Military history of China before 1912

[2] China's armies also benefited from an advanced logistics system as well as a rich strategic tradition, beginning with Sun Tzu's The Art of War, that deeply influenced military thought.

Equipped with bronze weapons, bows, and armor, these armies won victories against the sedentary Dongyi to the East and South, which were the main direction of expansion, as well as defending the western border against the nomadic incursions of the Xirong.

Technological advances such as iron weapons and crossbows put the chariot-riding nobility out of business and favored large, professional standing armies, who were well-supplied and could fight a sustained campaign.

[14] In the field of military planning, the niceties of chivalrous warfare were abandoned in favor of a general who would ideally be a master of maneuver, illusion, and deception.

In order to increase the rapid deployment of troops, thousands of miles of roads were built, along with canals that allowed boats to travel long distances.

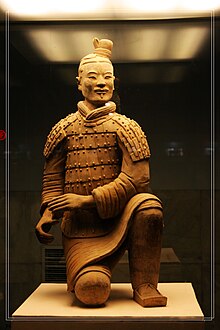

[19] Armies during the Qin and Han dynasties largely inherited their institutions from the earlier Warring States period, with the major exception that cavalry forces were becoming more and more important, due to the threat of the Xiongnu.

[26] A new military system did not come until the invasions of the Xianbei in the 5th century, by which time most of the Wu Hu had been destroyed and much of North China had been reconquered by the Chinese dynasties in the South.

The Song had to rely on new gunpowder weapons introduced during the late Tang and bribes to fend off attacks by its enemies, such as the Liao (Khitans), West Xia (Tanguts), Jin (Jurchens), and Mongol Empire, as well as an expanded army of over 1 million men.

[42] The Song was greatly disadvantaged by the fact their neighbors had taken advantage of the era of chaos following the collapse of the Tang to advance into Northern China unimpeded.

This military technology and prosperous economy were key for the Song army to fend off invaders who could not be bribed with "tribute payments," such as the Khitans and Jur'chens.

[80] At the Guozijian, law, math, calligraphy, equestrianism, and archery were emphasized by the Ming Hongwu Emperor in addition to Confucian classics and also required in the imperial examinations.

Beginning in the 14th century, the Ming armies drove out the Mongols and expanded China's territories to include Yunnan, Mongolia, Tibet, much of Xinjiang and Vietnam.

In 1662, Chinese and European arms clashed when a Ming-loyalist army of 25,000 led by Koxinga forced Dutch East India Company garrison of 2,000 on Taiwan into surrender, after a final assault during a seven-month siege.

The Manchus were a sedentary agricultural people who lived in fixed villages, farmed crops, practiced hunting and mounted archery.,[103] In the late sixteenth century, Nurhaci, founder of the Later Jin dynasty (1616–1636) and originally a Ming vassal, began organizing "Banners", military-social units that included Jurchen, Han Chinese, Korean and Mongol elements under direct command of the Emperor.

Nurhaci married one of his granddaughters to the Ming General Li Yongfang after he surrendered the city of Fushun in Liaoning in 1618 and a mass marriage of Han Chinese officers and officials to Manchu women numbering 1,000 couples was arranged by Prince Yoto and Hongtaiji in 1632 to promote harmony between the two ethnic groups.

Han Chinese who defected up to 1644 and joined the Eight Banners were made bannermen, giving them social and legal privileges in addition to being acculturated to Manchu culture.

Wu then hesitated to go further north, not being able to coordinate strategy with his allies, and the Kangxi Emperor was able to unify his forces for a counterattack led by a new generation of Manchu generals.

[126] During the reign of the Qianlong Emperor in the mid-late 18th century, they launched the Ten Great Campaigns resulting in victories over the Dzungar Khanate and the Kingdom of Nepal; the Manchus drove the Gurkhas out of Tibet and only stopped their chase near Kathmandu.

A British officer said of Qing forces during the First Opium War, "The Chinese are robust muscular fellows, and no cowards; the Tartars desperate; but neither are well commanded nor acquainted with European warfare.

At the assault of the Peiho Forts in 1860 they carried the French ladders to the ditch, and, standing in the water up to their necks, supported them with their hands to enable the storming party to cross.

It was not usual to take them into action; they, however, bore the dangers of a distant fire with the greatest composure, evincing a strong desire to close with their compatriots, and engage them in mortal combat with their bamboos.—(Fisher.

The Tientsin Arsenal developed the capacity to manufacture "electric torpedoes,"[141] that is, what would now be called "mines," US consul general, David Bailey reported that they were deployed in waterways along with other modern military weapons.

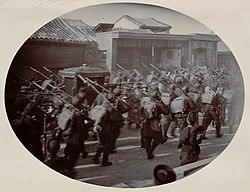

Chinese gingal guns firing massive shells were used accurately, and inflicted severe wounds and death on the Allied troops during the Boxer Rebellion.

For example, during the Boxer Rebellion, in contrast to the Manchu and other Chinese soldiers who used arrows and bows, the Muslim Kansu Braves cavalry had the newest carbine rifles.

Meanwhile, new but not exactly modern Chinese armies suppressed the midcentury rebellions, bluffed Russia into a peaceful settlement of disputed frontiers in Central Asia, and defeated the French forces on land in the Sino-French War (1884–85).

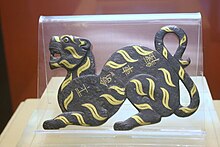

In China, the crossbow was one of the primary military weapons from the Warring States period until the end of the Han dynasty, when armies were composed of up to 30 to 50 percent crossbowmen.

[173] This became partially evident when the Manchus' began to rely on the Jesuits to run their cannon foundry,[2] at a time when European powers had assumed the global lead in gunpowder warfare through their Military Revolution.

Traditionally interpreted as a wind god, a sculpture in Sichuan was found holding a bombard, and the date must be as early as AD 1128[177] These cast-iron hand cannons and erupters were mostly fitted to ships and fortifications for defense.

For example, in the State of Qi during the Spring and Autumn period (771 BC–476 BC), command was delegated to the ruler, the crown prince, and the second son.

By the time of the Warring States period, generals were appointed based on merit rather than birth, the majority of whom were talented individuals who gradually rose through the ranks.