Insect physiology

The head comprises six fused segments with compound eyes, ocelli, antennae and mouthparts, which differ according to the insect's particular diet, e.g. grinding, sucking, lapping and chewing.

[2] A general overview of the internal structure and physiology of the insect is presented, including digestive, circulatory, respiratory, muscular, endocrine and nervous systems, as well as sensory organs, temperature control, flight and molting.

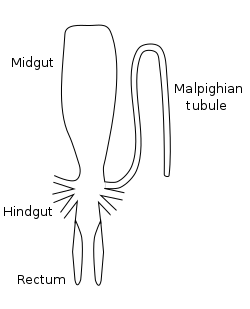

The alimentary canal has specific sections for grinding and food storage, enzyme production, and nutrient absorption.

Saliva mixes with food, which travels through salivary tubes into the mouth, beginning the process of breaking it down.

Making up usually less than 25% of an insect's body weight, it transports hormones, nutrients and wastes and has a role in osmoregulation, temperature control, immunity, storage (water, carbohydrates and fats) and skeletal function.

[7] Regulating chemical exchanges between tissues, hemolymph is encased in the insect body cavity or haemocoel.

[6][7] Body fluids enter through one way valved ostia which are openings situated along the length of the combined aorta and heart organ.

[6][7] The hemolymph is circulated to the appendages unidirectionally with the aid of muscular pumps or accessory pulsatile organs which are usually found at the base of the antennae or wings and sometimes in the legs.

[7] Since oxygen is delivered directly, the circulatory system is not used to carry oxygen, and is therefore greatly reduced; it has no closed vessels (i.e., no veins or arteries), consisting of little more than a single, perforated dorsal tube which pulses peristaltically, and in doing so helps circulate the hemolymph inside the body cavity.

[4] The major tracheae are thickened spirally like a flexible vacuum hose to prevent them from collapsing and often swell into air sacs.

[7] Terrestrial and a large proportion of aquatic insects perform gaseous exchange as previously mentioned under an open system.

Here the tracheae separate peripherally, covering the general body surface which results in a cutaneous form of gaseous exchange.

[7] Muscles can be divided into four categories: Flight has allowed the insect to disperse, escape from enemies and environmental harm, and colonise new habitats.

[2] One of the insect's key adaptations is flight, the mechanics of which differ from those of other flying animals because their wings are not modified appendages.

Outside the pivotal point the downward stroke is generated through contraction of muscles that extend from the sternum to the wing.

[7] Hormones are the chemical substances that are transported in the insect's body fluids (haemolymph) that carry messages away from their point of synthesis to sites where physiological processes are influenced.

[4] It has been suggested that a brain hormone is responsible for caste determination in termites and diapause interruption in some insects.

This is made up of a dendrite with two projections that receive stimuli and an axon, which transmits information to another neuron or organ, like a muscle.

And some, like the house fly Musca domestica, have all the body ganglia fused into a single large thoracic ganglion.

[4] This consists of motor neuron axons that branch out to the muscles from the ganglia of the central nervous system, parts of the sympathetic nervous system and the sensory neurons of the cuticular sense organs that receive chemical, thermal, mechanical or visual stimuli from the insect's environment.

[7] Chemical senses include the use of chemoreceptors, related to taste and smell, affecting mating, habitat selection, feeding and parasite-host relationships.

[2] Chemoreceptor sensitivity related to smell in some substances, is very high and some insects can detect particular odours that are at low concentrations miles from their original source.

[2] Hearing structures or tympanal organs are located on different body parts such as, wings, abdomen, legs and antennae.

[2] The ocelli are unable to form focused images but are sensitive mainly, to differences in light intensity.

Insects are generally considered cold-blooded or ectothermic, their body temperature rising and falling with the environment.

With a short generation time, they evolve faster and can adjust to environmental changes more rapidly than other slower breeding animals.

The opening (gonopore) of the common oviduct is concealed in a cavity called the genital chamber and this serves as a copulatory pouch (bursa copulatrix) when mating.

[4] Insect sexual reproduction starts with sperm entry that stimulates oogenesis, meiosis occurs and the egg moves down the genital tract.

[7] The vas deferentia then unite posteriorally to form a central ejaculatory duct, this opens to the outside on an aedeagus or a penis.

[2] A complex process controlled by hormones, it includes the cuticle of the body wall, the cuticular lining of the tracheae, foregut, hindgut and endoskeletal structures.