Women's suffrage in the United States

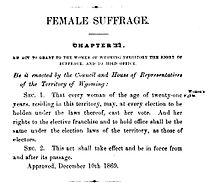

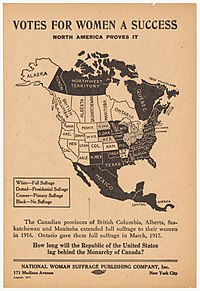

[3] The first state to grant women the right to vote had been Wyoming,[6] in 1869, followed by Utah[7] in 1870, Colorado in 1893, Idaho in 1896, Washington[8] in 1910, California[9] in 1911, Oregon[10] and Arizona[11] in 1912, Montana in 1914, North Dakota, New York,[12] and Rhode Island[13] in 1917, Louisiana,[14] Oklahoma,[15] and Michigan[16] in 1918.

When the Grimké sisters, who had been born into a slave-holding family in South Carolina, spoke against slavery throughout the northeast in the mid-1830s, the ministers of the Congregational Church, a major force in that region, published a statement condemning their actions.

"[40] Married women in many states could not legally sign contracts, which made it difficult for them to arrange for convention halls, printed materials, and other things needed by the suffrage movement.

[41] Restrictions like these were overcome in part by the passage of married women's property laws in several states, supported in some cases by wealthy fathers who did not want their daughters' inheritance to fall under the complete control of their husbands.

William Lloyd Garrison, the leader of the American Anti-Slavery Society, said "I doubt whether a more important movement has been launched touching the destiny of the race, than this in regard to the equality of the sexes".

[46] A convention of the Liberty Party in Rochester, New York in May 1848 approved a resolution calling for "universal suffrage in its broadest sense, including women as well as men.

"[47] Gerrit Smith, its candidate for president, delivered a speech shortly afterwards at the National Liberty Convention in Buffalo, New York, that elaborated on his party's call for women's suffrage.

When her husband, a well-known social reformer, learned that she intended to introduce this resolution, he refused to attend the convention and accused her of acting in a way that would turn the proceedings into a farce.

[62] Reports of this convention reached Britain, prompting Harriet Taylor, soon to be married to philosopher John Stuart Mill, to write an essay called "The Enfranchisement of Women," which was published in the Westminster Review.

[3] Their decades-long collaboration was pivotal for the suffrage movement and contributed significantly to the broader struggle for women's rights, which Stanton called "the greatest revolution the world has ever known or ever will know.

[82] Its 5000 members constituted a widespread network of women activists who gained experience that helped create a pool of talent for future forms of social activism, including suffrage.

In April 1867, Stone and her husband, Henry Blackwell, opened the AERA campaign in Kansas in support of referendums in that state that would enfranchise both African Americans and women.

Anthony and Stanton were harshly criticized by Stone and other AERA members for accepting help during the last days of the campaign from George Francis Train, a wealthy businessman who supported women's rights.

One wing, whose leading figure was Lucy Stone, was willing for black men to achieve suffrage first, if necessary, and wanted to maintain close ties with the Republican Party and the abolitionist movement.

Anthony and Stanton wrote a letter to the 1868 Democratic National Convention that criticized Republican sponsorship of the Fourteenth Amendment (which granted citizenship to black men but for the first time introduced the word "male" into the Constitution), saying, "While the dominant party has with one hand lifted up two million black men and crowned them with the honor and dignity of citizenship, with the other it has dethroned fifteen million white women – their own mothers and sisters, their own wives and daughters – and cast them under the heel of the lowest orders of manhood.

In some cases, actions like these preceded the New Departure strategy: in 1868 in Vineland, New Jersey, a center for radical spiritualists, nearly 200 women placed their ballots into a separate box and attempted to have them counted, but without success.

[133] Calling attention to the irony of being legally entitled to run for office while denied the right to vote, Elizabeth Cady Stanton declared herself a candidate for the U.S. Congress in 1866, the first woman to do so.

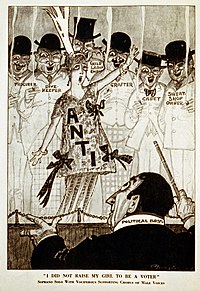

[187]The New York State Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (NYSAOWS) used grass roots mobilization techniques they had learned from watching the suffragists to defeat the 1915 referendum.

The threat of these reforms united planters, textile mill owners, railroad magnates, city machine bosses, and the liquor interest in a formidable combine against suffrage.

[232] This would, as Laura Clay stated in a debate with Kentucky Equal Rights Association president Madeline McDowell Breckinridge,[233] raise the spectre of Reconstruction Era interventions and bring increased federal scrutiny of elections in the South.

[235] In 1870, shortly after the formation of the AWSA, Lucy Stone launched an eight-page weekly newspaper called the Woman's Journal to advocate for women's rights, especially suffrage.

"[257] In the 1918 elections, despite the threat of Spanish flu, three additional states (Oklahoma, South Dakota, and Michigan) passed ballot initiatives to enfranchise women, and two incumbent senators (John W. Weeks of Massachusetts and Willard Saulsbury Jr. of Delaware) lost re-election campaigns due to their opposition to suffrage.

[259] Political leaders who became convinced of the inevitability of women's suffrage began to pressure local and national legislators to support it so that their respective party could claim credit for it in future elections.

Women played a major role on the home fronts and many countries recognized their sacrifices with the vote during or shortly after the war, including the U.S., Britain, Canada (except Quebec), Denmark, Austria, the Netherlands, Germany, Russia, Sweden; and Ireland introduced universal suffrage with independence.

Politicians responded to the newly enlarged electorate by emphasizing issues of special interest to women, especially prohibition, child health, public schools, and world peace.

[284][282] The Naturalization Act of 1790 granted any free white, who met character and residency policies, the right to become a citizen and the 14th Amendment extended citizenship to those born in the United States, including African-Americans.

[308] In 1921, the U.S. Supreme Court clarified that constitutional rights did not extend to residents in the two territories as they were defined in Puerto Rico by the Organic Act of 1900 and in the Virgin Islands by the Danish Colonial Law of 1906.

The paper concluded that women's voting appeared to be more risk-averse than men and favored candidates or policies that supported wealth transfer, social insurance, progressive taxation, and larger government.

[332] Many leaders of the National Woman's Party co-habitated with other women involved in feminist politics: Alma Lutz and Marguerite Smith, Jeanette Marks and Mary Wooley, and Mabel Vernon and Consuelo Reyes.

[334] There are also the significant same sex relationships of NAWSA first and second vice presidents Jane Addams and Sophonisba Breckenridge, respectively,[335] and the chronic close female friendships of Alice Paul.

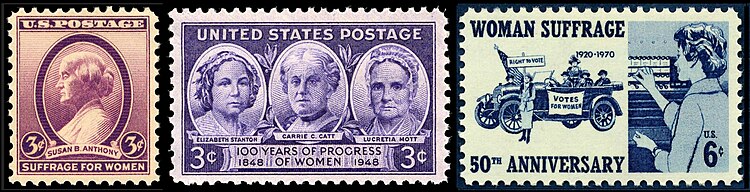

— Susan B Anthony , 1936 issue

— Elizabeth Stanton , Carrie C. Catt , Lucretia Mott , 1948 issue

— Women Suffrage , 1970 issue, celebrating the 50th anniversary of voting rights for women