Echinococcosis

[1] When the liver is affected, the patient may experience abdominal pain, weight loss, along with yellow-toned skin discoloration from developed jaundice.

In 2020, an international effort of scientists, from 16 countries, led to a detailed consensus on terms to be used or rejected for the genetics, epidemiology, biology, immunology, and clinical aspects of echinococcosis.

In people who are infected with E. granulosus and therefore have cystic echinococcosis, the disease develops as a slow-growing mass in the body.

These slow-growing masses, often called cysts, are also found in people who are infected with alveolar and polycystic echinococcosis.

Humans function as accidental hosts, because they are usually a dead end for the parasitic infection cycle, unless eaten by dogs or wolves after death.

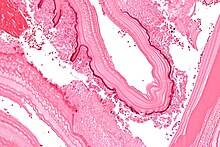

Once a cyst has reached a diameter of 1 cm, its wall differentiates into a thick outer, non-cellular membrane, which covers the thin germinal epithelium.

For instance, in E. multilocularis, the cysts have an ultra thin limiting membrane and the germinal epithelium may bud externally.

Humans are accidental intermediate hosts that become infected by handling soil, dirt, or animal hair that contains eggs.

[29] A formal diagnosis of any type of echinococcosis requires a combination of tools that involve imaging techniques, histopathology, or nucleic acid detection and serology.

The imaging technique of choice for cystic echinococcosis is ultrasonography, since it is not only able to visualize the cysts in the body's organs,[30] but it is also inexpensive, non-invasive and gives instant results.

[19] In addition to imaging and serology, identification of E. multilocularis infection via PCR or a histological examination of a tissue biopsy from the person is another way to diagnose alveolar echinococcosis.

This is the main way that PE is diagnosed, but some current studies show that PCR may identify E. oligarthrus and E. vogeli in people's tissues.

Most of these various methods try to prevent and control CE by targeting the major risk factors for the disease and the way it is transmitted.

In addition to targeting risk factors and transmission, control and prevention strategies of cystic echinococcosis also aim at intervening at certain points of the parasite's life cycle, in particular, the infection of hosts (especially dogs) that reside with or near humans.

[35] Proper disposal of carcasses and offal after home slaughter is difficult in poor and remote communities and therefore dogs readily have access to offal from livestock, thus completing the parasite cycle of Echinococcus granulosus and putting communities at risk of cystic echinococcosis.

Boiling livers and lungs that contain hydatid cysts for 30 minutes has been proposed as a simple, efficient, and energy- and time-saving way to kill the infectious larvae.

This is probably because polycystic echinococcosis is restricted to Central and South America and the way that humans become accidental hosts of E. oligarthrus and E. vogeli is still not completely understood.

[40] The radical technique (total cystopericystectomy) is preferable because of its lower risk for postoperative abdominal infection, biliary fistula, and overall morbidity.

PAIR is a minimally invasive procedure that involves three steps: puncture and needle aspiration of the cyst, injection of a scolicidal solution for 20–30 min, and cyst-re-aspiration and final irrigation.

[19][38] There have been several studies that suggest that PAIR with medical therapy is more effective than surgery in terms of disease recurrence, and morbidity and mortality.

[19] For alveolar echinococcosis, surgical removal of cysts combined with chemotherapy (using albendazole and/or mebendazole) for up to two years after surgery is the only sure way to completely cure the disease.

Since chemotherapy on its own is not guaranteed to be completely rid of the disease, people are often kept on the drugs for extended periods (i.e. more than 6 months, years).

[21] For instance, until the end of the 1980s, E. multilocularis endemic areas in Europe were known to exist only in France, Switzerland, Germany, and Austria.

But during the 1990s and early 2000s, there was a shift in the distribution of E. multilocularis as the infection rate of foxes escalated in certain parts of France and Germany.

[47][48] While alveolar echinococcosis is not extremely common, it is believed that in the coming years, it will be an emerging or re-emerging disease in certain countries as a result of E. multilocularis’ ability to spread.

[49] Unlike the previous two species of Echinococcus, E. vogeli and E. oligarthrus are limited to Central and South America.

Then, in 1766, Pierre Simon Pallas predicted that these hydatid cysts found in infected humans were larval stages of tapeworms.

Half a century later, during the 1850s, Karl von Siebold showed through a series of experiments that Echinococcus cysts do cause adult tapeworms in dogs.

Then, during the early to mid-1900s, the more distinct features of E. granulosus and E. multilocularis, their life cycles, and how they cause disease were more fully described as more and more people began researching and performing experiments and studies.

[11][53][54] Two calcified objects recovered from a 3rd- to 4th-century grave of an adolescent in Amiens (Northern France) were interpreted as probable hydatid cysts.