Entomophagy in humans

[6] Human insect-eating is common to cultures in most parts of the world, including Central and South America, Africa, Asia, Australia, and New Zealand.

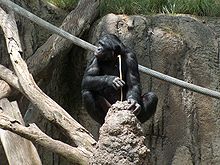

[21][22][23] The archaeological record, in the form of bone tools with wear marks, shows that early hominids such as Australopithecus robustus would gather termites for consumption.

[24] Lesnik also reviews multiple studies concluding that wear marks running along the length of the bone are indicative of tools used for digging up termite mounds.

[26] The remains of KNM-ER 1808, a specimen of Homo erectus dated to around 1.8 million years ago, has often been used as evidence for the hunter model due to its abnormal bone growths pointing to hypervitaminosis A from consuming excess animal liver.

Coprolites in caves in the Ozark Mountains were found to contain insects (ants, beetle larvae, lice), as well as arachnids (ticks, mites).

[29] Cave paintings in Altamira, north Spain, which have been dated from about 30,000 to 9,000 BC, depict the collection of edible insects and wild bee nests, suggesting a possibly entomophagous society.

Edible insects have long been used by ethnic groups in Asia,[30][31][32][33][34][35][36] Africa, Mexico and South America as cheap and sustainable sources of protein.

[8] The species include 235 butterflies and moths, 344 beetles, 313 ants, bees and wasps, 239 grasshoppers, crickets and cockroaches, 39 termites, and 20 dragonflies, as well as cicadas.

In southern Africa, the widespread moth Gonimbrasia belina's large caterpillar, the mopani or mopane worm, is a source of food protein.

[39] Traditionally several ethnic groups in Indonesia are known to consume insects—especially grasshoppers, crickets, termites, the larvae of the sago palm weevil, and bees.

In Java and Kalimantan, grasshoppers and crickets are usually lightly battered and deep fried in palm oil as a crispy kripik or rempeyek snack.

Traditional markets in Thailand often have stalls selling deep-fried grasshoppers, cricket (ching rit), bee larvae, silkworm (non mai), ant eggs (khai mot) and termites.

heros) is considered a strong candidate for identification of cossus by some authorities,[a] and while the stag beetle (Lucanus cervus) grub has also been considered a viable contender,[48] French entomologist Jean-Henri Fabre favored identification with the capricorn beetle's cousin[b] called ergat (Ergates faber), which he taste-tested himself, noting its almond-like flavor.

[57][58] It may be worth noting John the Baptist's "wild honey" is explained as tasting like manna, made into cakes, in the Gospel of the Ebionites.

Aspire Food Group was the first large-scale insect farming company in North America, using automated machinery in a 25,000-square-foot (2,300 m2) warehouse dedicated to raising organically grown house crickets for human consumption.

Western avoidance of entomophagy coexists with the consumption of other invertebrates such as molluscs and the insects' close arthropod relatives crustaceans, and is not associated with the taste or the perception food value.

[75] Public health nutritionist Alan Dangour has argued that large-scale entomophagy in Western culture faces "extremely large" barriers, which are "perhaps currently even likely to be insurmountable.

Examples can be found in Botswana, South Africa and Zimbabwe where strong cattle-raising traditions co-exist with entomophagy of insects like the mopane worm.

[88][89] While more attention is needed to fully assess the potential of edible insects, they provide a natural source of essential nutrients, offering an opportunity to bridge the gap in protein consumption between poor and wealthy nations and also to lighten the ecological footprint.

[90] Some argue that the combination of increasing land use pressure, climate change, and food grain shortages due to the use of maize as a biofuel feedstock will cause serious challenges for attempts to meet future protein demand.

Additionally, all insect species studied produced much lower amounts of ammonia than conventional livestock, though further research is needed to determine the long-term impact.

As the FAO states, animal livestock "emerges as one of the top two or three most significant contributors to the most serious environmental problems, at every scale from local to global.

Additionally, endothermic (warm-blooded) vertebrates need to use a significantly greater amount of energy just to stay warm, whereas ectothermic (cold-blooded) plants or insects do not.

[29] The intentional cultivation of insects and edible arthropods for human food is now emerging in animal husbandry as an ecologically sound concept.

Community cooperatives of cricket farmers have been established to disseminate information on technical farming, marketing and business issues, particularly in northeastern and northern Thailand.

"[79] Similarly, Julieta Ramos-Elorduy has stated that rural populations, who primarily "search, gather, fix, commercialize and store this important natural resource", do not exterminate the species which are valuable to their lives and livelihoods.

[83] Director of pediatric nutrition at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Frank Franklin has argued that since low calories and low protein are the main causes of death for approximately five million children annually, insect protein formulated into a ready-to-use therapeutic food similar to Nutriset's Plumpy'Nut could have potential as a relatively inexpensive solution to malnutrition.

[76] In 2009, Dr. Vercruysse from Ghent University in Belgium proposed that insect protein could be used to generate hydrolysates, exerting both ACE inhibitory and antioxidant activity, which might be incorporated as a multifunctional ingredient into functional foods.

[6] In 2012, Dr. Aaron T. Dossey announced that his company, All Things Bugs, had been named a Grand Challenges Explorations winner by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

The moths are very common and easy to catch by hand, and the low cyanogenic content makes Zygaena a minimally risky seasonal delicacy.