History of Bay Area Rapid Transit

The final passenger run occurred on April 20, 1958 and the entire system was soon dismantled in favor of automobiles and buses and the explosive growth of highway construction.

Proposals for the modern rapid transit system now in service began in 1946 by Bay Area business leaders concerned with increased post-war migration and growing congestion in the region.

An Army-Navy task force concluded that an additional trans-bay crossing would soon be needed and recommended a tunnel; however, actual planning for a rapid transit system did not begin until the 1950s.

[4] The commission's 1957 final report concluded the most cost-effective solution for the Bay Area's traffic woes would be to form a transit district charged with the construction and operation of a high-speed rapid rail system linking the cities and suburbs.

In 1959 a bill was passed in the state legislature that provided for the entire cost of construction of the tube to be paid for with surplus toll revenues from the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge.

On the San Francisco side, the system would branch to the south along the Peninsula to Palo Alto, to the southwest along Mission Street to Balboa Park, to Daly City in the west using the existing Twin Peaks Tunnel, and a new Geary Subway leading to the Golden Gate Bridge connecting San Francisco to Novato in the northwest.

To keep the lightweight cars stable while exposed to high wind conditions on superelevated curves, the joint venture of Parsons Brinckerhoff-Tudor-Bechtel, general engineering consultants to the District, recommended a broad gauge.

The consultants report in 1964 recommended a gauge of 5 ft 6 in (1,676 mm), unusual in the United States, which they said would improve stability and comfort without an exponential increase in construction costs.

The enormous tasks to be undertaken were daunting, including the Transbay Tube, the two-level Market Street subway in San Francisco, the complex underground Oakland Wye junction, the Berkeley Hills Tunnel, more than a dozen underground stations in Berkeley, Oakland and San Francisco, along with new maintenance facilities throughout the system.

For the initial system, these included: the Sacramento Northern Railway right-of-way in Concord, Contra Costa Center and Walnut Creek; State Route 24 and Interstate 980 from the Berkeley Hills Tunnel to Oakland; Western Pacific Railroad from Fruitvale to Niles Canyon; Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway and Key System right-of-ways between Richmond and Berkeley (which also became the Ohlone Greenway and Richmond Greenway); and the San Francisco and San Mateo Electric Railway[7] and original Southern Pacific Ocean View Branch[17] right-of-ways to Daly City.

[33] Legislative analyst A. Alan Post opened an investigation immediately,[33][34] and brought in electrical engineering Professor Bill Wattenburg of the University of California, Berkeley as a consultant.

[35] An ATC failure caused the train to run off the end of the elevated track and crash to the ground, injuring four people on board,[36] and drawing national and international attention.

"[37] At the same time, management deemed that the ATC "could not now be trusted to detect one train stalled on the tracks in the path of another going at full speed," so automatic controls were dropped.

With some Bay Area freeways damaged or destroyed, BART trains, within five hours of the earthquake, were again running; full service resumed at 5 am the next day.

[49] Even with service interruptions following aftershocks for inspection of tracks, over- and under-crossings, and tunnels, BART continued to run on a 24-hour timetable until December 3 of that year.

The launch point was the Daly City Tailtrack project, which extended the tracks further south of the existing terminus in San Francisco and was completed in the 1980s.

Fueled by the reality that the extension was not paying for itself, the acrimony between BART and SamTrans over changes and reductions in bus and train service reached a high.

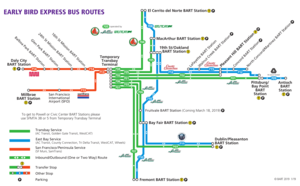

[67] (Long-term plans involve running short trains to a coupling point at Bay Fair to increase system-wide capacity while still providing a one-seat ride.)

The Coliseum–Oakland International Airport line, as it came to be known, utilizes automated guideway transit (AGT) technology: cable-drawn cars that operate in discrete cable loops on guided rubber tires.

This allowed BART to roll out service at 60% the cost of traditional buildout[citation needed] with the option to regauge and electrify the route at a later date.

In 2017, citing lack of interest in the project from BART, the Livermore City Council proposed a newly established local entity to undertake planning and construction of the extension,[72] which was also recommended by the California State Assembly Transportation Committee.

[76] In 2000, Santa Clara County voters approved a 30-year-long half cent sales tax increase to fund a BART extension to San Jose.

Despite the robustness of the system following the 1989 Loma Prieta quake, a 2010 study showed that BART overhead structures could collapse in a major earthquake,[81] which has a significant probability of occurring within three decades.

[82] Seismic retrofits were necessary to address these deficiencies, although one in particular, the penetration of the Hayward Fault Zone by the Berkeley Hills Tunnel, will be left for correction after a large earthquake.

An earthquake early warning system called ShakeAlert, sponsored by the United States Geological Survey, was instituted in 2012 with the help of UC Berkeley seismologists who linked BART to 200 stations of the California Integrated Seismic Network.

Oakland civil rights attorney John Burris filed a US$25 million wrongful death claim against the district on behalf of Grant's daughter and girlfriend.

[114] Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, ridership plummeted by 90% prompting reduced service hours,[115] cut short turns on the Antioch Line,[116] and longer train lengths to accommodate social distancing.

[117] Federal financial aid was provided to maintain service levels, with BART being particularly affected by loss of ridership due to its relatively high farebox recovery.

[citation needed] In its 2001 negotiations, the BART unions fought for, and won, a 24 percent wage increase over four years with continuing benefits for employees and retirees.

[147] On July 10, 1995, BART began limited direct service between Concord and Bay Fair as traffic mitigation during reconstruction of the I-680/SR 24 interchange in Walnut Creek.