Ian Smith

Smith became deputy prime minister following the Front's December 1962 election victory, and he stepped up to the premiership after Field resigned in April 1964, two months before the first events that led to the Bush War took place.

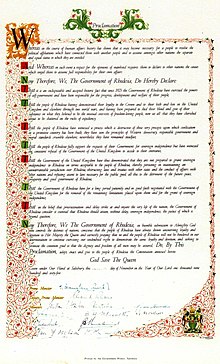

After repeated talks with British prime minister Harold Wilson broke down, Smith and his Cabinet unilaterally declared independence on 11 November 1965 in an effort to delay majority rule; shortly afterwards, the first phase of the war began in earnest.

[6] His critics, in turn, have condemned him as "an unrepentant racist ... who brought untold suffering to millions of Zimbabweans," as the leader of a white supremacist government responsible for maintaining racial inequality and discriminating against the black majority.

"[47] Because of Southern Rhodesia's small size and lack of major controversies, its unicameral parliament then sat only twice a year, for about three months in total, holding discussions in the afternoons either side of a half-hour break for tea on the lawn.

He lent his support to the "United Group", an awkward coalition wherein Winston Field's conservative Dominion Party closed ranks with Sir Robert Tredgold and other liberals against the constitutional proposals, despite opposing them for totally contradictory reasons.

[73] As the UK government granted majority rule in Nyasaland and made moves towards the same in Northern Rhodesia, Smith decided that the Federation was a lost cause and resolved to found a new party that would push for Southern Rhodesian independence without acquiescing to British demands.

He banned the main nationalist group, the National Democratic Party, for being violent and intimidatory—it reformed overnight as the Zimbabwe African People's Union[n 11]—and announced that the UFP would repeal the racially discriminatory Land Apportionment Act if it won the next election, as an attempt to appeal to newly enfranchised blacks.

[90] The Field Cabinet made Southern Rhodesian independence on Federal dissolution its first priority,[90] but the Conservative government in the UK was reluctant to grant this under the 1961 constitution as it knew doing so would lead to censure and loss of prestige in the United Nations (UN) and the Commonwealth.

[94] According to Smith, Field, Dupont and other RF politicians, Butler made several oral independence guarantees to ensure Southern Rhodesia's attendance and support at the conference, but repeatedly refused to give anything on paper.

[n 16] Smith's fellow former UFP men made up most of the new RF Cabinet, with Harper and the Minister of Agriculture, the Duke of Montrose (also called Lord Graham), heading a minority of hardline Dominion Party veterans.

[129] From June, a peripheral dispute concerned Rhodesia's unilateral and ultimately successful attempt to open an independent mission in Lisbon; Portugal's acceptance of this in September 1965 prompted British outrage and Rhodesian delight.

He proposed a Royal Commission to test public opinion in Rhodesia regarding independence under the 1961 constitution, and suggested that the UK might safeguard black representation in the Rhodesian parliament by withdrawing relevant devolved powers.

Security Council Resolutions 216 and 217, adopted in the days following Smith's declaration, denounced UDI as an illegitimate "usurpation of power by a racist settler minority", and called on nations not to entertain diplomatic or economic relations.

[146] Wilson predicted in January 1966 that the various boycotts would force Smith to give in "within a matter of weeks rather than months",[147] but the British (and later UN) sanctions had little effect on Rhodesia, largely because South Africa and Portugal went on trading with it, providing it with oil and other key resources.

[164] Warning that "grave actions must follow",[164] Wilson took the Rhodesia problem to the United Nations, which proceeded to institute the first mandatory trade sanctions in its history with Security Council Resolutions 232 (December 1966) and 253 (April 1968).

A panel of judges headed by Sir Hugh Beadle ruled UDI, the 1965 constitution and Smith's government to be de jure,[n 26] prompting the UK Commonwealth Secretary George Thomson to accuse them of breaching "the fundamental laws of the land".

[182] The Pearce Commission finished its work on 12 March 1972 and published its report two months later—it described white, coloured and Asian Rhodesians as in favour of the terms by 98%, 97% and 96% respectively, and black citizens as against them by an unspecified large majority.

"[195] The geopolitical situation tilted further against Smith in December 1974 when the South African Prime Minister B. J. Vorster pressured him into accepting a détente initiative involving the Frontline States of Zambia, Tanzania and Botswana (Mozambique and Angola would join the following year).

[198] Détente forced a ceasefire, giving the guerrillas time to regroup, and required the Rhodesians to release the ZANU and ZAPU leaders so they could attend a conference in Rhodesia, united under the UANC banner and led by Muzorewa.

[199] When Rhodesia stopped releasing black-nationalist prisoners on the grounds that ZANLA and ZIPRA were not observing the ceasefire, Vorster harried Smith further by withdrawing the South African Police, which had been helping the Rhodesians patrol the countryside.

[201] Nkomo remained unchallenged at the head of ZAPU, but the ZANU leadership had become contested between its founding president, the Reverend Ndabaningi Sithole, and Robert Mugabe, a former teacher from Mashonaland who had recently won an internal election in prison.

[214] In March 1978, Smith and non-militant nationalist groups headed by Muzorewa, Sithole and Chief Jeremiah Chirau agreed what became the "Internal Settlement", under which the country would be reconstituted as Zimbabwe Rhodesia in June 1979 after multiracial elections.

[236] The UK government and the international community ultimately declared the February 1980 general election free and fair,[237] though many observers attested to widespread political violence and intimidation of voters, particularly by ZANU (which added Patriotic Front to its name to become "ZANU–PF").

"[277] He dedicated much of his 1997 autobiography, The Great Betrayal,[n 34] to criticising the Mugabe administration and a long succession of British figures he considered to have let him and Rhodesia down; he also defended and justified his actions as prime minister,[279] and praised Nelson Mandela, calling him Africa's "first black statesman".

[287] Smith had by this time lost most of his former international prominence—his visit to the UK in 2004 to meet Conservative politicians was largely ignored by the British press[289]—but he achieved new domestic popularity and eminence among Zimbabwean opposition supporters, who came to see him as an unbreakable, defiant symbol of resistance to the Mugabe government.

"[291] Bill Schwarz took a similar line, writing that Smith and his supporters reacted to the British Empire's demise by imagining white Rhodesians to be "the final survivors of a lost civilisation",[306] charged with "tak[ing] on the mantle of historic Britain" in the imperial power's absence.

[308] The wartime plastic surgery that corrected the wounds to his face left its right side paralysed, giving him a crooked smile and a somewhat blank expression, while his bodily injuries gave him a stoop and a slight limp;[309] he also could not sit for long periods without pain.

[309] In contrast, his open, informal association with the general public fostered the impression among white Rhodesians that their prime minister was still an "ordinary, decent fellow", which Berlyn cites as a major factor in his enduring popularity.

"[309] Reflecting his divisive legacy, Smith's death ignited mixed reactions in Zimbabwe: then-Deputy Minister of Information Bright Matonga was reported as saying "Good riddance" during a radio appearance, later telling Reuters that he would "not be mourned or missed here by any decent person".

[317] Reactions from the Zimbabwean public differed: reflecting the country's economic downturn under Mugabe, members interviewed by media outlet The Week expressed nostalgia for his premiership as one of stability and prosperity, while simultaneously remembering his strident opposition to majority rule.