Infantry

The word derives from Middle French infanterie, from older Italian (also Spanish) infanteria (foot soldiers too inexperienced for cavalry), from Latin īnfāns (without speech, newborn, foolish), from which English also gets infant.

Conversely, starting about the mid-19th century, regular cavalry have been forced to spend more of their time dismounted in combat due to the ever-increasing effectiveness of enemy infantry firearms.

But this changed sometime before recorded history; the first ancient empires (2500–1500 BC) are shown to have some soldiers with standardised military equipment, and the training and discipline required for battlefield formations and manoeuvres: regular infantry.

Heavy infantry, such as Greek hoplites, Macedonian phalangites, and Roman legionaries, specialised in dense, solid formations driving into the main enemy lines, using weight of numbers to achieve a decisive victory, and were usually equipped with heavier weapons and armour to fit their role.

Light infantry, such as Greek peltasts, Balearic slingers, and Roman velites, using open formations and greater manoeuvrability, took on most other combat roles: scouting, screening the army on the march, skirmishing to delay, disrupt, or weaken the enemy to prepare for the main forces' battlefield attack, protecting them from flanking manoeuvers, and then afterwards either pursuing the fleeing enemy or covering their army's retreat.

Towards the end of Middle Ages, this began to change, where more professional and better trained light infantry could be effective against knights, such as the English longbowmen in the Hundred Years' War.

Technological developments allowed the raising of large numbers of light infantry units armed with ranged weapons, without the years of training expected for traditional high-skilled archers and slingers.

This started slowly, first with crossbowmen, then hand cannoneers and arquebusiers, each with increasing effectiveness, marking the beginning of early modern warfare, when firearms rendered the use of heavy infantry obsolete.

[citation needed] The modern rifleman infantry became the primary force for taking and holding ground on battlefields as an element of combined arms.

[14] Additional specialised equipment may be required, depending on the mission or to the particular terrain or environment, including satchel charges, demolition tools, mines, or barbed wire, carried by the infantry or attached specialists.

[15] Better infantry equipment to support their health, energy, and protect from environmental factors greatly reduces these rates of loss, and increase their level of effective action.

[16] The pilum was a javelin the Roman legionaries threw just before drawing their primary weapon, the gladius (short sword), and closing with the enemy line.

[citation needed] Infantry have employed many different methods of protection from enemy attacks, including various kinds of armour and other gear, and tactical procedures.

[citation needed] Helmets were added back during World War I as artillery began to dominate the battlefield, to protect against their fragmentation and other blast effects beyond a direct hit.

Modern developments in bullet-proof composite materials like kevlar have started a return to body armour for infantry, though the extra weight is a notable burden.

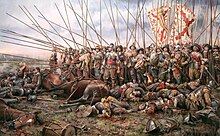

[citation needed] Beginning with the development the first regular military forces, close-combat regular infantry fought less as unorganised groups of individuals and more in coordinated units, maintaining a defined tactical formation during combat, for increased battlefield effectiveness; such infantry formations and the arms they used developed together, starting with the spear and the shield.

[citation needed] Similarly, a shield has decent defence abilities, but is literally hit-or-miss; an attack from an unexpected angle can bypass it completely.

This also increased their shock combat effect; individual opponents saw themselves literally lined-up against several heavy infantryman each, with seemingly no chance of defeating all of them.

Heavy infantry developed into huge solid block formations, up to a hundred meters wide and a dozen rows deep.

Several of these Egyptian "divisions" made up an army, but operated independently, both on the march and tactically, demonstrating sufficient military command and control organisation for basic battlefield manoeuvres.

[21] The antiquity saw everything from the well-trained and motivated citizen armies of Greece and Rome, the tribal host assembled from farmers and hunters with only passing acquaintance with warfare and masses of lightly armed and ill-trained militia put up as a last ditch effort.

Kushite king Taharqa enjoyed military success in the Near East as a result of his efforts to strengthen the army through daily training in long-distance running.

These include, among others, Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear (CBRN) defence and training other airmen in basic ground defense tactics.