Landscape painting

For a coherent depiction of a whole landscape, some rough system of perspective, or scaling for distance, is needed, and this seems from literary evidence to have first been developed in Ancient Greece in the Hellenistic period, although no large-scale examples survive.

Both the Roman and Chinese traditions typically show grand panoramas of imaginary landscapes, generally backed with a range of spectacular mountains – in China often with waterfalls and in Rome often including sea, lakes or rivers.

These were frequently used, as in the example illustrated, to bridge the gap between a foreground scene with figures and a distant panoramic vista, a persistent problem for landscape artists.

In the West this was history painting, but in East Asia it was the imaginary landscape, where famous practitioners were, at least in theory, amateur literati, including several emperors of both China and Japan.

[12] During the 14th century Giotto di Bondone and his followers began to acknowledge nature in their work, increasingly introducing elements of the landscape as the background setting for the action of the figures in their paintings.

[13] Early in the 15th century, landscape painting was established as a genre in Europe, as a setting for human activity, often expressed in a religious subject, such as the themes of the Rest on the Flight into Egypt, the Journey of the Magi, or Saint Jerome in the Desert.

A particular advance is shown in the less well-known Turin-Milan Hours, now largely destroyed by fire, whose developments were reflected in Early Netherlandish painting for the rest of the century.

Other painters who never crossed the Alps could make money selling Rhineland landscapes, and still others for constructing fantasy scenes for a particular commission such as Cornelis de Man's view of Smeerenburg in 1639.

Unlike their Dutch contemporaries, Italian and French landscape artists still most often wanted to keep their classification within the hierarchy of genres as history painting by including small figures to represent a scene from classical mythology or the Bible.

In England, landscapes had initially been mostly backgrounds to portraits, typically suggesting the parks or estates of a landowner, though mostly painted in London by an artist who had never visited his sitter's rolling acres.

In the 18th century, watercolour painting, mostly of landscapes, became an English specialty, with both a buoyant market for professional works, and a large number of amateur painters, many following the popular systems found in the books of Alexander Cozens and others.

[29] In Europe, as John Ruskin said,[30] and Sir Kenneth Clark confirmed, landscape painting was the "chief artistic creation of the nineteenth century", and "the dominant art", with the result that in the following period people were "apt to assume that the appreciation of natural beauty and the painting of landscape is a normal and enduring part of our spiritual activity"[31] In Clark's analysis, underlying European ways to convert the complexity of landscape to an idea were four fundamental approaches: the acceptance of descriptive symbols, a curiosity about the facts of nature, the creation of fantasy to allay deep-rooted fears of nature, and the belief in a Golden Age of harmony and order, which might be retrieved.

The topographical print, often intended to be framed and hung on a wall, remained a very popular medium into the 20th century, but was often classed as a lower form of art than an imagined landscape.

[37] Back in Spain, Haes took his students with him to paint in the countryside; under his teaching the "painters proliferated and took advantage of the new railway system to explore the furthest corners of the nation's topography.

The work of Thomas Cole, the school's generally acknowledged founder, has much in common with the philosophical ideals of European landscape paintings – a kind of secular faith in the spiritual benefits to be gained from the contemplation of natural beauty.

Some of the later Hudson River School artists, such as Albert Bierstadt, created less comforting works that placed a greater emphasis (with a great deal of Romantic exaggeration) on the raw, even terrifying power of nature.

Frederic Edwin Church, a student of Cole, synthesized the ideas of his contemporaries with those of European Old Masters and the writings of John Ruskin and Alexander von Humboldt to become the foremost American landscape painter of the century.

[41] Although certainly less dominant in the period after World War I, many significant artists still painted landscapes in the wide variety of styles exemplified by Edvard Munch, Georgia O'Keeffe, Charles E. Burchfield, Neil Welliver, Alex Katz, Milton Avery, Peter Doig, Andrew Wyeth, David Hockney and Sidney Nolan.

Landscape painting has been called "China's greatest contribution to the art of the world",[44] and owes its special character to the Taoist (Daoist) tradition in Chinese culture.

[45] William Watson notes that "It has been said that the role of landscape art in Chinese painting corresponds to that of the nude in the west, as a theme unvarying in itself, but made the vehicle of infinite nuances of vision and feeling".

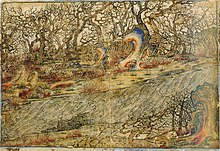

This shows the entourage riding through vertiginous mountains of the type typical of later paintings, but is in full colour "producing an overall pattern that is almost Persian", in what was evidently a popular and fashionable court style.

[48] The decisive shift to a monochrome landscape style, almost devoid of figures, is attributed to Wang Wei (699–759), also famous as a poet; mostly only copies of his works survive.

[49] From the 10th century onwards an increasing number of original paintings survive, and the best works of the Song dynasty (960–1279) Southern School remain among the most highly regarded in what has been an uninterrupted tradition to the present day.

There is a long tradition of the appreciation of "viewing stones" – naturally formed boulders, typically limestone from the banks of mountain rivers that has been eroded into fantastic shapes, were transported to the courtyards and gardens of the literati.

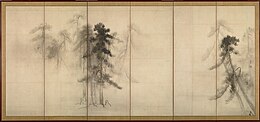

[57] Many more pure landscape subjects survive from the 15th century onwards; several key artists are Zen Buddhist clergy, and worked in a monochrome style with greater emphasis on brush strokes in the Chinese manner.

This combines one or more large birds, animals or trees in the foreground, typically to one side in a horizontal composition, with a wider landscape beyond, often only covering portions of the background.

The ukiyo-e style that developed from the 16th century onwards, first in painting and then in coloured woodblock prints that were cheap and widely available, initially concentrated on the human figure, individually and in groups.

[62] The distinctive background view across Lake Geneva to the Le Môle peak in The Miraculous Draught of Fishes by Konrad Witz (1444) is often cited as the first Western rural landscape to show a specific scene.

In woodcuts a large blank space can cause the paper to sag during printing, so Dürer and other artists often include clouds or squiggles representing birds to avoid this.

The monochrome Chinese tradition has used ink on silk or paper since its inception, with a great emphasis on the individual brushstroke to define the ts'un or "wrinkles" in mountain-sides, and the other features of the landscape.