Safavid conversion of Iran to Shia Islam

Following their rise to power in Iran in the 16th century, the Safavid dynasty initiated a campaign of forced conversion against the Iranian populace, seeking to replace Sunni Islam as the nation's religious majority.

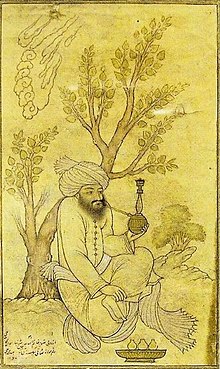

The political climate of 18th-century Iran, the intellectual history of Twelver Shia Islam, and the final Shi'itization of the nation were all greatly influenced by the Shaykh al-Islam Mohammad-Baqer Majlesi.

The order grew more violent under Shaykh Junayd (died 1460), adopting an extreme brand of Shia Islam that included shamanic and animal-based components, such as the belief in metempsychosis and reincarnation, as well as the idea of a Mahdi.

"[9] Mustawfi wrote that Sunni populations were dominant in major cities, while Twelver Shia Islam was concentrated in regions like Gilan, Mazandaran, Ray, Varamin, Qom, Kashan, Khuzestan, and Sabzevar in Khorasan.

[12] In addition to the risky actions of the Qizilbash under Ismail I's command, his support of Arab Shia jurists, initially from northern Syria and then from southern Iraq and the Arabian Peninsula, enhanced his anti-Sunni policies.

During his journey to Isfahan in 1524, the Portuguese traveler António Tenreiro, described witnessing bones protruding from the ground, which he believed to be the remains of 5,000 individuals who had been burned alive by the Safavids.

The Safavids revitalized the Guarded Domains of Iran,[17] a concept formed by a feeling of territorial and political uniformity in a society with shared cultural elements such as the Persian language, monarchy, and Shia Islam.

[26] Makhdum Sharifi Shirazi was the grandson of Tahmasp I's vizier Qadi Jahan Qazvini and claimed the prominent Sunni scholar al-Sharif al-Jurjani as his ancestor.

Building a strong relationship with Ismail II, he was appointed as the co-sadr (highest religious authority) with Shah Enayatollah Esfahani, who had previously served as the military chaplain under Tahmasp I.

Abd-al-Ali ibn Nur-al-Din Ali al-Karaki and Sayyed Hosayn Karaki, two prominent Shia clerics in Qazvin, faced persecution, humiliation, and were ultimately forced to leave the city.

[27] During debates, Ismail II actively supported Sunni arguments against the Shia ulama multiple times, thus weakening their standing and making them targets of mockery.

[21] Ismail II's pro-Sunni policies led to the royal family and Qizilbash poisoning the opium he consumed on 24 November 1577, leading to his death the following day.

It covered topics such as Islamic customs, the correct birth and death dates of the Imams, monetary donations, sales, marriage, divorce, vows, atonement, and criminal law.

Abbas I instructed that Jame-e Abbasi be delivered in "a clear, comprehensible language in order that all people, the learned and the lay, would seek benefit from it," in a deliberate attempt to provide an example of Persianized Shia Islam to the Iranians.

He may not have been as intolerant as he commonly is described, as implied by his trust in the Sunni grand vizier Fath-Ali Khan Daghestani, his interest when visiting to the churches of New Jolfa, as well as the numerous decrees (farman) he declared, which protected the Christian population of Iran and allowed missionaries to perform their work.

These actions included the forced conversion of Zoroastrians, turning their temple in Isfahan into a mosque, exacting jizya (poll tax) from Jews and Christians, and making it illegal for non-Shias to go outside during rain for fear that they might pollute Shias.

Due to increased taxes and endangerment by a law that permitted the family member of an apostate to gain their belongings, several wealthy Armenians withdrew much of their financial assets and left for the Italian cities of Venice and Rome.

[32] The Shaykh al-Islam Mohammad-Baqer Majlesi had a strong influence over Soltan Hoseyn, who frequently sought his advice, maintained constant communication, and asked him to write religious treatises.

However, due in large part to the destruction caused by the Afghans, Isfahan lost its appeal as a major intellectual hub of the Shia world, and instead the shrine cities in Iraq (Najaf, Karbala, Kadhimiya, and Samarra) received more attention.

Masquerading with their madrasa (religious school) education, they displayed an anti-intellectual attitude through a strong focus on hadith, conservatism, ritualistic practices in Shia Islam, opposition against diversity, and a heavy emphasis on the stories of the Imams' suffering.

Sometimes, disagreements emerged over practices such as wine consumption, the support of activities prohibited in Islam like music and painting, and the atypical sexual behaviors within the royal family.

Rituals like bodily cleansing, an obsession with impurities, and detailed rules for prayer and fasting were, in the jurists' view, essential to true faith and used to control the public.

As the moral police of the state, the ulama controlled education and free time, encouraged faithfulness, and reinforced the gap between the "saved" Shia and the "damned" beliefs.

They also denounced breaking traditional sexual standards, women stepping outside of the harem, the drinking of wine (which was frequently portrayed in art of the time), and, most all, the overlooking of religious rituals in public.

Instead of mosques and stories of Shia hardship, many Muslims instead chose to go to public spaces and coffee shops, so that they could listen to the narration of the Persian epic poem Shahnameh by storytellers.

Stories of the adventures of Rostam, such as his fight with the Div-e Sepid on Mount Damavand, as well as the romance about the Sasanian ruler Khosrow II (r. 590–628) and princess Shirin by Nizami Ganjavi, were among the tales they could hear.

[39] The Amilis (and Arab scholars from other regions) were intentionally placed in important religious and quasi-administrative positions by the early Safavid Shahs, so that they could spread their well-defined Islamic creed rooted in the Shia school of thought (madhhab).

In order to gain authority and instill public compliance to clerical decisions across different ethnic and social groups, the Amilis would borrow aspects of Iran's culture.

In recent scholarship, greater attention has been given to the increasing influence of the Mazandarani religious elite within the Safavid state, a subject historically overshadowed by the focus on theologians from Jabal Amil.

[46] The emergence of the Safavid state and its adoption of Shia Islam as the official faith was a pivotal moment that significantly affected both Iran and the surrounding Sunni-majority regions.