Iceland hotspot

[13]: 73–74 This coincides with the opening of the north Atlantic in the late Paleocene and early Eocene, which has led to suggestions that the arrival of the plume was linked to, and has perhaps contributed to, the breakup of[14] Laurasia.

[17] The initial plume head may have been several thousand kilometers in diameter, and it erupted volcanic rocks on both sides of the present ocean basin to produce the North Atlantic Igneous Province.

The excess magmatism that accompanied the transition from flood volcanism on Greenland, Ireland and Norway to present-day Icelandic activity was the result of ascent of the hot mantle source beneath progressively thinning lithosphere, according to the plume model, or a postulated unusually productive part of the mid-ocean ridge system.

[18] Some geologists have suggested that the Iceland plume could have been responsible for the Paleogene uplift of the Scandinavian Mountains by producing changes in the density of the lithosphere and asthenosphere during the opening of the North Atlantic.

[19] To the south the Paleogene uplift of the English chalklands that resulted in the formation of the Sub-Paleogene surface has also been attributed to the Iceland plume.

The oldest crust of Iceland is more than 20 million years old and was formed at an old oceanic spreading center in the Westfjords (Vestfirðir) region.

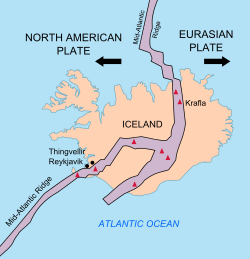

[13]: 74 The westward movement of the plates and the ridge above the plume and the strong thermal anomaly of the latter caused this old spreading center to cease 15 million years ago and lead to the formation of a new one in the area of today's peninsulas Skagi and Snæfellsnes; in the latter there is still some activity in the form of the Snæfellsjökull volcano.

The spreading center, and hence the main activity, shifted eastward again 9 to 7 million years ago and formed the current volcanic zones in the south–west (Reykjanes, Hofsjökull) and north–east (Tjörnes).

Presently, a slow decrease of the activity in the north–east takes place, while the volcanic zone in the south–east (Katla, Vatnajökull), which was initiated 3 million years ago, develops.

[23] This convection mechanism is probably not strong enough under the conditions prevailing in the north Atlantic, with respect to the spreading rate, and it does not offer a simple explanation for the observed geoid anomaly.

For the investigation of postulated plumes, gravimetric, geoid and in particular seismological methods along with geochemical analyses of erupted lavas have proven especially useful.

Regional studies from the 1990s and 2000s show that there is a low seismic-wave-speed anomaly beneath Iceland, but opinion is divided as to whether it continues deeper than the mantle transition zone at roughly 600 km (370 mi) depth.

These values are consistent with a small percentage of partial melt, a high magnesium content of the mantle, or elevated temperature.

[28] The variations in the concentrations of trace elements such as helium, lead, strontium, neodymium, and others show clearly that Iceland is compositionally distinct from the rest of the north Atlantic.

Depending on which elements are considered and how large the area covered is, one can identify up to six different mantle components, which are not all present in any single location.

[30][31] The presence of such a large amount of water in the source of the lavas would tend to lower its melting point and make it more productive for a given temperature.

A study on the Borgarhraun basalt flow helped to constrain the velocity of magma transport from great depths to the surface.