Hyperspectral imaging

[4] Engineers build hyperspectral sensors and processing systems for applications in astronomy, agriculture, molecular biology, biomedical imaging, geosciences, physics, and surveillance.

If the scanner detects a large number of fairly narrow frequency bands, it is possible to identify objects even if they are only captured in a handful of pixels.

If the pixels are too small, then the intensity captured by each sensor cell is low, and the decreased signal-to-noise ratio reduces the reliability of measured features.

These systems have the drawback of having the image analyzed per lines (with a push broom scanner) and also having some mechanical parts integrated into the optical train.

Although originally developed for mining and geology (the ability of hyperspectral imaging to identify various minerals makes it ideal for the mining and oil industries, where it can be used to look for ore and oil),[11][21] it has now spread into fields as widespread as ecology and surveillance, as well as historical manuscript research, such as the imaging of the Archimedes Palimpsest.

Organizations such as NASA and the USGS have catalogues of various minerals and their spectral signatures, and have posted them online to make them readily available for researchers.

On a smaller scale, NIR hyperspectral imaging can be used to rapidly monitor the application of pesticides to individual seeds for quality control of the optimum dose and homogeneous coverage.

In Australia, work is under way to use imaging spectrometers to detect grape variety and develop an early warning system for disease outbreaks.

[24] On a smaller scale, NIR hyperspectral imaging can be used to rapidly monitor the application of pesticides to individual seeds for quality control of the optimum dose and homogeneous coverage.

[25] Another application in agriculture is the detection of animal proteins in compound feeds to avoid bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), also known as mad-cow disease.

HSI cameras can also be used to detect stress from heavy metals in plants and become an earlier and faster alternative to post-harvest wet chemical methods.

[27][28] Hyperspectral imaging is also used in zoology; it is used to investigate the spatial distribution of coloration and its extension into the near-infrared and SWIR range of the spectrum.

[29][30] Hyperspectral imaging can provide information about the chemical constituents of materials which makes it useful for waste sorting and recycling.

and Optina Diagnostics[37] to test the use of hyperspectral photography in the diagnosis of retinopathy and macular edema before damage to the eye occurs.

[39][40] By improving the accuracy of defect and FM removal, the food processor’s objective is to enhance product quality and increase yields.

Adopting hyperspectral imaging on digital sorters achieves non-destructive, 100 percent inspection in-line at full production volumes.

The sorter’s software compares the hyperspectral images collected to user-defined accept/reject thresholds, and the ejection system automatically removes defects and foreign material.

The recent commercial adoption of hyperspectral sensor-based food sorters is most advanced in the nut industry where installed systems maximize the removal of stones, shells and other foreign material (FM) and extraneous vegetable matter (EVM) from walnuts, pecans, almonds, pistachios, peanuts and other nuts.

Here, improved product quality, low false reject rates and the ability to handle high incoming defect loads often justify the cost of the technology.

Commercial adoption of hyperspectral sorters is also advancing at a fast pace in the potato processing industry where the technology promises to solve a number of outstanding product quality problems.

Work is under way to use hyperspectral imaging to detect “sugar ends,”[41] “hollow heart”[42] and “common scab,”[43] conditions that plague potato processors.

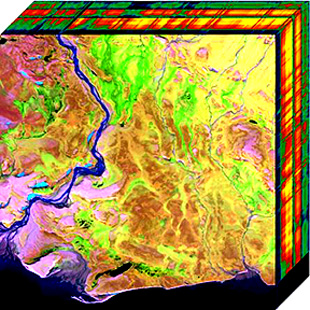

Geological samples, such as drill cores, can be rapidly mapped for nearly all minerals of commercial interest with hyperspectral imaging.

Currently, progress is towards understanding the relationship between oil and gas leakages from pipelines and natural wells, and their effects on the vegetation and the spectral signatures.

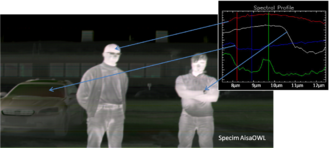

[47] Traditionally, commercially available thermal infrared hyperspectral imaging systems have needed liquid nitrogen or helium cooling, which has made them impractical for most surveillance applications.

In 2010, Specim introduced a thermal infrared hyperspectral camera that can be used for outdoor surveillance and UAV applications without an external light source such as the sun or the moon.

[56] The primary advantage to hyperspectral imaging is that, because an entire spectrum is acquired at each point, the operator needs no prior knowledge of the sample, and postprocessing allows all available information from the dataset to be mined.

Significant data storage capacity is necessary since uncompressed hyperspectral cubes are large, multidimensional datasets, potentially exceeding hundreds of megabytes.