Ideal gas

Generally, a gas behaves more like an ideal gas at higher temperature and lower pressure,[2] as the potential energy due to intermolecular forces becomes less significant compared with the particles' kinetic energy, and the size of the molecules becomes less significant compared to the empty space between them.

One mole of an ideal gas has a volume of 22.71095464... L (exact value based on 2019 revision of the SI)[3] at standard temperature and pressure (a temperature of 273.15 K and an absolute pressure of exactly 105 Pa).

[note 1] The ideal gas model tends to fail at lower temperatures or higher pressures, when intermolecular forces and molecular size becomes important.

At some point of low temperature and high pressure, real gases undergo a phase transition, such as to a liquid or a solid.

The model of an ideal gas, however, does not describe or allow phase transitions.

The deviation from the ideal gas behavior can be described by a dimensionless quantity, the compressibility factor, Z.

(If the pressure of a real gas is reduced in a throttling process, its temperature either falls or rises, depending on whether its Joule–Thomson coefficient is positive or negative.)

Both are essentially the same, except that the classical thermodynamic ideal gas is based on classical statistical mechanics, and certain thermodynamic parameters such as the entropy are only specified to within an undetermined additive constant.

The results of the quantum Boltzmann gas are used in a number of cases including the Sackur–Tetrode equation for the entropy of an ideal gas and the Saha ionization equation for a weakly ionized plasma.

Real fluids at low density and high temperature approximate the behavior of a classical ideal gas.

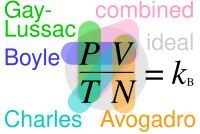

This equation is derived from After combining three laws we get That is: The other equation of state of an ideal gas must express Joule's second law, that the internal energy of a fixed mass of ideal gas is a function only of its temperature, with

For the present purposes it is convenient to postulate an exemplary version of this law by writing: where That U for an ideal gas depends only on temperature is a consequence of the ideal gas law, although in the general case ĉV depends on temperature and an integral is needed to compute U.

In order to switch from macroscopic quantities (left hand side of the following equation) to microscopic ones (right hand side), we use where The probability distribution of particles by velocity or energy is given by the Maxwell speed distribution.

The following three assumptions are very related: molecules are hard, collisions are elastic, and there are no inter-molecular forces.

The dimensionless heat capacity[broken anchor] at constant volume is generally defined by where S is the entropy.

Since the heat capacity depends on the atomic or molecular nature of the gas, macroscopic measurements on heat capacity provide useful information on the microscopic structure of the molecules.

The ratio of the constant volume and constant pressure heat capacity is the adiabatic index For air, which is a mixture of gases that are mainly diatomic (nitrogen and oxygen), this ratio is often assumed to be 7/5, the value predicted by the classical Equipartition Theorem for diatomic gases.

Using the results of thermodynamics only, we can go a long way in determining the expression for the entropy of an ideal gas.

We will be able to derive both the ideal gas law and the expression for internal energy from it.

Since the entropy is an exact differential, using the chain rule, the change in entropy when going from a reference state 0 to some other state with entropy S may be written as ΔS where: where the reference variables may be functions of the number of particles N. Using the definition of the heat capacity at constant volume for the first differential and the appropriate Maxwell relation for the second we have: Expressing CV in terms of ĉV as developed in the above section, differentiating the ideal gas equation of state, and integrating yields: which implies that the entropy may be expressed as: where all constants have been incorporated into the logarithm as f(N) which is some function of the particle number N having the same dimensions as VTĉV in order that the argument of the logarithm be dimensionless.

Mathematically: From this we find an equation for the function f(N) Differentiating this with respect to a, setting a equal to 1, and then solving the differential equation yields f(N): where Φ may vary for different gases, but will be independent of the thermodynamic state of the gas.

In the above "ideal" development, there is a critical point, not at absolute zero, at which the argument of the logarithm becomes unity, and the entropy becomes zero.

The above equation is a good approximation only when the argument of the logarithm is much larger than unity – the concept of an ideal gas breaks down at low values of V/N.

The thermodynamic potentials for an ideal gas can now be written as functions of T, V, and N as: where, as before, The most informative way of writing the potentials is in terms of their natural variables, since each of these equations can be used to derive all of the other thermodynamic variables of the system.

In terms of their natural variables, the thermodynamic potentials of a single-species ideal gas are: In statistical mechanics, the relationship between the Helmholtz free energy and the partition function is fundamental, and is used to calculate the thermodynamic properties of matter; see configuration integral for more details.

The speed of sound in an ideal gas is given by the Newton-Laplace formula: where the isentropic Bulk modulus

, therefore Here, In the above-mentioned Sackur–Tetrode equation, the best choice of the entropy constant was found to be proportional to the quantum thermal wavelength of a particle, and the point at which the argument of the logarithm becomes zero is roughly equal to the point at which the average distance between particles becomes equal to the thermal wavelength.