Indistinguishable particles

[1] There are two main categories of identical particles: bosons, which can share quantum states, and fermions, which cannot (as described by the Pauli exclusion principle).

For example, the indistinguishability of particles has been proposed as a solution to Gibbs' mixing paradox.

The first method relies on differences in the intrinsic physical properties of the particles, such as mass, electric charge, and spin.

If differences exist, it is possible to distinguish between the particles by measuring the relevant properties.

However, as far as can be determined, microscopic particles of the same species have completely equivalent physical properties.

What follows is an example to make the above discussion concrete, using the formalism developed in the article on the mathematical formulation of quantum mechanics.

Let n denote a complete set of (discrete) quantum numbers for specifying single-particle states (for example, for the particle in a box problem, take n to be the quantized wave vector of the wavefunction.)

The quantum state of the system is denoted by the expression where the order of the tensor product matters ( if

This is known as the Pauli exclusion principle, and it is the fundamental reason behind the chemical properties of atoms and the stability of matter.

It appears to be a fact of nature that identical particles do not occupy states of a mixed symmetry, such as There is actually an exception to this rule, which will be discussed later.

The corresponding eigenvectors are the symmetric and antisymmetric states: In other words, symmetric and antisymmetric states are essentially unchanged under the exchange of particle labels: they are only multiplied by a factor of +1 or −1, rather than being "rotated" somewhere else in the Hilbert space.

As a result, it can be regarded as an observable of the system, which means that, in principle, a measurement can be performed to find out if a state is symmetric or antisymmetric.

Mathematically, this says that the state vector is confined to one of the two eigenspaces of P, and is not allowed to range over the entire Hilbert space.

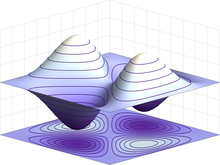

The nature of symmetric states has important consequences for the statistical properties of systems composed of many identical bosons.

Antisymmetry gives rise to the Pauli exclusion principle, which forbids identical fermions from sharing the same quantum state.

Note that Σn mn = N. In the same vein, fermions occupy totally antisymmetric states: Here, sgn(p) is the sign of each permutation (i.e.

The sum has to be restricted to ordered values of m1, ..., mN to ensure that each multi-particle state is not counted more than once.

For instance, if a particle is in a state |ψ⟩, the probability of finding it in a region of volume d3x surrounding some position x is As a result, the continuous eigenstates |x⟩ are normalized to the delta function instead of unity: Symmetric and antisymmetric multi-particle states can be constructed from continuous eigenstates in the same way as before.

This is the manifestation of symmetry and antisymmetry in the wavefunction representation: The many-body wavefunction has the following significance: if the system is initially in a state with quantum numbers n1, ..., nN, and a position measurement is performed, the probability of finding particles in infinitesimal volumes near x1, x2, ..., xN is The factor of N!

comes from our normalizing constant, which has been chosen so that, by analogy with single-particle wavefunctions, Because each integral runs over all possible values of x, each multi-particle state appears N!

Because it is usually more convenient to work with unrestricted integrals than restricted ones, the normalizing constant has been chosen to reflect this.

The correct partition function is Note that this "high temperature" approximation does not distinguish between fermions and bosons.

The discrepancy in the partition functions of distinguishable and indistinguishable particles was known as far back as the 19th century, before the advent of quantum mechanics.

Roughly speaking, bosons have a tendency to clump into the same quantum state, which underlies phenomena such as the laser, Bose–Einstein condensation, and superfluidity.

Fermions, on the other hand, are forbidden from sharing quantum states, giving rise to systems such as the Fermi gas.

Note that the probability of finding particles in the same state is relatively larger than in the distinguishable case.

In a flat d-dimensional space M, at any given time, the configuration of two identical particles can be specified as an element of M × M. If there is no overlap between the particles, so that they do not interact directly, then their locations must belong to the space [M × M] \ {coincident points}, the subspace with coincident points removed.

This is described by the infinite cyclic group generated by making a counterclockwise half-turn interchange.

Unlike the previous case, performing this interchange twice in a row does not recover the original state; so such an interchange can generically result in a multiplication by exp(iθ) for any real θ (by unitarity, the absolute value of the multiplication must be 1).

In fact, even with two distinguishable particles, even though (x, y) is now physically distinguishable from (y, x), the universal covering space still contains infinitely many points which are physically indistinguishable from the original point, now generated by a counterclockwise rotation by one full turn.