History of slavery in Virginia

Colonial Virginia became an amalgamation of Algonquin-speaking Native Americans, English, other Europeans, and West Africans, each bringing their own language, customs, and rituals.

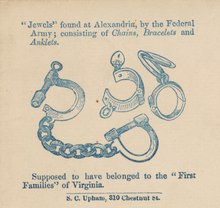

For more than 200 years, enslaved people had to deal with a wide range of horrors, such as physical abuse, rape, being separated from family members, lack of food, and degradation.

The worst difficulty was being separated from family members when they were sold; consequently, they developed coping mechanisms, such as passive resistance, and creating work songs to endure the harsh days in the fields.

[12] By 1620, there were 32 Africans and four Native Americans in the "Others not Christians in the Service of the English" category of the muster who arrived in Virginia, but that number was reduced by 1624, perhaps due to the Second Anglo-Powhatan War (1622–1632) or illness.

In 1628, a slave ship carried 100 people from Angola to be sold into slavery in Virginia, and consequently the number of Africans in the colony rose greatly.

[22] They exchanged their labor for the cost of their passage to the colony, room and board, and freedom dues, which were stipulated to be provided to the servant at the end of the indenture period, and could include land and supplies that would help them become established on their own.

[27] Domestic work, another duty, included preparing and serving food, cleaning, and caretaking of white children; others were trained to be blacksmiths, carpenters, and coopers.

Servants, differentiated from slaves, had rights to safety, the receipt of food and goods at the end of their term of service, and to resolve legal issues first with a justice of the peace, then in court, if needed.

"[43] Tobacco farming in eastern Virginia so depleted the fertility of its soil that by 1800, farmers began to look to the west for good land to raise crops.

The area was settled by German and Scotch-Irish people, who had little need for or interest in slavery, and the absence of competition with unpaid slave labor prevented the development of class divisions like those in the east.

African Americans developed cultural traditions that helped them cope with being enslaved, supported family members and friends, and promoted their human dignity.

Either way, religious practices—such as music, call-and-response forms of worship, and funeral customs—helped blacks preserve their African traditions and manage "the dehumanizing effects of slavery and segregation".

They sang communal songs called spirituals about deliverance, salvation, and resistance[27] Music was an important part of the social fabric of African American communities.

[27][57] At hog butchering time, the best cuts of meat were kept for the master's household and the remainder, such as fatback, snouts, ears, neck bones, feet, and intestines (chitterlings) were given to the slaves.

[58] Enslaved adults were typically given a peck (9 liters) of cornmeal and 3–4 pounds (1.5–2 kilos) of pork per week, and from those rations come soul food staples such as cornbread, fried catfish, chitterlings, and neckbones.

[57][61] Similarly to the ways in which early Virginians shared knowledge and traditions of their heritage with one another,[62] enslaved people prepared meals based upon European, indigenous, and African cuisines, devising their own cookery from the limited rations given to them by their masters.

[63] The Atlantic slave trade started in the sixteenth century when Portuguese and Spanish ships transported enslaved people to South America, and then to the West Indies.

‘Run away from his Master Philip Reynolds of James River Virginia, and suppos’d to have come over into England, a ... Man, nam'd Scipio, (but now calls himself John Whitt) He is a short Fellow, Coal Black, and round faced; aged about 24 Years; he hath a Hole through his left Ear, and a Sort of a Star between his Shoulders on his Back; he work’d there as a Glazier and a Tinker, and plays on the Violin.

[75] John Whitt and his companion took advantage of their environment and contacts to make good their escape, disappearing quietly along the James River and into the crowds of the busy dockyards of the Virginian coastline.

After Nat Turner's rebellion, thousands of Virginians sent the legislature over forty petitions calling for an end to slavery, and Richmond's newspapers argued fiercely for abolition.

[80][81] According to historian Eva Sheppard Wolf, "The response of white Virginians continued well beyond their initial fit of violence and included the most public, focused, and sustained discussion of slavery and emancipation that occurred in the commonwealth or any other southern state.

The 1782 laws also permitted masters to free their slaves of their own accord; previously, a manumission had required obtaining consent from the state legislature, which was arduous and rarely granted.

[107] Slaves from Virginia escaped via waterways and overland to free states in the North, some being aided by people who lived along the Underground Railroad, which was maintained by both whites and blacks.

[107] In 1849, slave Henry "Box" Brown escaped from slavery in Virginia when he arranged to be shipped by express mail in a crate to Philadelphia,[106] arriving in little more than 24 hours.

[92] White residents of Virginia found freed blacks to be a "great inconvenience" and were suspicious of their ability to influence enslaved people and accused them of crimes.

Evidence "suggests that black education in Virginia, as elsewhere in the South, was a product of the freed people's own initiative and determination, temporarily supported by northern benevolence and federal aid.

Henry Louis Gates Jr. cites a quote by Ira Berlin of a common saying at the time: "even the lowest whites [could] threaten free Negroes … with 'a good nigger beating.

Constant Hanks, a private in the New York State Militia, wrote in a letter to his father after the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect on January 1, 1863: "Thank God... the contest is now between Slavery & Freedom, & every honest man knows what he is fighting for.

"[137][138] Booker T. Washington, born enslaved on the Burroughs plantation in Franklin County, Virginia, later described the food shortages that resulted from the Union blockades during the Civil War and how it affected the owners much more than it did the slaves.

[135] Slave trading continued until the defeat of the Confederacy, but the economic uncertainty wrought by the conflict had a negative impact that was immediately visible in Richmond, according to one 1861 newspaper report:[140] Business of every kind, not necessarily connected with the war, is entirely Prostrated.