History of the Ming dynasty

[3] Although private maritime trade and official tribute missions from China took place in previous dynasties, the size of the tributary fleet under the Muslim eunuch admiral Zheng He in the 15th century surpassed all others in grandeur.

Alongside institutionalized ethnic discrimination against the Han people that stirred resentment and rebellion, other explanations for the Yuan's demise included overtaxing areas hard-hit by crop failure, inflation, and massive flooding of the Yellow River as a result of the abandonment of irrigation projects.

[36] Modern scholars still debate on whether or not the Ming dynasty really had sovereignty over Tibet at all, as some believe it was a relationship of loose suzerainty which was largely cut off when the Jiajing Emperor (r. 1521–1567) persecuted Buddhism in favor of Daoism at court.

[52] The Wanli Emperor (r. 1572–1620) made attempts to reestablish Sino-Tibetan relations in the wake of a Mongol-Tibetan alliance initiated in 1578, the latter of which affected the foreign policy of the subsequent Manchu Qing dynasty (1644–1912) of China in their support for the Dalai Lama of the Yellow Hat sect.

[36][59][60][61][62] By the late 16th century, the Mongols proved to be successful armed protectors of the Yellow Hat Dalai Lama after their increasing presence in the Amdo region, culminating in Güshi Khan's (1582–1655) conquest of Tibet in 1642.

[36][63][64][65] In the first half of the Ming era, scholar-officials would rarely mention the contribution of merchants in society while writing their local gazetteer;[67] officials were certainly capable of funding their own public works projects, a symbol of their virtuous political leadership.

[68] However, by the second half of the Ming era it became common for officials to solicit money from merchants in order to fund their various projects, such as building bridges or establishing new schools of Confucian learning for the betterment of the gentry.

Writings of family instructions for lineage groups in the late Ming period display the fact that one no longer inherited his position in the categorization of the four occupations (in descending order): gentry, farmers, artisans, and merchants.

[75] The shipwrecked Korean Ch'oe Pu (1454–1504) remarked in 1488 how the locals along the eastern coasts of China did not know the exact distances between certain places, which was virtually exclusive knowledge of the Ministry of War and courier agents.

Qiu Jun (1420–1495), a scholar-official from Hainan, argued that the state should only mitigate market affairs during times of pending crisis and that merchants were the best gauge in determining the strength of a nation's riches in resources.

[81] The governments of the Hongwu and Zhengtong (r. 1435–1449) emperors attempted to cut the flow of silver into the economy in favor of paper currency,[81][82] yet mining the precious metal simply became a lucrative illegal pursuit practiced by many.

[82] The failure of these stern regulations against silver mining prompted ministers such as the censor Liu Hua (jinshi graduate in 1430) to support the baojia system of communal self-defense units to patrol areas and arrest 'mining bandits' (kuangzei).

[84] The historian Tanaka Masatoshi regarded "Deng's uprising as the first peasant rebellion that resisted the class relationship of rent rather than the depredations of officials, and therefore as the first genuinely class-based 'peasant warfare' in Chinese history.

[20] The value of standard copper coinage dropped significantly as well due to counterfeit minting; by the 16th century, new maritime trade contacts with Europe provided massive amounts of imported silver, which increasingly became the common medium of exchange.

"[103] Yet the Great Wall was not meant to be a purely defensive fortification; its towers functioned rather as a series of lit beacons and signalling stations to allow rapid warning to friendly units of advancing enemy troops.

A massive drought in August 1457 forced over five hundred Mongol families living on the steppe to seek refuge in Ming territories, entering through the Piantou Pass of northwestern Shanxi.

[119] In July 1461, after Mongols had staged raids in June into Ming territory along the northern tracts of the Yellow River, the Minister of War Ma Ang (1399–1476) and General Sun Tang (died 1471) were appointed to lead a force of 15,000 troops to bolster the defenses of Shaanxi.

[122] On the previous day, the emperor issued an edict telling his nobles and generals to be loyal to the throne; this was in effect a veiled threat to Cao Qin, after the latter had his associate in the Jinyiwei beaten to death to cover up crimes of illegal foreign transactions.

[103] Instead of mounting a counterattack, Ming authorities chose to shut down coastal facilities and starve the pirates out; all foreign trade was to be conducted by the state under the guise of formal tribute missions.

[139] The History of Ming, compiled during the early Qing dynasty, describes how the Hongwu Emperor met with an alleged merchant of Fu lin (拂菻; i.e. the Byzantine Empire) named "Nieh-ku-lun" (捏古倫).

[152] The Portuguese friar Gaspar da Cruz (c. 1520 – 5 February 1570) traveled to Guangzhou in 1556 and wrote the first book on China and the Ming dynasty that was published in Europe (fifteen days after his death); it included information on its geography, provinces, royalty, official class, bureaucracy, shipping, architecture, farming, craftsmanship, merchant affairs, clothing, religious and social customs, music and instruments, writing, education, and justice.

This included sweet potatoes, maize, and peanuts, foods that could be cultivated in lands where traditional Chinese staple crops—wheat, millet, and rice—couldn't grow, hence facilitating a rise in the population of China.

They bring domestic buffaloes; geese that resemble swans; horses, some mules and asses; even caged birds, some of which talk, while others sing, and they make them play innumerable tricks...pepper and other spices.

[168][169] Annoyed by all of this, the Wanli Emperor began neglecting his duties, remaining absent from court audiences to discuss politics, lost interest in studying the Confucian Classics, refused to read petitions and other state papers, and stopped filling the recurrent vacancies of vital upper level administrative posts.

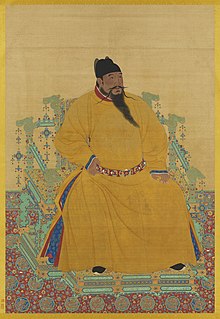

[94] Whether or not these restrictions were carried out with absolute success in his reign, eunuchs in the Yongle era and after managed huge imperial workshops, commanded armies, and participated in matters of appointment and promotion of officials.

[170][171][172] Complaints about eunuchs abusing their powers of taxation, as well as tales of sexual predations and occult practices, surface in popular culture works such as Zhang Yingyu's "The Book of Swindles" (ca.

[177] In this early half of the 17th century, famines became common in northern China because of unusual dry and cold weather that shortened the growing season; these were effects of a larger ecological event now known as the Little Ice Age.

[192] The agreement soon broke down when a local magistrate had thirty-six of his fellow rebels executed; Li's troops retaliated by killing the officials and continued to lead a rebellion based in Rongyang, central Henan province by 1635.

[194] On 26 May 1644, Beijing fell to a rebel army led by Li Zicheng; during the turmoil, Chongzhen, the last Ming emperor, accompanied only by a eunuch servant, hanged himself on a tree in the imperial garden right outside the Forbidden City.

[196] After being forced out of Xi'an by the Manchus, chased along the Han River to Wuchang, and finally along the northern border of Jiangxi province, Li Zicheng died there in the summer of 1645, thus ending the Shun dynasty.