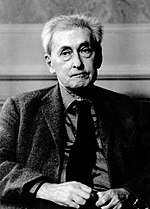

Ilya Ehrenburg

His incendiary articles calling for violence against Germans during the Great Patriotic War won him a huge following among front-line Soviet soldiers, but also caused much controversy due to their perceived anti-German sentiment.

Ehrenburg's travel writing also had great resonance, and to an arguably greater extent, so did his memoir People, Years, Life, which may be his best known and most discussed work.

He began to write poems, regularly visited the cafés of Montparnasse and got acquainted with a lot of artists, especially Pablo Picasso, Diego Rivera, Jules Pascin, and Amedeo Modigliani.

He wrote avant-garde picaresque novels and short stories popular in the 1920s, often set in Western Europe (The Extraordinary Adventures of Julio Jurenito and his Disciples (1922), Thirteen Pipes[7]).

He had written a pamphlet which said, among other things, that surrealists shunned work, favouring parasitism, and that they endorsed "onanism, pederasty, fetishism, exhibitionism, and even sodomy".

[11] Ehrenburg was offered a column in Krasnaya Zvezda (the Red Army newspaper) days after the German invasion of the Soviet Union.

[13] In 1943, Ehrenburg, working with the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, began to collect material for what would become The Black Book of Soviet Jewry, documenting The Holocaust.

[14][15] As a consequence, he is one of many Soviet writers, along with Konstantin Simonov and Alexey Surkov, who many have accused of "[lending] their literary talents to the hate campaign" against Germans.

[16] Austrian historian Arnold Suppan argued that Ehrenburg "agitated in the style of Nazi racist ideology", with statements such as: The Germans are not humans.

[18] Ehrenburg later accompanied the Soviet forces during the East Prussian Offensive and criticized the indiscriminate violence against German civilians, for which he was reprimanded by Stalin.

[20][14] In January 1945, Adolf Hitler stated that "Stalin's court lackey, Ilya Ehrenburg, declares that the German people must be exterminated".

[23][24] On 21 September 1948, at the behest of Politburo members Lazar Kaganovich and Georgy Malenkov, Ehrenburg published an article in Pravda[25] which signified Stalin's absolute political break with Israel, which he had been supporting through enormous shipments of Czech arms.

Ilya Ehrenburg's name was high on a list presented to Stalin by the chief of police, Viktor Abakumov, of people selected for arrest.

[citation needed] During a press conference in London in 1950, attended by over 200 journalists, he was challenged about the fate of the writers David Bergelson and Itzik Feffer, and said that "If anything unpleasant had happened to them, I would have known", knowing that they were both under arrest.

[citation needed] In February 1953, he refused to denounce the supposed doctors' plot and wrote a letter to Stalin opposing collective punishment of Jews.

It portrayed a corrupt and despotic factory boss, a "little Stalin", and told the story of his wife, who increasingly feels estranged from him, and the views he represents.

In the novel, the spring thaw comes to represent a period of change in the characters' emotional journeys, and when the wife eventually leaves her husband, this coincides with the melting of the snow.

In August 1954, Konstantin Simonov attacked The Thaw in articles published in Literaturnaya Gazeta, arguing that such writings are too dark and do not serve the Soviet state.

In this book, Ehrenburg was the first legal Soviet author to mention positively a lot of names banned under Stalin, including Marina Tsvetaeva.

[31] In January 1963, the critic Vladimir Yermilov wrote a long article in Izvestia in which he picked up on Ehrenburg's admission that he had suspected that innocent people were being arrested in 1937 and 1938 but had "gritted his teeth" in silence.

Ehrenburg was also active as a poet till his last days, depicting the events of World War II in Europe, the Holocaust and the destinies of Russian intellectuals.

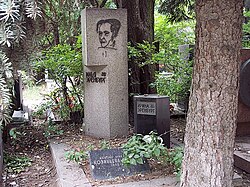

Ehrenburg died in 1967 of prostate and bladder cancer, and was interred in Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow, where his gravestone is etched with a reproduction of his portrait drawn by his friend Pablo Picasso.