test reactor (SPARC) in collaboration with MIT.

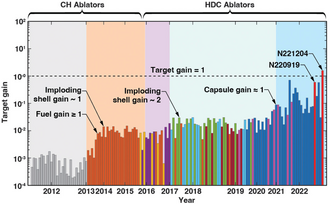

[126] In 2010, NIF researchers conducted a series of "tuning" shots to determine the optimal target design and laser parameters for high-energy ignition experiments with fusion fuel.

[138] In 2017 the reactor achieved a stable 101.2-second steady-state high confinement plasma, setting a world record in long-pulse H-mode operation.

[139] In 2018 MIT scientists formulated a theoretical means to remove the excess heat from compact nuclear fusion reactors via larger and longer divertors.

[140] In 2019 the United Kingdom announced a planned £200-million (US$248-million) investment to produce a design for a fusion facility named the Spherical Tokamak for Energy Production (STEP), by the early 2040s.

[146] In 2020, Chevron Corporation announced an investment in start-up Zap Energy, co-founded by British entrepreneur and investor, Benj Conway, together with physicists Brian Nelson and Uri Shumlak from University of Washington.

[citation needed] In August 2021, the National Ignition Facility recorded a record-breaking 1.3 megajoules of energy created from fusion which is the first example of the Lawson criterion being surpassed in a laboratory.

[160] In October 2022, the Korea Superconducting Tokamak Advanced Research (KSTAR) reached a record plasma duration of 45 seconds,[161] sustaining the high-temperature fusion plasma over the 100 million degrees Celsus based on the integrated real-time RMP control for ELM-less H-mode, i.e. fast ions regulated enhancement (FIRE) mode,[162][163] machine learning algorithm, and 3D field optimization via an edge-localized RMP.

KSTAR also set a record (shot #34445) for the longest steady-state duration at a temperature of 100 million degrees Celsius (48 seconds, ELM-LESS FIRE mode).