Immunoglobulin M

[3][4] In 1937, an antibody was observed in horses hyper-immunized with pneumococcus polysaccharide that was much larger in size than the typical rabbit γ-globulin,[5] with a molecular weight of 990,000 daltons.

[7] In the 1960s, methods were developed for inducing immunoglobulin-producing tumors (plasmacytomas) in mice, thus providing a source of homogeneous immunoglobulins of various isotypes, including IgM (reviewed in[8]).

More recently, the expression of engineered immunoglobulin genes in tissue culture can be used to produce IgM with specific alterations and thus to identify the molecular requirements for features of interest.

The oligosaccharides on mouse and human IgM have been partially characterized by a variety of techniques, including NMR, lectin binding, various chromatographic systems, and enzymatic sensitivity (reviewed in[9]).

The heavy and light chains are held together both by disulfide bonds (depicted as red triangles) and by non-covalent interactions.

On the basis of its sedimentation velocity and appearance in electron micrographs, it was inferred that IgM usually occurs as a "pentamer", i.e., a polymer composed of five “monomers” [(μL)2]5, and was originally depicted by the models in Figures 1C and 1D, with disulfide bonds between the Cμ3 domains and between the tail pieces.

[29] Conversely, cells expressing a γ heavy chain that has been modified to include the tailpiece produce polymeric IgG.

[34][35][36][37] The wide range might be due to technical problems, such as incomplete radiolabeling or imprecisely quantitating an Ouchterlony line.

Individual C2, C3, and C4tp domains were generated independently in E. coli and then studied using a range of approaches, including sedimentation rate, X-ray crystallography, and NMR spectroscopy, to obtain insight into the detailed three-dimensional structure of the chain.

Such effects are well illustrated by experiments involving immunization with xenogenic (foreign) erythrocytes (red blood cells).

For example, when IgG is administered together with xenogenic erythrocytes, this combination causes almost complete suppression of the erythrocyte-specific antibody response.

This effect is used clinically to prevent Rh-negative mothers from becoming immunized against fetal Rh-positive erythrocytes, and its use has dramatically decreased the incidence of hemolytic disease in newborns.

[43] In contrast to the effect of IgG, antigen-specific IgM can greatly enhance the antibody response, especially in the case of large antigens.

[citation needed] In germ-line cells (sperm and ova) the genes that will eventually encode immunoglobulins are not in a functional form (see V(D)J recombination).

The expression of the other isotypes (γ, ε and α) is affected by another type of DNA rearrangement, a process called Immunoglobulin class switching.

This phenomenon is probably due to the high avidity of IgM that allows it to bind detectably even to weakly cross-reacting antigens that are naturally occurring.

For example, the IgM antibodies that bind to the red blood cell A and B antigens might be formed in early life as a result of exposure to A- and B-like substances that are present in bacteria or perhaps also in plant materials.

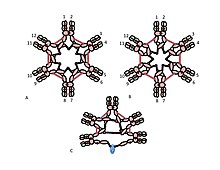

A) The μL heterodimer, sometimes called a halfmer, with variable (VH, VL) and constant region (Cμ1, Cμ2, Cμ3, Cμ4tp; CL) domains. The cysteines that mediate disulfide bonds between μ chains are shown as red arrowheads, so that a cysteine disulfide bond appears as a red double arrowhead (red diamond). [ citation needed ]

B) The IgM “monomer” (μL)2. The disulfide bonds between Cμ2 domains are represented by a red double arrowhead.

C, D) Two models for J chain-containing IgM pentamer that have appeared in various publications at various times. As in (B), the disulfide bonds between Cμ2 domains and the disulfide bonds between Cμ4tp domains are represented by a red double arrowhead; the Cμ3 disulfide bonds are represented (for clarity) by long double-headed arrows. The connectivity, i.e., the inter-chain disulfide bonding of the μ chains, is denoted like electrical connectivity. In (C) the Cμ3 disulfide bonds join μ chains in parallel with the Cμ4tp disulfide bonds, and these disulfide bonds join μ chains in series with the Cμ2 disulfide bonds. In (D) the Cμ2 and Cμ4tp disulfide bonds join μ chains in parallel and both types join μ chains in series with the Cμ3 disulfide bonds. (Figure reproduced with permission of the publisher and authors [ 10 ] ).

A, B) These figures depict two of many possible models of inter-μ chain disulfide bonding in hexameric IgM. As in Figure 1, the Cμ2 disulfide bonds and the Cμ4tp disulfide bonds are represented by a red double arrowhead, and the Cμ3 disulfide bonds are represented by the long double-headed arrows. In both models A and B each type of disulfide bond (Cμ2-Cμ2; Cμ3-Cμ3; Cμ4tp-Cμ4tp) joins μ chains eries with each of the others. Methods for distinguishing these and other models are discussed in reference [28].

C) This representation of pentameric IgM illustrates how the J chain might be bonded to μ chains that are not linked via Cμ3 disulfide bonds