History of syphilis

[2] Many well-known figures, including Scott Joplin, Franz Schubert, Friedrich Nietzsche, Al Capone, and Édouard Manet are believed to have contracted the disease.

This epidemic, perhaps the result of a more transmissible or deadlier variant of treponematosis, although that is not yet known, led to significant confusion beginning in the eighteenth century and exemplified most recently in the work of Kristin N. Harper and colleagues.

[19][20][13][21] In 2020, a group of leading paleopathologists concluded that enough evidence had been collected from bones and teeth to prove that treponemal disease existed in Europe prior to the voyages of Columbus.

[18] As syphilis, bejel, and yaws vary considerably in mortality rates and the level of human disgust they elicit, it is important to know which one is under discussion in any given case, but it remains difficult for paleopathologists to distinguish among them.

[31] The genetic sequence of Treponema pallidum was deciphered by Claire M. Fraser and colleagues in 1998, and success in analyzing a 200-year-old example extracted from bones by Connie J. Kolman et al. came the next year.

[32][33] In 2012, Rafael Montiel and his co-authors were successful in amplifying two Treponema pallidum DNA sequences dated to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in southwestern Spain.

[34] In 2018 Verena J. Schuenemann and colleagues successfully recovered and reconstructed Treponema pallidum genomes from the skeletons of two infants and a neonate in Mexico City, from the late 17th to the mid-19th centuries.

[35] A breakthrough example (2020) from early modern Europe can be found in the work of Karen Giffin and her co-authors, who sequenced a genome of Treponema pallidum subspecies pertenue, the causal agent of yaws, from a Lithuanian tooth radiocarbon-dated to 1447–1616 (95 percent probability).

Research by Marylynn Salmon has provided examples of deformities in medieval subjects that can be usefully compared to those of modern victims of the disease in medical drawings and photographs.

The association of saddle nose with men perceived to be so evil they would kill the son of God indicates the artists were thinking of syphilis, which is typically transmitted through sexual intercourse with promiscuous partners.

[citation needed] It remains mysterious why the authors of medieval medical treatises so uniformly refrained from describing syphilis or commenting on its existence in the population.

In France, the association of syphilis with court life was responsible for the term mal de cour, which usage lasted into modern times.

[43][44][45][46] The fact that following the epidemic of 1495 countries blamed its rapid transmission on each other (in Naples it was called the French Pox and in France the Neapolitan disease) indicates that syphilis was immediately perceived negatively.

"[47] However, Crosby considers it more likely that a highly contagious ancestral species of the bacteria moved with early human ancestors across the land bridge of the Bering Straits many thousands of years ago without dying out in the original source population.

Upon arrival in the Old World, the bacterium, which was similar to modern day yaws, responded to new selective pressures with the eventual birth of the subspecies of sexually transmitted syphilis.

As Jared Diamond describes it, "[W]hen syphilis was first definitely recorded in Europe in 1495, its pustules often covered the body from the head to the knees, caused flesh to fall from people's faces, and led to death within a few months."

Many of the crew members who served on this voyage later joined the army of King Charles VIII in his invasion of Italy in 1495, which some argue may have resulted in the spreading of the disease across Europe and as many as five million deaths.

[11] Some findings suggest Europeans could have carried the nonvenereal tropical bacteria home, where the organisms may have mutated into a more deadly form in the different conditions and low immunity of the population of Europe.

The inherent xenophobia of the terms also stemmed from the disease's particular epidemiology, often being spread by foreign sailors and soldiers during their frequent sexual contact with local prostitutes.

The aim of treatment was to expel the foreign, disease-causing substance from the body, so methods included blood-letting, laxative use, and baths in wine and herbs or olive oil.

[67] Paracelsus likewise noted mercury's positive effects in the Arabic treatment of leprosy, which was thought to be related to syphilis, and used the substance for treating the disease.

An antimicrobial used for treating disease was the organo-arsenical drug Salvarsan, whose anti-syphility properties were discovered in 1908 by Sahachiro Hata in the laboratory of Nobel Prize winner Paul Ehrlich.

[79] These treatments were finally rendered obsolete by the discovery of penicillin, and its widespread manufacture after World War II allowed syphilis to be effectively and reliably cured.

[83] An excavation of a seventeenth-century cemetery at St Thomas's Hospital in London, England found that 13 per cent of skeletons showed evidence of treponemal lesions.

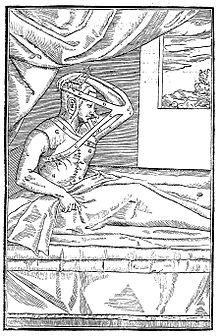

[89] The earliest known depiction of an individual with syphilis is Albrecht Dürer's Syphilitic Man (1496), a woodcut believed to represent a Landsknecht, a Northern European mercenary.

[91] The myth of the femme fatale or "poison women" of the 19th century is believed to be partly derived from the devastation of syphilis, with classic examples in literature including John Keats' La Belle Dame sans Merci.

That the artist chose to include this image in a series of works celebrating the New World indicates how important a treatment, however ineffective, for syphilis was to the European elite at that time.

[99] In the 1960s, Peter Buxtun sent a letter to the CDC, who controlled the study, expressing concern about the ethics of letting hundreds of black men die of a disease that could be cured.

As a result, the program was terminated, a lawsuit brought those affected nine million dollars, and Congress created a commission empowered to write regulations to deter such abuses from occurring in the future.

Doctors infected soldiers, prisoners, and mental patients with syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases, without the informed consent of the subjects, and then treated them with antibiotics.