Holy Roman Empire

He argues that the Ottonian empire was hardly an archaic kingdom of primitive Germans, maintained by personal relationships only and driven by the desire of the magnates to plunder and divide the rewards among themselves but instead, notable for their abilities to amass sophisticated economic, administrative, educational and cultural resources that they used to serve their enormous war machine.

[48] In the late 5th and early 6th centuries, the Merovingians, under Clovis I and his successors, consolidated Frankish tribes and extended hegemony over others to gain control of northern Gaul and the middle Rhine river valley region.

[55][56] Although antagonism about the expense of Byzantine domination had long persisted within Italy, a political rupture was set in motion in earnest in 726 by the iconoclasm of Emperor Leo III the Isaurian, in what Pope Gregory II saw as the latest in a series of imperial heresies.

As the Latin Church only regarded a male Roman emperor as the head of Christendom, Pope Leo III sought a new candidate for the dignity, excluding consultation with the patriarch of Constantinople.

[84] Otto III's (and his mentor Pope Sylvester's) diplomatic activities coincided with and facilitated the Christianization and the spread of Latin culture in different parts of Europe.

[101][102] This was an attempt to abolish private feuds, between the many dukes and other people, and to tie the emperor's subordinates to a legal system of jurisdiction and public prosecution of criminal acts – a predecessor of the modern concept of rule of law.

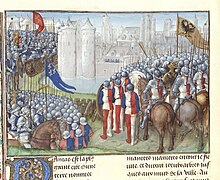

[clarification needed] Pope Innocent III, who feared the threat posed by a union of the empire and Sicily, was now supported by Frederick II, who marched to Germany and defeated Otto.

[107] In the Kingdom of Sicily and much of Italy, Frederick built upon the work of his Norman predecessors and forged an early absolutist state bound together by an efficient secular bureaucracy.

These provisions not withstanding, royal power in Germany remained strong under Frederick and by the 1240s the crown was still rich in fiscal resources, land holdings, retinues, and all other rights, revenues, and jurisdictions.

[108] The Mainz Landfriede or Constitutio Pacis, decreed at the Imperial Diet of 1235, became one of the basic laws of the empire and provided that the princes should share the burden of local government in Germany.

During the 13th century, a general structural change in how land was administered prepared the shift of political power toward the rising bourgeoisie at the expense of the aristocratic feudalism that would characterize the Late Middle Ages.

[115] Thomas Brady Jr. opines that Charles IV's intention was to end contested royal elections (from the Luxembourghs' perspective, they also had the advantage that the King of Bohemia had a permanent and preeminent status as one of the Electors himself).

According to Brady Jr. though, under all the glitter, one problem arose: the government showed an inability to deal with the German immigrant waves into Bohemia, thus leading to religious tensions and persecutions.

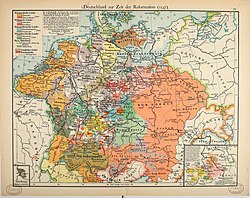

[154][155] The development of the printing industry together with the emergence of the postal system (the first modern one in the world),[156] initiated by Maximilian himself with contribution from Frederick III and Charles the Bold, led to a revolution in communication and allowed ideas to spread.

Pearson that this distinctively European phenomenon happened because in the Italian and Hanseatic cities which lacked resources and were "small in size and population", the rulers (whose social status was not much higher than the merchants) had to pay attention to trade.

From Maximilian's time, as the "terminuses of the first transcontinental post lines" began to shift from Innsbruck to Venice and from Brussels to Antwerp, in these cities, the communication system and the news market started to converge.

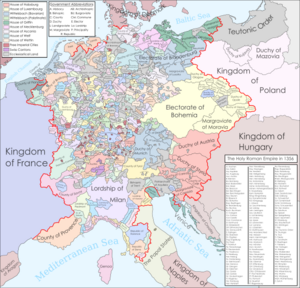

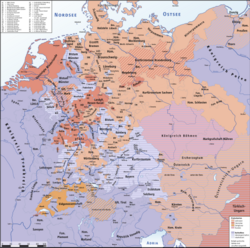

The empire then became divided along religious lines, with the north, the east, and many of the major cities – Strasbourg, Frankfurt, and Nuremberg – becoming Protestant while the southern and western regions largely remained Catholic.

From the High Middle Ages onwards, the Holy Roman Empire was marked by an uneasy coexistence with the princes of the local territories who were struggling to take power away from it.

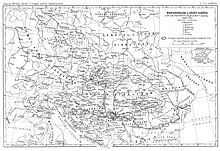

In 1356, Emperor Charles IV issued the Golden Bull, which limited the electors to seven: the King of Bohemia, the Count Palatine of the Rhine, the Duke of Saxony, the Margrave of Brandenburg, and the archbishops of Cologne, Mainz, and Trier.

Kings and emperors toured between the numerous Kaiserpfalzes (Imperial palaces), usually resided for several weeks or months and furnished local legal matters, law and administration.

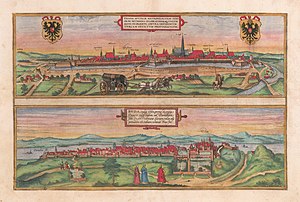

Most rulers maintained one or a number of favourites Imperial palace sites, where they would advance development and spent most of their time: Charlemagne (Aachen from 794), Otto I (Magdeburg, from 955),[219] Frederick II (Palermo 1220–1254), Wittelsbacher (Munich 1328–1347 and 1744–1745), Habsburger (Prague 1355–1437 and 1576–1611; and Vienna 1438–1576, 1611–1740 and 1745–1806).

[226][227] The Imperial Diet (Reichstag) resided variously in Paderborn, Bad Lippspringe, Ingelheim am Rhein, Diedenhofen (now Thionville), Aachen, Worms, Forchheim, Trebur, Fritzlar, Ravenna, Quedlinburg, Dortmund, Verona, Minden, Mainz, Frankfurt am Main, Merseburg, Goslar, Würzburg, Bamberg, Schwäbisch Hall, Augsburg, Nuremberg, Quierzy-sur-Oise, Speyer, Gelnhausen, Erfurt, Eger (now Cheb), Esslingen, Lindau, Freiburg, Cologne, Konstanz and Trier before it was moved permanently to Regensburg.

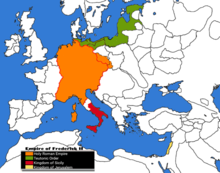

Henry VI, inheriting both German aspirations for imperial sovereignty and the Norman Sicilian kings' dream of hegemony in the Mediterranean, had ambitious design for a world empire.

[239][240] In its earlier days, the Empire provided the principal medium for Christianity to infiltrate the pagans' realms in the North and the East (Scandinavians, Magyars, Slavic people etc.).

[241] By the Reform era, the Empire, in its nature, was defensive and not aggressive, desiring of both internal peace and security against invading forces, a fact that even warlike princes such as Maximilian I appreciated.

The successful expansion (with the notable role of marriage policy) under Maximilian bolstered his position in the Empire, and also created more pressure for an imperial reform, so that they could get more resources and coordinated help from the German territories to defend their realms and counter hostile powers such as France.

[252] In the reigns of his grandsons, Croatia and the remaining rump of the Hungarian kingdom chose Ferdinand as their ruler after he managed to rescue Silesia and Bohemia from Hungary's fate against the Ottoman.

Simms notes that their choice was a contractual one, tying Ferdinand's rulership in these kingdoms and territories to his election as King of the Romans and his ability to defend Central Europe.

"Instead, they developed their own institutions to manage what was, effectively, a parallel dynastic-territorial empire and which gave them an overwhelming superiority of resources, in turn allowing them to retain an almost unbroken grip on the imperial title over the next three centuries.

This changed once Hungary passed to the Habsburgs on Louis' death in battle in 1526 and the main objective of imperial taxation across the next 90 years was to subsidize the cost of defending the Hungarian frontier against the Ottomans.