Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

[25] While people with ADHD often struggle to initiate work and persist on tasks with delayed consequences, this may not be evident in contexts they find intrinsically interesting and immediately rewarding,[17][26] a symptom colloquially known as hyperfocus.

[16][22] It represents the extreme lower end of the continuous dimensional trait (bell curve) of executive functioning and self-regulation, which is supported by twin, brain imaging and molecular genetic studies.

[8] However, in rare cases, ADHD can be caused by a single event including traumatic brain injury,[40][45][46][47] exposure to biohazards during pregnancy,[8] or a major genetic mutation.

[71] An association between ADHD and hyperfocus, a state characterised by intense and narrow concentration on a specific stimulus, object or task for a prolonged period of time,[72] has been widely reported in the popular science press and media.

[73] The phenomenon generally occurs when an individual is engaged in activities they find highly interesting, or which provide instant gratification, such as video games or online chatting.

The symptoms of ADHD and PTSD can have significant behavioural overlap—in particular, motor restlessness, difficulty concentrating, distractibility, irritability/anger, emotional constriction or dysregulation, poor impulse control, and forgetfulness are common in both.

[131] In March 2022, JAMA Psychiatry published a systematic review and meta-analysis of 87 studies with 159,425 subjects 12 years of age or younger that found a small but statistically significant correlation between screen time and ADHD symptoms in children.

However, the relationship between ADHD and suicidal spectrum behaviours remains unclear due to mixed findings across individual studies and the complicating impact of comorbid psychiatric disorders.

The remaining 20-30% of variance is mediated by de-novo mutations and non-shared environmental factors that provide for or produce brain injuries; there is no significant contribution of the rearing family and social environment.

[150] In November 1999, Biological Psychiatry published a literature review by psychiatrists Joseph Biederman and Thomas Spencer found the average heritability estimate of ADHD from twin studies to be 0.8,[151] while a subsequent family, twin, and adoption studies literature review published in Molecular Psychiatry in April 2019 by psychologists Stephen Faraone and Henrik Larsson that found an average heritability estimate of 0.74.

However, smaller studies have shown that genetic polymorphisms in genes related to catecholaminergic neurotransmission or the SNARE complex of the synapse can reliably predict a person's response to stimulant medication.

[189][better source needed] In other cases, it may be explained by increasing academic expectations, with a diagnosis being a method for parents in some countries to obtain extra financial and educational support for their child.

[191] The dopamine and norepinephrine pathways that originate in the ventral tegmental area and locus coeruleus project to diverse regions of the brain and govern a variety of cognitive processes.

The degree of hyperconnectivity between these regions correlated with the severity of inattention or hyperactivity[198] Hemispheric lateralization processes have also been postulated as being implicated in ADHD, but empiric results showed contrasting evidence on the topic.

[15][16] The executive function impairments that occur in ADHD individuals result in problems with staying organised, time keeping, procrastination control, maintaining concentration, paying attention, ignoring distractions, regulating emotions, and remembering details.

[205] Due to the rates of brain maturation and the increasing demands for executive control as a person gets older, ADHD impairments may not fully manifest themselves until adolescence or even early adulthood.

[14] Conversely, brain maturation trajectories, potentially exhibiting diverging longitudinal trends in ADHD, may support a later improvement in executive functions after reaching adulthood.

They attest that the disorder is considered valid because: 1) well-trained professionals in a variety of settings and cultures agree on its presence or absence using well-defined criteria and 2) the diagnosis is useful for predicting a) additional problems the patient may have (e.g., difficulties learning in school); b) future patient outcomes (e.g., risk for future drug abuse); c) response to treatment (e.g., medications and psychological treatments); and d) features that indicate a consistent set of causes for the disorder (e.g., findings from genetics or brain imaging), and that professional associations have endorsed and published guidelines for diagnosing ADHD.

[211] The ASEBA, BASC, CHAOS, CRS, and Vanderbilt diagnostic rating scales allow for both parents and teachers as raters in the diagnosis of childhood and adolescent ADHD.

[214][215][216] A 2024 systematic review concluded that the use of biomarkers such as blood or urine samples, electroencephalogram (EEG) markers, and neuroimaging such as MRIs, in diagnosis for ADHD remains unclear; studies showed great variability, did not assess test-retest reliability, and were not independently replicable.

[57]: 10 Some symptoms that are viewed superficially due to anxiety disorders, intellectual disability or the effects of substance abuse such as intoxication and withdrawal can overlap to some extent with ADHD.

[255] The medications for ADHD appear to alleviate symptoms via their effects on the pre-frontal executive, striatal and related regions and networks in the brain; usually by increasing neurotransmission of norepinephrine and dopamine.

[261] Magnetic resonance imaging studies suggest that long-term treatment with amphetamine or methylphenidate decreases abnormalities in brain structure and function found in subjects with ADHD.

[290] There are indications suggesting that stimulant therapy for children and adolescents should be stopped periodically to assess continuing need for medication, decrease possible growth delay, and reduce tolerance.

[57]: 13 Atomoxetine alleviates ADHD symptoms through norepinephrine reuptake and by indirectly increasing dopamine in the pre-frontal cortex,[258] sharing 70-80% of the brain regions with stimulants in their produced effects.

A 2024 systematic review and meta analysis commissioned by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) identified seven studies on the effectiveness of physical exercise for treating ADHD symptoms.

[211] Dietary modifications are not recommended as of 2019[update] by the American Academy of Pediatrics, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, or the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality due to insufficient evidence.

[22][227] The negative impacts of ADHD symptoms contribute to poor health-related quality of life that may be further exacerbated by, or may increase the risk of, other psychiatric conditions such as anxiety and depression.

[338] Although the study did not pinpoint exact causes of death, it highlighted that individuals with ADHD were more likely to engage in smoking, alcohol misuse, and face other health challenges such as depression, self-harm, or personality disorders.

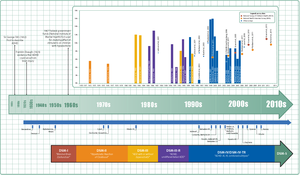

[362][354] The terminology used to describe the condition has changed over time and has included: minimal brain dysfunction in the DSM-I (1952), hyperkinetic reaction of childhood in the DSM-II (1968), and attention-deficit disorder with or without hyperactivity in the DSM-III (1980).