Hugo Chávez

Hugo Rafael Chávez Frías[b] (/ˈtʃɑːvɛz/; Spanish: [ˈuɣo rafaˈel ˈtʃaβes ˈfɾi.as] ⓘ; 28 July 1954 – 5 March 2013) was a Venezuelan politician and military officer who served as the 52nd president of Venezuela from 1999 until his death in 2013, except for a brief period of forty-seven hours in 2002.

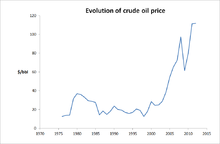

Using record-high oil revenues of the 2000s, his government nationalized key industries, created participatory democratic Communal Councils and implemented social programs known as the Bolivarian missions to expand access to food, housing, healthcare and education.

[12][13] The high oil profits coinciding with the start of Chavez's presidency[14] resulted in temporary improvements in areas such as poverty, literacy, income equality and quality of life between primarily 2003 and 2007,[15][14][16] though extensive changes in structural inequalities did not occur.

[18] By the end of Chávez's presidency in the early 2010s, economic actions performed by his government during the preceding decade, such as deficit spending[19][20][21] and price controls,[22][23] proved to be unsustainable, with Venezuela's economy faltering.

[51] In 1974, he was selected to be a representative in the commemorations for the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Ayacucho in Peru, the conflict in which Simon Bolívar's lieutenant, Antonio José de Sucre, defeated royalist forces during the Peruvian War of Independence.

[58] Nevertheless, hoping to gain an alliance with civilian leftist groups in Venezuela, Chávez set up clandestine meetings with various prominent Marxists, including Alfredo Maneiro (the founder of the Radical Cause) and Douglas Bravo.

After numerous betrayals, defections, errors, and other unforeseen circumstances, Chávez and a small group of rebels found themselves hiding in the Military Museum, unable to communicate with other members of their team.

[88] According to journalist Patricia Poleo, during his stay in Colombia, he spent six months receiving guerrilla training and establishing contacts with the FARC and ELN terrorist groups, and even adopted a nom de guerre Comandante Centeno.

Chávez's revolutionary rhetoric gained him support from Patria Para Todos (Homeland for All), the Partido Comunista Venezolano (Venezeuelan Communist Party) and the Movimiento al Socialismo (Movement for Socialism).

He deviated from the usual words of the presidential oath when he took it, proclaiming: "I swear before God and my people that upon this moribund constitution I will drive forth the necessary democratic transformations so that the new republic will have a Magna Carta befitting these new times".

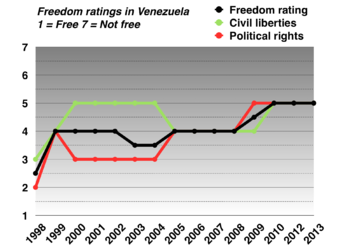

[97] Freedom in Venezuela suffered following "the decision of President Hugo Chávez, ratified in a national referendum, to abolish congress and the judiciary, and by his creation of a parallel government of military cronies".

[104] Low oil prices made Chavez's government reliant on international free markets during his first months in office, when he showed pragmatism and political moderation, and continued to encourage foreign investment in Venezuela.

[109] Chávez called a public referendum, which he hoped would support his plans to form a constituent assembly of representatives from across Venezuela and from indigenous tribal groups to rewrite the Venezuelan constitution.

[115] Chávez, following Castro's example, consolidated the country's bicameral legislature into a single National Assembly that gave him more power[111] and created community groups of loyal supporters allegedly trained as paramilitaries.

[citation needed] Chávez agreed to be detained and was transferred by army escort to La Orchila; business leader Pedro Carmona declared himself president of an interim government.

[140] Chávez's response was to moderate his approach,[disputed – discuss] implementing a new economic team that appeared to be more centrist and reinstated the old board of directors and managers of the state oil company Petróleos de Venezuela S.A. (PDVSA), whose replacement had been one of the reasons for the coup.

[141] At the same time, the Bolivarian government began to increase the country's military capacity, purchasing 100,000 AK-47 assault rifles and several helicopters from Russia, as well as a number of Super Tucano light attack and training planes from Brazil.

[citation needed] In May 2006, Chávez visited Europe in a private capacity, where he announced plans to supply cheap Venezuelan oil to poor working class communities in the continent.

"[187] He reiterated this position on 28 September 2001, when Chavez spoke negatively of neoliberal capitalism and the economic measures of the Carlos Andrés Pérez, El Gran Viraje [es], one of the causes of the Caracazo riots.

[201][non-primary source needed] Chávez's early heroes were nationalist military dictators that included former Peruvian president Juan Velasco Alvarado and former Panamanian "Maximum Leader" Omar Torrijos.

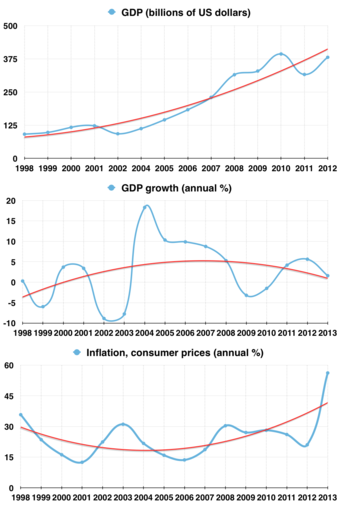

[213] The red line represents trends of annual rates given throughout the period shownFrom his election in 1998 until his death in March 2013, Chávez's administration proposed and enacted populist economic policies.

[214] Due to increasing oil prices in the early 2000s which raised funds not seen in Venezuela since the 1980s, Chávez created the Bolivarian Missions, aimed at providing public services to improve economic, cultural, and social conditions,[215][216][217][218] using these populist policies to maintain political power.

[221] The Missions, which were directly overseen by Chávez and often linked to his political campaigns,[214] entailed the construction of thousands of free medical clinics for the poor[215] and the enactment of food[217] and housing subsidies.

[20][218] Economists say that the Venezuelan government's overspending on social programs and strict business policies caused to imbalances in the country's economy, contributing to rising inflation, poverty, low healthcare spending and shortages in Venezuela going into the final years of his presidency.

[250] The red line represents what the Venezuelan government officially rates the hard bolívarSources: Banco Central de Venezuela, Dolar Paralelo, Federal Reserve Bank, International Monetary FundIn the first few years of Chavez's office, his newly created social programs required large payments to make the desired changes.

[269][270] He further explained that common criminals felt that the Venezuelan government did not care for the problems of the higher and middle classes, which in turn gave them a sense of impunity that created a large business of kidnapping-for-ransom.

[304] In 2004, Amnesty International criticized Chavez's administration of not handling the 2002 coup in a proper manner, saying that violent incidents "have not been investigated effectively and have gone unpunished" and that "impunity enjoyed by the perpetrators encourages further human rights violations in a particularly volatile political climate".

[305] Amnesty International also criticized the Venezuelan National Guard and the Direccion de Inteligencia Seguridad y Prevención (DISIP) stating that they "allegedly used excessive force to control the situation on a number of occasions" during protests involving the 2004 Venezuela recall.

[308] Subsequently, over a hundred Latin American scholars signed a joint letter with the Council on Hemispheric Affairs, a leftist NGO[309] that would defend Chávez and his movement, with the individuals criticizing the Human Rights Watch report for its alleged factual inaccuracy, exaggeration, lack of context, illogical arguments, and heavy reliance on opposition newspapers as sources, among other things.

[380][381] Chávez gave a public appearance on 28 July 2011, his 57th birthday, in which he stated that his health troubles had led him to radically reorient his life towards a "more diverse, more reflective and multi-faceted" outlook, and he went on to call on the middle classes and the private sector to get more involved in his Bolivarian Revolution, something he saw as "vital" to its success.

The red line represents trends of annual rates given throughout the period shown

GDP is in billions of Local Currency Unit that has been adjusted for inflationSources : International Monetary Fund , World Bank

The red line represents what the Venezuelan government officially rates the hard bolívar

Sources

: Banco Central de Venezuela, Dolar Paralelo, Federal Reserve Bank, International Monetary Fund

* UN line between 2007 and 2012 is simulated missing data

Source : CICPC [ 263 ] [ 264 ] [ 265 ]

* Express kidnappings may not be included in data

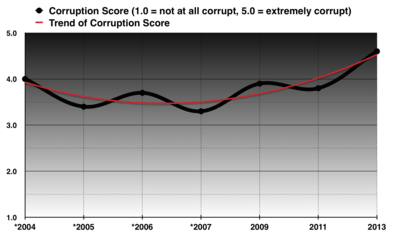

( * ) Score was averaged according to Transparency International's method.

Source : Transparency International

Source : Freedom House