History of vegetarianism

[22] According to the Vinaya Pitaka, the first schism happened when the Buddha was still alive: a group of monks led by Devadatta left the community because they wanted stricter rules, including an unconditional ban on meat eating.

[22] The Mahaparinibbana Sutta, which narrates the end of the Buddha's life, states that he died after eating sukara-maddava, a term translated by some as pork, by others as mushrooms (or an unknown vegetable).

He promulgated detailed laws aimed at the protection of many species, abolished animal sacrifice at his court, and admonished the population to avoid all kinds of unnecessary killing and injury.

The early history of Indian dietary practices, especially during the Vedic period, was shaped by the concept of the Guṇa – a central term in Hindu philosophy that refers to qualities or attributes.

[32] Philosopher Michael Allen Fox asserts that "Hinduism has the most profound connection with a vegetarian way of life and the strongest claim to fostering and supporting it.

[39] Many Vaishnava schools avoid vegetables such as onion, garlic, leek, radish, carrot, brinjal (eggplant), bottle gourd, mushrooms, red lentils, etc., as they are considered to have non-saatvik effects on the body.

[42] Eudoxus of Cnidus, a student of Archytas and Plato, writes that "Pythagoras was distinguished by such purity and so avoided killing and killers that he not only abstained from animal foods, but even kept his distance from cooks and hunters".

[49] Both Orphics and strict Pythagoreans also avoided eggs and shunned the ritual offerings of meat to the gods which were an essential part of traditional religious sacrifice.

In that utopian state of the world hunting, livestock breeding, and meat-eating, as well as agriculture were unknown and unnecessary, as the earth spontaneously produced in abundance all the food its inhabitants needed.

[64] Among the Manicheans, a major religious movement founded in the third century CE, there was an elite group called Electi (the chosen) who were Lacto-Vegetarians for ethical reasons and abided by a commandment which strictly banned killing.

This practice is not merely ascetic but reflects the belief in Chinese spirituality that animals possess immortal souls, and that a grain-based diet is the healthiest for humans.

While the percentage of people who are permanently vegetarian in China is similar to that in the modern English-speaking world, this proportion has remained relatively unchanged for a long time.

[74] In 675, the use of livestock and the consumption of some wild animals (horse, cattle, dogs, monkeys, birds) was banned in Japan by Emperor Tenmu, due to the influence of Buddhism.

The leaders of the early Christians in the apostolic era (James, Peter, and John) were concerned that eating food sacrificed to idols might result in ritual pollution.

[citation needed] The Apostle Paul emphatically rejected that view which resulted in division of an Early Church (Romans 14:2-21; compare 1 Corinthians 8:8-9, Colossians 2:20-22).

[89] William of Malmesbury writes that Bishop Wulfstan of Worcester (d. 1095) decided to adhere to a strict vegetarian diet simply because he found it difficult to resist the smell of roasted goose.

Medieval hermits, at least those portrayed in literature, may have been vegetarians for similar reasons, as suggested in a passage from Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur: 'Then departed Gawain and Ector as heavy (sad) as they might for their misadventure, and so rode till that they came to the rough mountain, and there they tied their horses and went on foot to the hermitage.

'[92] John Passmore claimed that there was no surviving textual evidence for ethically motivated vegetarianism in either ancient and medieval Catholicism or in the Eastern Churches.

[5][93] Many ancient intellectual dissidents, such as the Encratites, the Ebionites, and the Eustathians who followed the fourth century monk Eustathius of Antioch, considered abstention from meat-eating an essential part of their asceticism.

[94] Medieval Paulician Adoptionists, such as the Bogomils ("Friends of God") of the Thrace area in Bulgaria and the Christian dualist Cathars, also despised the consumption of meat.

[97] In the 17th century the paramount theorist of the meatless or Pythagorean diet was the English writer Thomas Tryon (1634–1703), who published the vegetarian text The Way to Health, Long Life and Happiness in 1683.

By the end of the 18th century in England the claim that animals were made only for man's use (anthropocentrism) was still being advanced, but no longer carried general assent.

Though the meat industry was growing substantially, many working class Britons had mostly vegetarian diets out of necessity rather than out of the desire to improve their health and morals.

[145] Dr. John Harvey Kellogg (of corn flakes fame), a Seventh-Day Adventist, promoted vegetarianism at his Battle Creek Sanitarium as part of his theory of "biologic living".

Inspired by Jean-Jacques Rousseau's treatise Emile: or, On Education, Struve promoted vegetarianism as part of his broader vision for social reform.

[149] In the late 19th century, numerous vegetarian associations were founded in Germany, with the Order of the Golden Age gaining particular prominence beyond the food reform movement.

[citation needed] Historian Albert Wirz notes that the trend toward vegetarianism before World War I was partly a reaction to the social upheavals caused by industrialization and globalization.

[151] The modern vegetarian movement also saw the involvement of figures like Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche and her husband Bernhard Förster, who founded the utopian colony Nueva Germania in Paraguay in 1886.

[163] The study of Far-Eastern religious and philosophical concepts of nonviolence was also instrumental in the shaping of Albert Schweitzer's principle of "reverence for life", which is still today a common argument in discussions on ethical aspects of diet.

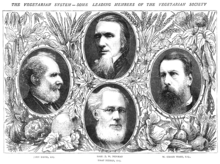

When the request was turned down, Donald Watson, secretary of the Leicester branch, set up a new quarterly newsletter in November 1944 called it The Vegan News.