Intron

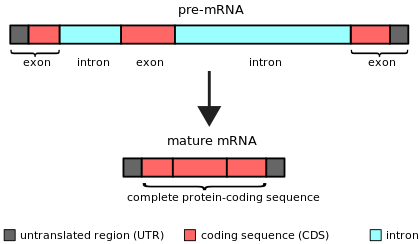

An intron is any nucleotide sequence within a gene that is not expressed or operative in the final RNA product.

Introns are now known to occur within a wide variety of genes throughout organisms, bacteria,[6] and viruses within all of the biological kingdoms.

The fact that genes were split or interrupted by introns was discovered independently in 1977 by Phillip Allen Sharp and Richard J. Roberts, for which they shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1993,[7] though credit was excluded for the researchers and collaborators in their labs that did the experiments resulting in the discovery, Susan Berget and Louise Chow.

(Gilbert 1978)The term intron also refers to intracistron, i.e., an additional piece of DNA that arises within a cistron.

The frequency of introns within different genomes is observed to vary widely across the spectrum of biological organisms.

[13] A particularly extreme case is the Drosophila dhc7 gene containing a ≥3.6 megabase (Mb) intron, which takes roughly three days to transcribe.

[14][15] On the other extreme, a 2015 study suggests that the shortest known metazoan intron length is 30 base pairs (bp) belonging to the human MST1L gene.

Apart from these three short conserved elements, nuclear pre-mRNA intron sequences are highly variable.

In some cases, particular intron-binding proteins are involved in splicing, acting in such a way that they assist the intron in folding into the three-dimensional structure that is necessary for self-splicing activity.

[28] However, these ideal conditions require very close matches to the best splice site sequences and the absence of any competing cryptic splice site sequences within the introns and those conditions are rarely met in large eukaryotic genes that may cover more than 40 kilobase pairs.

It is plausible, then, that the human genome carries a substantial load of suboptimal sequences which cause the generation of aberrant transcript isoforms.

[37][38][39] When the mutant allele is in a heterozygous state this will result in production of two abundant splice variants; one functional and one non-functional.

In the homozygous state the mutant alleles may cause a genetic disease such as the hemophilia found in descendants of Queen Victoria where a mutation in one of the introns in a blood clotting factor gene creates a cryptic 3' splice site resulting in aberrant splicing.

Some introns themselves encode functional RNAs through further processing after splicing to generate noncoding RNA molecules.

Furthermore, some introns play essential roles in a wide range of gene expression regulatory functions such as nonsense-mediated decay[45] and mRNA export.

[46] After the initial discovery of introns in protein-coding genes of the eukaryotic nucleus, there was significant debate as to whether introns in modern-day organisms were inherited from a common ancient ancestor (termed the introns-early hypothesis), or whether they appeared in genes rather recently in the evolutionary process (termed the introns-late hypothesis).

Another theory is that the spliceosome and the intron-exon structure of genes is a relic of the RNA world (the introns-first hypothesis).

[47] There is still considerable debate about the extent to which of these hypotheses is most correct but the popular consensus at the moment is that following the formation of the first eukaryotic cell, group II introns from the bacterial endosymbiont invaded the host genome.

[52] More recent studies of entire eukaryotic genomes have now shown that the lengths and density (introns/gene) of introns varies considerably between related species.

In highly expressed yeast genes, introns inhibit R-loop formation and the occurrence of DNA damage.

Bonnet et al. (2017)[60] speculated that the function of introns in maintaining genetic stability may explain their evolutionary maintenance at certain locations, particularly in highly expressed genes.

[61] Introns may be lost or gained over evolutionary time, as shown by many comparative studies of orthologous genes.

In tandem genomic duplication, due to the similarity between consensus donor and acceptor splice sites, which both closely resemble AGGT, the tandem genomic duplication of an exonic segment harboring an AGGT sequence generates two potential splice sites.

Further genomic analyses, especially when executed at the population level, may then quantify the relative contribution of each mechanism, possibly identifying species-specific biases that may shed light on varied rates of intron gain amongst different species.