Holodomor

While most scholars are in consensus that the main cause of the famine was largely man-made, it remains in dispute whether the Holodomor was intentional and whether it was directed at Ukrainians and whether it constitutes a genocide, the point of contention being the absence of attested documents explicitly ordering the starvation of any area in the Soviet Union.

[29] Holodomor is now an entry in the modern, two-volume dictionary of the Ukrainian language, published in 2004, described as "artificial hunger, organised on a vast scale by a criminal regime against a country's population.

By the beginning of February 1933, according to reports from local authorities and Ukrainian GPU (secret police), the most affected area was Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, which also suffered from epidemics of typhus and malaria.

Among contemporary historians it is debated whether the famine was an intended result of such policies,[48] whether the Holodomor was directed at Ukrainians, and whether it constitutes a genocide, the point of contention being the absence of attested documents explicitly ordering the starvation of any area in the Soviet Union.

[64] Leon Trotsky, however, opposed the policy of forced collectivisation under Stalin and would have favoured a voluntary, gradual approach towards collective farming[65][66] with greater tolerance for the rights of Soviet Ukrainians.

According to Natalya Naumenko, collectivization in the Soviet Union and lack of favored industries were primary contributors to famine mortality (52% of excess deaths), and some evidence shows there was discrimination against ethnic Ukrainians and Germans.

[6] The collectivization and high procurement quota explanation for the famine is somewhat called into question by the fact that the oblasts of Ukraine with the highest losses were Kyiv and Kharkiv, which produced far lower amounts of grain than other sections of the country.

[82] Mark Tauger criticized Natalya Naumenko's work as being based on: "major historical inaccuracies and falsehoods, omissions of essential evidence contained in her sources or easily available, and substantial misunderstandings of certain key topics".

[42] The collectivization and high procurement quota explanation for the famine is called into question by the fact that the oblasts of Ukraine with the highest losses were Kyiv and Kharkiv, which produced far lower amounts of grain than other sections of the country.

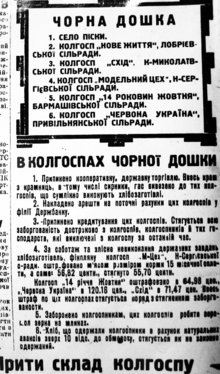

"[85] Several repressive policies were implemented in Ukraine immediately preceding, during, and proceeding the famine, including but not limited to cultural-religious persecution the Law of Spikelets, Blacklisting, the internal passport system, and harsh grain requisitions.

[102] Although nominally targeting collective farms failing to meet grain quotas and independent farmers with outstanding tax-in-kind, in practice the punishment was applied to all residents of affected villages and raions, including teachers, tradespeople, and children.

[6] In contrast, historian Stephen Kotkin argues that the sealing of the Ukrainian borders caused by the internal passport system was in order to prevent the spread of famine-related diseases.

According to Oleh Wolowyna, 390 "anti-Soviet, counter-revolutionary insurgent and chauvinist" groups were eliminated resulting in 37,797 arrests, that led to 719 executions, 8,003 people being sent to Gulag camps, and 2,728 being put into internal exile.

During Holodomor people brought family heritage - crosses, earrings, wedding rings to Torgsins and exchanged it for special stamps, for which they could obtain basic goods - mostly flour, cereals or sugar.

To justify this Kaganovich cited a letter allegedly written by a stanitsa ataman named Grigorii Omel'chenko advocating Cossack separatism and local reports of resistance to collectivization in association with this figure to substantiate this suspicion of the area.

[3] However Kaganocvich did not reveal in speeches throughout the region that many of those targeted by persecution in Poltavskaia had their family members and friends deported or shot including in years before the supposed Omel'chenko crisis even started.

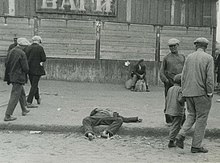

[4] Despite attempts by the Soviet authorities to hide the scale of the disaster, it became known abroad thanks to the publications of journalists Gareth Jones, Malcolm Muggeridge, Ewald Ammende and Rhea Clyman, and photographs made by engineer Alexander Wienerberger and others.

To support their denial of the famine, the Soviets hosted prominent Westerners such as George Bernard Shaw, French ex-prime minister Édouard Herriot, and others at Potemkin villages, who then made statements that they had not seen hunger.

[citation needed] In 1942, Stepan Sosnovy, an agronomist in Kharkiv, published a comprehensive statistical research on the number of Holodomor casualties, based on documents from Soviet archives.

[142] In the 1980s, dissident demographer and historian Alexander P. Babyonyshev (writing as Sergei Maksudov) estimated officially non-accounted child mortality in 1933 at 150,000,[143] leading to a calculation that the number of births for 1933 should be increased from 471,000 to 621,000 (down from 1,184,000 in 1927).

[citation needed] In the 2000s, there were debates among historians and in civil society about the number of deaths as Soviet files were released and tension built between Russia and the Ukrainian president Viktor Yushchenko.

Snyder also estimates that of the million people who died in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic from famine at the same time, approximately 200,000 were ethnic Ukrainians due to Ukrainian-inhabited regions being particularly hard hit in Russia.

The decision was criticized by David R. Marples, who claimed that states who recognize the Holodomor as a genocide are motivated by emotion, or on pressure by local and international groups rather than hard evidence.

[102]: 35 Stanislav Kulchytsky, who recognizes Holodomor as genocide, believes that historians should approach the study of the famine with realization that in the Soviet socialist construction "appearance belied reality", and that the real intentions of some ideas and policies would not be put on paper.

In the exchange, Conquest wrote that he is now of the opinion that the Holodomor was not purposefully inflicted by Stalin but "What I argue is that with resulting famine imminent, he could have prevented it, but put "Soviet interest" other than feeding the starving first – thus consciously abetting it".

Ukrainian historian Stanislav Kulchytsky stated the Soviet government ordered him to falsify his findings and depict the famine as an unavoidable natural disaster, to absolve the Communist Party and uphold the legacy of Stalin.

Honouring the seventieth anniversary of the Ukrainian tragedy, we also commemorate the memory of millions of Russians, Kazakhs and representatives of other nationalities who died of starvation in the Volga River region, Northern Caucasus, Kazakhstan and in other parts of the former Soviet Union, as a result of civil war and forced collectivisation, leaving deep scars in the consciousness of future generations.

In 2010, the Kyiv Court of Appeal ruled that the Holodomor was an act of genocide and held Joseph Stalin, Vyacheslav Molotov, Lazar Kaganovich, Stanislav Kosior, Pavel Postyshev, Mendel Khatayevich, Vlas Chubar and other Bolshevik leaders responsible.

[288] On 16 March 2006, the Senate of the Republic of Poland paid tribute to the victims of the Great Famine and declared it an act of genocide, expressing solidarity with the Ukrainian nation and its efforts to commemorate this crime.

The statement released by the White House Press Secretary reflects on the significance of this date, stating that "in the wake of this brutal and deliberate attempt to break the will of the people of Ukraine, Ukrainians showed great courage and resilience.