Interstate Highway System

Unlike the earlier United States Numbered Highway System, the interstates were designed to be all freeways, with nationally unified standards for construction and signage.

The system has continued to expand and grow as additional federal funding has provided for new routes to be added, and many future Interstate Highways are currently either being planned or under construction.

The system would include two percent of all roads and would pass through every state at a cost of $25,000 per mile ($16,000/km), providing commercial as well as military transport benefits.

Leaving from the Ellipse near the White House on July 7, the Motor Transport Corps convoy needed 62 days to drive 3,200 miles (5,100 km) on the Lincoln Highway to the Presidio of San Francisco along the Golden Gate.

The convoy suffered many setbacks and problems on the route, such as poor-quality bridges, broken crankshafts, and engines clogged with desert sand.

In 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt gave Thomas MacDonald, chief at the Bureau of Public Roads, a hand-drawn map of the United States marked with eight superhighway corridors for study.

[18] In 1954, Eisenhower appointed General Lucius D. Clay to head a committee charged with proposing an interstate highway system plan.

[20]Clay's committee proposed a 10-year, $100 billion program ($1.13 trillion in 2023), which would build 40,000 miles (64,000 km) of divided highways linking all American cities with a population of greater than 50,000.

The bill quickly won approval in the Senate, but House Democrats objected to the use of public bonds as the means to finance construction.

[23] Assisting in the planning was Charles Erwin Wilson, who was still head of General Motors when President Eisenhower selected him as Secretary of Defense in January 1953.

Traveling in either direction, I-70 traffic must exit the freeway and use a short stretch of US 30 (which includes a number of roadside services) to rejoin I-70.

Long-term plans for I-69, which currently exists in several separate completed segments (the largest of which are in Indiana and Texas), is to have the highway route extend from Tamaulipas, Mexico to Ontario, Canada.

The planned I-11 will then bridge the Interstate gap between Phoenix, Arizona and Las Vegas, Nevada, and thus form part of the CANAMEX Corridor (along with I-19, and portions of I-10 and I-15) between Sonora, Mexico and Alberta, Canada.

Political opposition from residents canceled many freeway projects around the United States, including: In addition to cancellations, removals of freeways are planned: The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) has defined a set of standards that all new Interstates must meet unless a waiver from the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) is obtained.

I-93 in Franconia Notch State Park in northern New Hampshire has a speed limit of 45 mph (70 km/h) because it is a parkway that consists of only one lane per side of the highway.

In Savannah, Georgia, and Charleston, South Carolina, in 1999, lanes of I-16 and I-26 were used in a contraflow configuration in anticipation of Hurricane Floyd with mixed results.

Engineers began to apply lessons learned from the analysis of prior contraflow operations, including limiting exits, removing troopers (to keep traffic flowing instead of having drivers stop for directions), and improving the dissemination of public information.

[55] According to urban legend, early regulations required that one out of every five miles of the Interstate Highway System must be built straight and flat, so as to be usable by aircraft during times of war.

[56][57] It is also commonly believed the Interstate Highway System was built for the sole purpose of evacuating cities in the event of nuclear warfare.

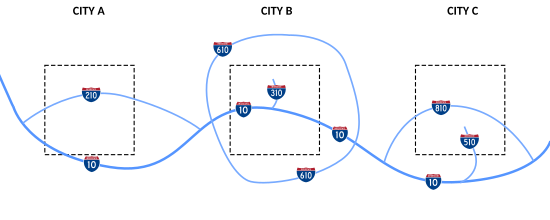

Major west–east arterial Interstates increase in number from I-10 between Santa Monica, California, and Jacksonville, Florida, to I-90 between Seattle, Washington, and Boston, Massachusetts, with two exceptions.

The Interstate Highway System also extends to Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico, even though they have no direct land connections to any other states or territories.

As American suburbs have expanded, the costs incurred in maintaining freeway infrastructure have also grown, leaving little in the way of funds for new Interstate construction.

A notable example is the western approach to the Benjamin Franklin Bridge in Philadelphia, where I-676 has a surface street section through a historic area.

Like other highways, Interstates feature guide signs that list control cities to help direct drivers through interchanges and exits toward their desired destination.

It was granted an exemption in the 1950s due to having an already largely completed and signed highway system; placing exit number signage across the state was deemed too expensive.

Caltrans commonly installs exit number signage only when a freeway or interchange is built, reconstructed, retrofitted, or repaired, and it is usually tacked onto the top-right corner of an already existing sign.

[107][citation needed] Suburbanization became possible, with the rapid growth of larger, sprawling, and more car-dependent housing than was available in central cities, enabling racial segregation by white flight.

[112] In rural areas, towns and small cities off the grid lost out as shoppers followed the interstate and new factories were located near them.

The new system facilitated the relocation of heavy manufacturing to the South and spurred the development of Southern-based corporations like Walmart (in Arkansas) and FedEx (in Tennessee).

[118] Other critics have blamed the Interstate Highway System for the decline of public transportation in the United States since the 1950s,[119] which minorities and low-income residents are three to six times more likely to use.