The Method of Mechanical Theorems

The Method of Mechanical Theorems (Greek: Περὶ μηχανικῶν θεωρημάτων πρὸς Ἐρατοσθένη ἔφοδος), also referred to as The Method, is one of the major surviving works of the ancient Greek polymath Archimedes.

[1][2] The work was originally thought to be lost, but in 1906 was rediscovered in the celebrated Archimedes Palimpsest.

The palimpsest includes Archimedes' account of the "mechanical method", so called because it relies on the center of weights of figures (centroid) and the law of the lever, which were demonstrated by Archimedes in On the Equilibrium of Planes.

In these treatises, he proves the same theorems by exhaustion, finding rigorous upper and lower bounds which both converge to the answer required.

Instead, the Archimedean method mechanically balances the parabola (the curved region being integrated above) with a certain triangle that is made of the same material.

The center of mass of a triangle can be easily found by the following method, also due to Archimedes.

, each segment has equal length on opposite sides of the median, so balance follows by symmetry.

This argument can be easily made rigorous by exhaustion by using little rectangles instead of infinitesimal lines, and this is what Archimedes does in On the Equilibrium of Planes.

The total torque exerted by the triangle is its area, 1/2, times the distance 2/3 of its center of mass from the fulcrum at

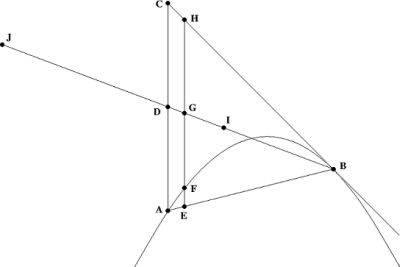

Suppose the line segment AC is parallel to the axis of symmetry of the parabola.

[3] As Archimedes had previously shown, the center of mass of the triangle is at the point I on the "lever" where DI :DB = 1:3.

The mass of this cross section, for purposes of balancing on a lever, is proportional to the area:

Archimedes then considered rotating the triangular region between y = 0 and y = x and x = 2 on the x-y plane around the x-axis, to form a cone.

So if slices of the cone and the sphere both are to be weighed together, the combined cross-sectional area is:

If the two slices are placed together at distance 1 from the fulcrum, their total weight would be exactly balanced by a circle of area

This means that the cone and the sphere together, if all their material were moved to x = 1, would balance a cylinder of base radius 1 and length 2 on the other side.

Archimedes could also find the volume of the cone using the mechanical method, since, in modern terms, the integral involved is exactly the same as the one for area of the parabola.

The dependence of the volume of the sphere on the radius is obvious from scaling, although that also was not trivial to make rigorous back then.

By scaling the dimensions linearly Archimedes easily extended the volume result to spheroids.

He considered this argument to be his greatest achievement, requesting that the accompanying figure of the balanced sphere, cone, and cylinder be engraved upon his tombstone.

To find the surface area of the sphere, Archimedes argued that just as the area of the circle could be thought of as infinitely many infinitesimal right triangles going around the circumference (see Measurement of the Circle), the volume of the sphere could be thought of as divided into many cones with height equal to the radius and base on the surface.

Let the surface of the sphere be S. The volume of the cone with base area S and height r is

One of the remarkable things about the Method is that Archimedes finds two shapes defined by sections of cylinders, whose volume does not involve

This is a central point of the investigation—certain curvilinear shapes could be rectified by ruler and compass, so that there are nontrivial rational relations between the volumes defined by the intersections of geometrical solids.

Archimedes emphasizes this in the beginning of the treatise, and invites the reader to try to reproduce the results by some other method.

Unlike the other examples, the volume of these shapes is not rigorously computed in any of his other works.

From fragments in the palimpsest, it appears that Archimedes did inscribe and circumscribe shapes to prove rigorous bounds for the volume, although the details have not been preserved.

The two shapes he considers are the intersection of two cylinders at right angles (the bicylinder), which is the region of (x, y, z) obeying:

For the intersection of two cylinders, the slicing is lost in the manuscript, but it can be reconstructed in an obvious way in parallel to the rest of the document: if the x-z plane is the slice direction, the equations for the cylinder give that

Jan Hogendijk argues that, besides the volume of the bicylinder, Archimedes knew its surface area, which is also rational.