IAU definition of planet

[7] With the discovery of Pluto by Clyde Tombaugh in 1930, astronomers considered the Solar System to have nine planets, along with thousands of smaller bodies such as asteroids and comets.

By measuring Charon's orbital period, astronomers could accurately calculate Pluto's mass for the first time, which they found to be much smaller than expected.

[9] Pluto's mass was roughly one twenty-fifth of Mercury's, making it by far the smallest planet, smaller even than the Earth's Moon, although it was still over ten times as massive as the largest asteroid, Ceres.

New York City's newly renovated Hayden Planetarium did not include Pluto in its exhibit of the planets when it reopened as the Rose Center for Earth and Space in 2000.

After the discovery of Sedna, it set up a 19-member committee in 2005, with the British astronomer Iwan Williams in the chair, to consider the definition of a planet.

It proposed three definitions that could be adopted: Another committee, chaired by a historian of astronomy, Owen Gingerich, a historian and astronomer emeritus at Harvard University who led the committee which generated the original definition, and consisting of five planetary scientists and the science writer Dava Sobel, was set up to make a firm proposal.

Mike Brown, the discoverer of Sedna and Eris, has said that at least 53 known bodies in the Solar System probably fit the definition, and that a complete survey would probably reveal more than 200.

Other planetary satellites (such as the Moon or Ganymede) might be in hydrostatic equilibrium, but would still not have been defined as a component of a double planet, since the barycenter of the system lies within the more massive celestial body.

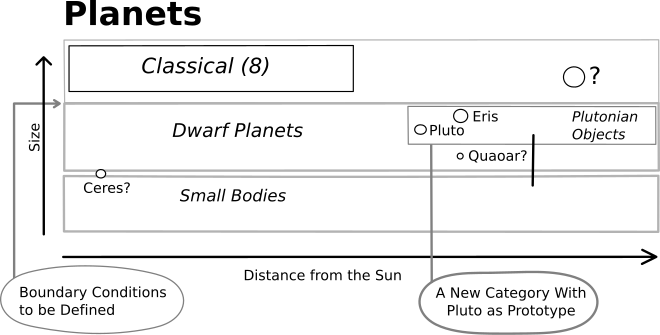

The term "minor planet" would have been abandoned, replaced by the categories "small Solar System body" (SSSB) and a new classification of "pluton".

[15] Such a definition of the term "planet" could also have led to changes in classification for the trans-Neptunian objects Haumea, Makemake, Sedna, Orcus, Quaoar, Varuna, 2002 TX300, Ixion, and 2002 AW197, and the asteroids Vesta, Pallas, and Hygiea.

On 18 August the Committee of the Division of Planetary Sciences (DPS) of the American Astronomical Society endorsed the draft proposal.

According to an IAU draft resolution, the roundness condition generally results in the need for a mass of at least 5×1020 kg, or diameter of at least 800 km.

[23] The proposed definition found support among many astronomers as it used the presence of a physical qualitative factor (the object being round) as its defining feature.

Most other potential definitions depended on a limiting quantity (e.g., a minimum size or maximum orbital inclination) tailored for the Solar System.

However, a similar situation already applies to the term 'moon'—such bodies ceasing to be moons on being ejected from planetary orbit—and this usage has widespread acceptance.

There had also been criticism of the proposed definition of double planet: at present the Moon is defined as a satellite of the Earth, but over time the Earth-Moon barycenter will drift outwards (see tidal acceleration) and could eventually become situated outside of both bodies.

The time taken for this to occur, however, would be billions of years, long after many astronomers expect the Sun to expand into a red giant and destroy both Earth and Moon.

[31] According to Alan Boss of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, a subgroup of the IAU met on August 18, 2006, and held a straw poll on the draft proposal: Only 18 were in favour of it, with over 50 against.

The 50 in opposition preferred an alternative proposal drawn up by Uruguayan astronomers Gonzalo Tancredi and Julio Ángel Fernández.

(3) All the other natural objects orbiting the Sun that do not fulfill any of the previous criteria shall be referred to collectively as "Small Solar System Bodies".

Many geologists had been critical of the choice of name for Pluto-like planets,[35] being concerned about the term pluton, which has been used for years within the geological community to represent a form of magmatic intrusion; such formations are fairly common balls of rock.

[citation needed] Later on August 22, two open meetings were held which ended in an abrupt about-face on the basic planetary definition.

The position of astronomer Julio Ángel Fernández gained the upper hand among the members attending and was described as unlikely to lose its hold by August 24.

[40] The discussion at the first meeting was heated and lively, with IAU members in vocal disagreement with one another over such issues as the relative merits of static and dynamic physics; the main sticking point was whether or not to include a body's orbital characteristics among the definition criteria.

In an indicative vote, members heavily defeated the proposals on Pluto-like objects and double planet systems, and were evenly divided on the question of hydrostatic equilibrium.

[41] At the second meeting of the day, following "secret" negotiations, a compromise began to emerge after the Executive Committee moved explicitly to exclude consideration of extra-solar planets and to bring into the definition a criterion concerning the dominance of a body in its neighbourhood.

Following a reversion to the previous rules on 15 August, as a planetary definition is a primarily scientific matter, every individual member of the Union attending the Assembly was eligible to vote.

In an accompanying press release, the IAU said that:[52] Plutoids are celestial bodies in orbit around the Sun at a distance greater than that of Neptune that have sufficient mass for their self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces so that they assume a hydrostatic equilibrium (near-spherical) shape, and that have not cleared the neighbourhood around their orbit.This subcategory includes Pluto, Haumea, Makemake and Eris.

[55] Astronomer Marla Geha has clarified that not all members of the Union were needed to vote on the classification issue: only those whose work is directly related to planetary studies.

The decision was important enough to prompt the editors of the 2007 edition of the World Book Encyclopedia to hold off printing until a final result had been reached.