Ignaz Semmelweis

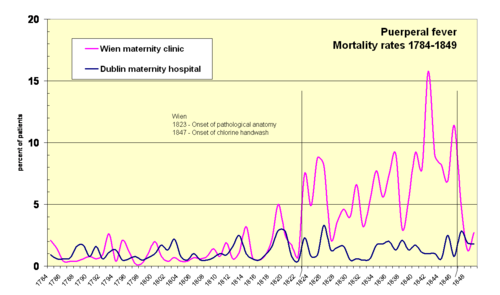

Semmelweis discovered that the incidence of infection could be drastically reduced by requiring healthcare workers in obstetrical clinics to disinfect their hands.

He could offer no theoretical explanation for his findings of reduced mortality due to hand-washing, and some doctors were offended at the suggestion that they should wash their hands and mocked him for it.

József Semmelweis was granted citizenship in Buda in 1806 and, in the same year, he opened a wholesale business for spices and general consumer goods.

[B] The company was named Zum weißen Elefanten (At the White Elephant) in the Meindl House (today's Semmelweis Museum of Medical History, located at 1–3 Apród Street, Budapest).

Semmelweis was puzzled that puerperal fever was rare among women giving street births, prompting his curiosity as to what protected those who delivered outside the clinic.

[16] Semmelweis' breakthrough occurred in 1847, following the death of his good friend Jakob Kolletschka, who had been accidentally poked with a student's scalpel while performing a post mortem examination.

He did this because he found that this chlorinated solution worked best to remove the putrid smell of infected autopsy tissue, and thus perhaps destroyed the causal "poisonous" or contaminating "cadaveric" agent hypothetically being transmitted by this material.

Semmelweis was outraged by the indifference of the medical profession and began writing open and increasingly angry letters to prominent European obstetricians, at times denouncing them as irresponsible murderers.

His contemporaries, including his wife, believed he was losing his mind, and in 1865, nearly 20 years after his breakthrough, he was committed to the Landesirrenanstalt Döbling (provincial lunatic asylum).

The findings from autopsies of deceased women also showed a confusing multitude of physical signs, which emphasized the belief that puerperal fever was not one, but many different, yet unidentified, diseases.

Also, some historians of science[19] argue that resistance to path-breaking contributions of obscure scientists is common and "constitutes the single most formidable block to scientific advances."

During 1848, Semmelweis widened the scope of his washing protocol, to include all instruments coming in contact with patients in labour, and used mortality rates time series to document his success in virtually eliminating puerperal fever from the hospital ward.

Hebra claimed that Semmelweis's work had a practical significance comparable to that of Edward Jenner's introduction of cowpox inoculations to prevent smallpox.

[25] As accounts of the dramatic reduction in mortality rates in Vienna were being circulated throughout Europe, Semmelweis had reason to expect that the chlorine washings would be widely adopted, saving tens of thousands of lives.

[29] Some accounts emphasize that Semmelweis refused to communicate his method officially to the learned circles of Vienna,[30] nor was he eager to explain it on paper.

Two days later in Hungary, demonstrations and uprisings led to the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 and a full-scale war against the ruling Habsburgs of the Austrian Empire.

Semmelweis's superior, professor Johann Klein, was a conservative Austrian, likely uneasy with the independence movements and alarmed by the other revolutions of 1848 in the Habsburg areas.

[33] Semmelweis's application for an extension was supported by Joseph Škoda and Carl von Rokitansky and by most of the medical faculty, but Klein chose Braun for the position.

[37] During 1848–1849, some 70,000 troops from the Habsburg-ruled Austrian Empire thwarted the Hungarian independence movement, executed or imprisoned its leaders and in the process destroyed parts of Pest.

[38] Childbed fever was rampant at the clinic; at a visit in 1850, just after returning to Pest, Semmelweis found one fresh corpse, another patient in severe agony, and four others seriously ill with the disease.

A typical example was W. Tyler Smith, who claimed that Semmelweis "made out very conclusively" that "miasms derived from the dissecting room will excite puerperal disease.

[44] In 1856, Semmelweis's assistant Josef Fleischer reported the successful results of hand washing activities at St. Rochus and Pest maternity institutions in the Viennese Medical Weekly (Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift).

Other supposed causes included conception and pregnancy, uremia, pressure exerted on adjacent organs by the shrinking uterus, emotional traumata, mistakes in diet, chilling, and atmospheric epidemic influences.

Breisky objected that Semmelweis had not proved that puerperal fever and pyemia are identical, and he insisted that other factors beyond decaying organic matter certainly had to be included in the etiology of the disease.

[54] Carl Edvard Marius Levy, head of the Copenhagen maternity hospital and an outspoken critic of Semmelweis's ideas, had reservations concerning the unspecific nature of cadaverous particles and that the supposed quantities were unreasonably small.

[56] It has been contended that Semmelweis could have had an even greater impact if he had managed to communicate his findings more effectively and avoid antagonising the medical establishment, even given the opposition from entrenched viewpoints.

[58][59][60] He also called upon Siebold to arrange a meeting of German obstetricians somewhere in Germany to provide a forum for discussions on puerperal fever, where he would stay "until all have been converted to his theory.

[62] It might have been third-stage syphilis, a then-common disease of obstetricians who examined thousands of women at gratis institutions, or it might have been emotional exhaustion from overwork and stress.

Many doctors, particularly in Germany, appeared quite willing to experiment with the practical hand washing measures that he proposed—although virtually everyone rejected his basic and ground-breaking innovation: that the disease had only one cause, lack of cleanliness.

[68] Gustav Adolf Michaelis, a professor at a maternity institution in Kiel, replied positively to Semmelweis' suggestions, but eventually committed suicide, feeling responsible for the death of his own cousin, whom he had examined after she gave birth.