Immunological memory

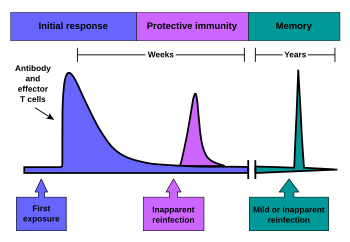

[5] However, antibodies that were previously created in the body remain and represent the humoral component of immunological memory and comprise an important defensive mechanism in subsequent infections.

First, in order to evolve immune memory the initial molecular machinery cost must be high and will demand losses in other host characteristics.

Individuals living in isolated environments such as islands have a less diverse population of memory cells, which are, however, present with sturdier immune responses.

[1] In contrast, the naive plasma cell is fully differentiated and cannot be further stimulated by antigen to divide or increase antibody production.

[3] RAG1-deficient mice without functional T and B cells were able to survive the administration of a lethal dose of Candida albicans when exposed previously to a much smaller amount, showing that vertebrates also retain this ability.

[16] When innate immune cells receive an activation signal; for example, through recognition of PAMPs with PRRs, they start the expression of proinflammatory genes, initiate an inflammatory response, and undergo epigenetic reprogramming.

The interaction of exogenous PAMPs (β-glucan, muramyl peptide) or endogenous DAMPs (oxidized LDL, uric acid) with PRR initiates a cellular response.

An increase in metabolic activity provides cells with energy and building blocks, which are needed for the production of signaling molecules such as cytokines and chemokines.

There is an interplay between metabolism and epigenetic changes because some metabolites such as fumarate and acetyl-CoA can activate or inhibit enzymes involved in chromatin remodeling.

Inflammation is very costly, and increased effectivity of response accelerates pathogen elimination and prevents damage to the host's own tissue.

Classical adaptive immune memory evolved in jawed vertebrates and in jawless fish (lamprey), which is approximately just 1% of living organisms.

In plants and invertebrates, faster kinetics, increased magnitude of immune response and an improved survival rate can be seem after secondary infection encounters.

[21] The emergence of the adaptive immune system is rooted in the deep history of evolution dating back roughly 500 million years.

Early investigations around the 1970s led to the discovery of unique inverted repeat flanking signal sequences while groups studied the RAG genome.

Culmination of several works and review suggests that these disruptions could have been selected for a rearrangement to maintain genomic integrity which ultimately led to mechanisms like RAG diversifications in AIS.

This discovery led to the hypothesis that there was an invasion event of a regulatory element-like region because these repeats resembled a remnant transposable element.

Ohno, 40 years ago proposed that the evolutionary events which led to whole genome duplication was key for the emergence of the diversity we see in adaptive immunity and memory.

[25] Further works illustrate that newer genic regions which arose because of this duplication event, are major contributors to today's adaptive immune systems which control immunological memory in gnathostomes.