Immunity (medicine)

In biology, immunity is the state of being insusceptible or resistant to a noxious agent or process, especially a pathogen or infectious disease.

[2] The adaptive component, on the other hand, involves more advanced lymphatic cells that can distinguish between specific "non-self" substances in the presence of "self".

[4] It does not adapt to specific external stimulus or a prior infection, but relies on genetically encoded recognition of particular patterns.

The prehistoric view was that disease was caused by supernatural forces, and that illness was a form of theurgic punishment for "bad deeds" or "evil thoughts" visited upon the soul by the gods or by one's enemies.

[9] The first written descriptions of the concept of immunity may have been made by the Athenian Thucydides who, in 430 BC, described that when the plague hit Athens: "the sick and the dying were tended by the pitying care of those who had recovered, because they knew the course of the disease and were themselves free from apprehensions.

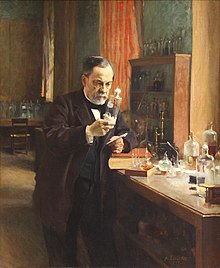

[10] Active immunotherapy may have begun with Mithridates VI of Pontus (120-63 BC)[11] who, to induce active immunity for snake venom, recommended using a method similar to modern toxoid serum therapy, by drinking the blood of animals which fed on venomous snakes.

[11] He is thought to have assumed that those animals acquired some detoxifying property, so that their blood would contain transformed components of the snake venom that could induce resistance to it instead of exerting a toxic effect.

The term "immunes" is also found in the epic poem "Pharsalia" written around 60 BC by the poet Marcus Annaeus Lucanus to describe a North African tribe's resistance to snake venom.

[9] The first clinical description of immunity which arose from a specific disease-causing organism is probably A Treatise on Smallpox and Measles ("Kitab fi al-jadari wa-al-hasbah″, translated 1848[14][15]) written by the Islamic physician Al-Razi in the 9th century.

In the treatise, Al Razi describes the clinical presentation of smallpox and measles and goes on to indicate that exposure to these specific agents confers lasting immunity (although he does not use this term).

The theory viewed diseases such as cholera or the Black Plague as being caused by a miasma, a noxious form of "bad air".

[10] Around the 15th century in India, the Ottoman Empire, and east Africa, the practice of inoculation (poking the skin with powdered material derived from smallpox crusts) was quite common.

To avoid confusion, smallpox inoculation was increasingly referred to as variolation, and it became common practice to use this term without regard for chronology.

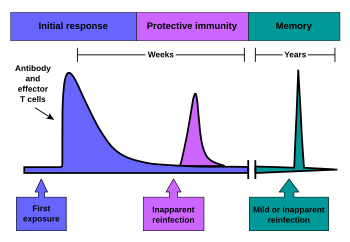

[17] Passive immunity provides immediate protection, but the body does not develop memory, therefore the patient is at risk of being infected by the same pathogen later.

[18] Artificially acquired passive immunity is a short-term immunization induced by the transfer of antibodies, which can be administered in several forms; as human or animal blood plasma, as pooled human immunoglobulin for intravenous (IVIG) or intramuscular (IG) use, and in the form of monoclonal antibodies (MAb).

[18] The artificial induction of passive immunity has been used for over a century to treat infectious disease, and before the advent of antibiotics, was often the only specific treatment for certain infections.

In unmatched donors this type of transfer carries severe risks of graft versus host disease.

The primary and secondary responses were first described in 1921 by English immunologist Alexander Glenny[20] although the mechanism involved was not discovered until later.

When a person is exposed to a live pathogen and develops a primary immune response, this leads to immunological memory.

Live attenuated polio and some typhoid and cholera vaccines are given orally in order to produce immunity based in the bowel.

Numerous immunologic studies and a growing number of epidemiologic studies have shown that vaccinating previously infected individuals significantly enhances their immune response and effectively reduces the risk of subsequent infection, including in the setting of increased circulation of more infectious variants.