Physiology of dinosaurs

[dubious – discuss] However, with the discovery of much more complete skeletons in western United States, starting in the 1870s, scientists could make more informed interpretations of dinosaur biology and physiology.

[1] In parallel, the development of Darwinian evolution, and the discoveries of Archaeopteryx and Compsognathus, led Thomas Henry Huxley to propose that dinosaurs were closely related to birds.

Pioneers in the field, such as William Buckland, Gideon Mantell, and Richard Owen, interpreted the first, very fragmentary remains as belonging to large quadrupedal beasts.

In most of his writings Bakker framed his arguments as new evidence leading to a revival of ideas popular in the late 19th century, frequently referring to an ongoing dinosaur renaissance.

[10] These debates sparked interest in new methods for ascertaining the palaeobiology of extinct animals, such as bone histology, which have been successfully applied to determining the growth-rates of many dinosaurs.

Today, it is generally thought that many or perhaps all dinosaurs had higher metabolic rates than living reptiles, but also that the situation is more complex and varied than Bakker originally proposed.

[14] The feeding habits of ornithomimosaurs and oviraptorosaurs are a mystery: although they evolved from a predatory theropod lineage, they have small jaws and lack the blade-like teeth of typical predators, but there is no evidence of their diet or how they ate and digested it.

The pachycephalosaurs had small heads and weak jaws and teeth, but their lack of large digestive systems suggests a different diet, possibly fruits, seeds, or young shoots, which would have been more nutritious to them than leaves.

[14] It has often been suggested that at least some dinosaurs used swallowed stones, known as gastroliths, to aid digestion by grinding their food in muscular gizzards, and that this was a feature they shared with birds.

Early sexual maturity is also associated with specific features of animals' life cycles: the young are born relatively well-developed rather than helpless; and the death-rate among adults is high.

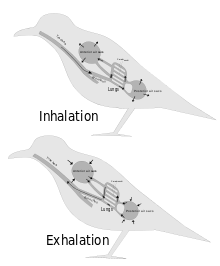

[18] From about 1870 onwards scientists have generally agreed that the post-cranial skeletons of many dinosaurs contained many air-filled cavities (postcranial skeletal pneumaticity, especially in the vertebrae.

For a long time these cavities were regarded simply as weight-saving devices, but Bakker proposed that they were connected to air sacs like those that make birds' respiratory systems the most efficient of all animals'.

[26] Very few formal rebuttals have been published in scientific journals of Ruben et al.'s claim that dinosaurs could not have had avian-style air sacs; but one points out that the Sinosauropteryx fossil on which they based much of their argument was severely flattened and therefore it was impossible to tell whether the liver was the right shape to act as part of a hepatic piston mechanism.

In addition to providing a very efficient supply of oxygen, the rapid airflow would have been an effective cooling mechanism, which is essential for animals that are active but too large to get rid of all the excess heat through their skins.

[35] The palaeontologist Peter Ward has argued that the evolution of the air sac system, which first appears in the very earliest dinosaurs, may have been in response to the very low (11%) atmospheric oxygen of the Carnian and Norian ages of the Triassic Period.

Nasal turbinates are absent or very small in some birds (e.g. ratites, Procellariiformes and Falconiformes) and mammals (e.g. whales, anteaters, bats, elephants, and most primates), although these animals are fully endothermic and in some cases very active.

[50] The original authors defended their position; they agreed that the chest did contain a type of concretion, but one that had formed around and partially preserved the more muscular portions of the heart and aorta.

The huge herbivorous sauropods may have been on the move so constantly in search of food that their energy expenditure would have been much the same irrespective of whether their resting metabolic rates were high or low.

In mid-2008 he co-authored a paper that examined bone samples from a wide range of archosaurs, including early dinosaurs, and concluded that:[71] An osteohistological analysis of vascular density and density, shape and area of osteocytes concluded non-avian dinosaurs and the majority of archosauriforms (except Proterosuchus, crocodilians and phytosaurs) retained heat and had resting metabolic rates similar to those of extant mammals and birds.

[80][81] Studies of the sauropodomorph Massospondylus and early theropod Syntarsus (Megapnosaurus) reveal growth rates of 3 kg/year and 17 kg/year, respectively, much slower than those estimated of Maiasaura and observed in modern birds.

[88] Carrier's constraint states that air-breathing vertebrates with two lungs that flex their bodies sideways during locomotion find it difficult to move and breathe at the same time.

However, despite Carrier's constraint, sprawling limbs are efficient for creatures that spend most of their time resting on their bellies and only move for a few seconds at a time—because this arrangement minimizes the energy costs of getting up and lying down.

This is generally an adaptation to frequent sustained running, characteristic of endotherms which, unlike ectotherms, are capable of producing sufficient energy to stave off the onset of anaerobic metabolism in the muscle.

[100] Dinosaur fossils have been found in regions that were close to the poles at the relevant times, notably in southeastern Australia, Antarctica and the North Slope of Alaska.

Even so, the Alaska North Slope has no fossils of large cold-blooded animals such as lizards and crocodilians, which were common at the same time in Alberta, Montana, and Wyoming.

[105] But a round trip between there and Montana would probably have used more energy than a cold-blooded land vertebrate produces in a year; in other words the Alaskan dinosaurs would have to be warm-blooded, irrespective of whether they migrated or stayed for the winter.

[107][108] It is more difficult to determine the climate of southeastern Australia when the dinosaur fossil beds were laid down 115 to 105 million years ago, towards the end of the Early Cretaceous: these deposits contain evidence of permafrost, ice wedges, and hummocky ground formed by the movement of subterranean ice, which suggests mean annual temperatures ranged between −6 °C (21 °F) and 5 °C (41 °F); oxygen isotope studies of these deposits give a mean annual temperature of 1.5 °C (34.7 °F) to 2.5 °C (36.5 °F).

In living birds and mammals, water loss is limited by pulling moisture out of exhaled air with mucus-covered respiratory turbinates, tissue-covered bony sheets in the nasal cavity.

The most obvious possible answers are: Crocodilians present some puzzles if one regards dinosaurs as active animals with fairly constant body temperatures.

This raises some questions: Modern crocodilians are cold-blooded but can move with their limbs erect, and have several features normally associated with warm-bloodedness because they improve the animal's oxygen supply:[117] So why did natural selection favor these features, which are important for active warm-blooded creatures but of little apparent use to cold-blooded aquatic ambush predators that spend most of their time floating in water or lying on river banks?