Hyperreal number

[3] The hyperreal numbers satisfy the transfer principle, a rigorous version of Leibniz's heuristic law of continuity.

Concerns about the soundness of arguments involving infinitesimals date back to ancient Greek mathematics, with Archimedes replacing such proofs with ones using other techniques such as the method of exhaustion.

This put to rest the fear that any proof involving infinitesimals might be unsound, provided that they were manipulated according to the logical rules that Robinson delineated.

One immediate application is the definition of the basic concepts of analysis such as the derivative and integral in a direct fashion, without passing via logical complications of multiple quantifiers.

, where st(⋅) denotes the standard part function, which "rounds off" each finite hyperreal to the nearest real.

Similarly, the integral is defined as the standard part of a suitable infinite sum.

This ability to carry over statements from the reals to the hyperreals is called the transfer principle.

Each real set, function, and relation has its natural hyperreal extension, satisfying the same first-order properties.

Similarly, the casual use of 1/0 = ∞ is invalid, since the transfer principle applies to the statement that zero has no multiplicative inverse.

One of the key uses of the hyperreal number system is to give a precise meaning to the differential operator d as used by Leibniz to define the derivative and the integral.

Then, The use of the standard part in the definition of the derivative is a rigorous alternative to the traditional practice of neglecting the square [citation needed] of an infinitesimal quantity.

After the third line of the differentiation above, the typical method from Newton through the 19th century would have been simply to discard the dx2 term.

The use of the definite article the in the phrase the hyperreal numbers is somewhat misleading in that there is not a unique ordered field that is referred to in most treatments.

However, a 2003 paper by Vladimir Kanovei and Saharon Shelah[8] shows that there is a definable, countably saturated (meaning ω-saturated but not countable) elementary extension of the reals, which therefore has a good claim to the title of the hyperreal numbers.

Furthermore, the field obtained by the ultrapower construction from the space of all real sequences, is unique up to isomorphism if one assumes the continuum hypothesis.

The essence of the axiomatic approach is to assert (1) the existence of at least one infinitesimal number, and (2) the validity of the transfer principle.

When Newton and (more explicitly) Leibniz introduced differentials, they used infinitesimals and these were still regarded as useful by later mathematicians such as Euler and Cauchy.

Berkeley's criticism centered on a perceived shift in hypothesis in the definition of the derivative in terms of infinitesimals (or fluxions), where dx is assumed to be nonzero at the beginning of the calculation, and to vanish at its conclusion (see Ghosts of departed quantities for details).

When in the 1800s calculus was put on a firm footing through the development of the (ε, δ)-definition of limit by Bolzano, Cauchy, Weierstrass, and others, infinitesimals were largely abandoned, though research in non-Archimedean fields continued (Ehrlich 2006).

However, in the 1960s Abraham Robinson showed how infinitely large and infinitesimal numbers can be rigorously defined and used to develop the field of nonstandard analysis.

Hyper-real fields were in fact originally introduced by Hewitt (1948) by purely algebraic techniques, using an ultrapower construction.

This turns the set of such sequences into a commutative ring, which is in fact a real algebra A.

From an algebraic point of view, U allows us to define a corresponding maximal ideal I in the commutative ring A (namely, the set of the sequences that vanish in some element of U), and then to define *R as A/I; as the quotient of a commutative ring by a maximal ideal, *R is a field.

They form a ring, that is, one can multiply, add and subtract them, but not necessarily divide by a non-zero element.

is N (the set of all natural numbers), so: Now the idea is to single out a bunch U of subsets X of N and to declare that

Such ultrafilters are called trivial, and if we use it in our construction, we come back to the ordinary real numbers.

Now if we take a nontrivial ultrafilter (which is an extension of the Fréchet filter) and do our construction, we get the hyperreal numbers as a result.

It can be proven by bisection method used in proving the Bolzano-Weierstrass theorem, the property (1) of ultrafilters turns out to be crucial.

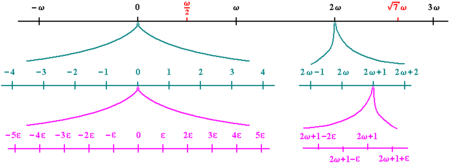

The map st is continuous with respect to the order topology on the finite hyperreals; in fact it is locally constant.

An important special case is where the topology on X is the discrete topology; in this case X can be identified with a cardinal number κ and C(X) with the real algebra Rκ of functions from κ to R. The hyperreal fields we obtain in this case are called ultrapowers of R and are identical to the ultrapowers constructed via free ultrafilters in model theory.