Interprovincial migration in Canada

In fact, from the early years of confederation to the 1930s, Quebec and the Maritimes experienced a period of mass emigration to the United States.

[5][6] However, some French Canadians and Maritimers were also drawn to Ontario in the 19th and early 20th centuries, when the development of mining and forestry resources in the northeastern and eastern regions of the province attracted a large workforce.

The agreement for the establishment of the province had included guarantees that the Métis would receive grants of land and that their existing unofficial landholdings would be recognized.

[10] The act gave a claimant 160 acres (or 65 hectares) for free, the only cost to the farmer being a $10 administration fee.

[3] Migration from Atlantic Canada to Ontario and the West in search of economic opportunity is longstanding phenomenon.

Fishing had previously been a major driver of the economies of the Atlantic provinces, and this loss of work proved catastrophic for many families.

[14] This systemic export of labour[15] is explored by author Kate Beaton in her 2022 graphic memoir Ducks, which details her experience working in the Athabasca oil sands.

Inversely, Francophone immigrants living outside Quebec is the group most prone to interprovincial migration, as 9.2% of them move to another province.

The only time the province significantly lost population to this phenomenon was during the 1990s, when it had a negative interprovincial migration for 5 consecutive years.

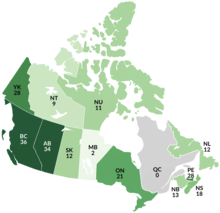

[3] Source: Statistics Canada[2] Manitoba is one of the provinces most affected by interprovincial migration, having had a negative mobility ratio for 42 out of 46 years from 1971 to 2017.

[22] Source: Statistics Canada[2] Since it started being recorded in 1971, Newfoundland and Labrador is the province that has lost the biggest share of its population to interprovincial migration, which was especially high in the 1990s.

Out-migration from the province was curtailed in 2008 and net migration stayed positive through 2014, when it again dropped due to bleak finances and rising unemployment (caused by falling oil prices).

[3] With the announcement of the 2016 provincial budget, St. John's Telegram columnist Russell Wangersky published the column "Get out if you can", which urged young Newfoundlanders to leave the province to avoid future hardships.

[23] In the 2021 Canadian census, Newfoundland and Labrador was the only province which recorded a population decline in the previous five years.

Source: Statistics Canada[2] From 1971 to 2012, Nova Scotia had a persistent negative trend in net interprovincial migration.

In a dramatic shift, by the late 2010s and especially afterward, Nova Scotia became one of the preferred destinations in Canada with significant in-migration, mainly from Ontario.

Over the period from 1971 to 2015, Ontario was the province that experienced the second-lowest levels of interprovincial in-migration and out-migration, second only to Quebec.

[26] Source: Statistics Canada[2] Since it began being recorded in 1971 until 2018, each year Quebec has had negative interprovincial migration, and among the provinces it has experienced the largest net loss of people due to the effect.