National Ignition Facility

In 2021, after improvements in fuel target design, NIF produced 70% of the energy of the laser, beating the record set in 1997 by the JET reactor at 67% and achieving a burning plasma.

[13] Inertial confinement fusion (ICF) devices use intense energy to rapidly heat the outer layers of a target in order to compress it.

[16] The target is a small spherical pellet containing a few milligrams of fusion fuel, typically a mix of deuterium (D) and tritium (T), as this composition has the lowest ignition temperature.

In the indirect drive case, the cylinder, called a hohlraum (German for 'hollow room' or 'cavity'), becomes hot enough to re-emit the energy as even higher frequency X-rays.

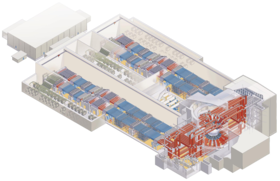

[33] As of 2010 NIF aimed to create a single 500 terawatt (TW) peak flash of light that reaches the target from numerous directions within a few picoseconds.

This starts with a low-power flash of 1053-nanometer (nm) infrared light generated in an ytterbium-doped optical fiber laser termed Master Oscillator.

The second stage sends the light four times through a circuit containing a neodymium glass amplifier similar to (but much smaller than) the ones used in the main beamlines, boosting the millijoules to about 6 joules.

Since the path length from the Master Oscillator to the target is different for each beamline, optics are used to delay the light in order to ensure that they all reach the center within a few picoseconds of each other.

The power delivered by NIF UV rays was estimated to be more than enough to cause ignition, allowing fusion energy gains of about 40x, somewhat higher than the indirect drive system.

The DT fuel would be placed in a small capsule, designed to rapidly ablate when heated and thereby maximize compression and shock wave formation.

During the construction phase, Nuckolls found an error in his calculations, and an October 1979 review chaired by former LLNL director John S. Foster Jr. confirmed that Nova would not reach ignition.

The Department of Energy (DOE) decided that direct experimentation was the best way to settle the issue, and in 1978 they started a series of underground experiments at the Nevada Test Site that used small nuclear bombs to illuminate ICF targets.

[59] During this same period, experiments began on Nova using similar targets to understand their behavior under laser illumination, allowing direct comparison against the bomb tests.

[69] At the same time, the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) was signed in 1996, which would ban all criticality testing and made the development of newer generations of nuclear weapons more difficult.

Out of these changes came the Stockpile Stewardship and Management Program (SSMP), which, among other things, included funds for the development of methods to design and build nuclear weapons without having to test them explosively.

[72] A retired Sandia manager, Bob Puerifoy, was even more blunt than Spielman: "NIF is worthless ... it can't be used to maintain the stockpile, period".

[83] In November 1997, an El Niño storm dumped two inches of rain in two hours, flooding the NIF site with 200,000 gallons of water just three days before the scheduled foundation pour.

[86] Sandia, with extensive experience in pulsed power delivery, designed the capacitor banks used to feed the flashlamps, completing the first unit in October 1998.

[57] Continuing problems further delayed operations, and in September 1999, an updated DOE report stated that NIF required up to $350 million more and completion occur only in 2006.

[81][89] The report noted management problems for the overruns, and criticized the program for failing to budget money for target fabrication, including it in operational costs instead of development.

John Gordon, National Nuclear Security Administrator, stated "We have prepared a detailed bottom-up cost and schedule to complete the NIF project...

[91][92] A follow-up report the next year pushed the budget to $4.2 billion, and the completion date to 2008.The project got a new management team[93][94] in September 1999, headed by George Miller, who was named acting associate director for lasers.

Ed Moses, former head of the Atomic Vapor Laser Isotope Separation (AVLIS) program at LLNL, became NIF project manager.

[96] In 2005, an independent review by the JASON Defense Advisory Group that was generally positive, concluded that "The scientific and technical challenges in such a complex activity suggest that success in the early attempts at ignition in 2010, while possible, is unlikely".

[100] On March 10, 2009, NIF became the first laser to break the megajoule barrier, delivering 1.1 MJ of UV light, known as 3ω (from third-harmonic generation), to the target chamber center in a shaped ignition pulse.

[105] Plasma Physics Group Leader Siegfried Glenzer said that they could maintain the precise fuel layers needed in the lab, but not yet within the laser system.

Then minute amounts of water vapor appeared in the target chamber and froze to the windows on the ends of the hohlraums, causing an asymmetric implosion.

[117][118] In 2008, LLNL began the Laser Inertial Fusion Energy program (LIFE), to explore ways to use NIF technologies as the basis for a commercial power plant design.

[126] On January 28, 2016, NIF successfully executed its first gas pipe experiment intended to study the absorption of large amounts of laser light within 1 centimetre (0.39 in) long targets relevant to high-gain magnetized liner inertial fusion (MagLIF).

[146][147][144] Some similar experimental ICF projects are: The NIF was used as the set for the starship Enterprise's warp core in the 2013 movie Star Trek Into Darkness.