Intraocular lens

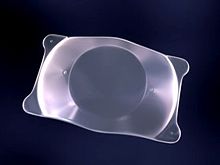

The use of a flexible IOL enables the lens to be rolled for insertion into the capsular bag through a very small incision, thus avoiding the need for stitches.

[citation needed] CLEAR has a 90% success rate (risks include wound leakage, infection, inflammation, and astigmatism).

First, they are an alternative to the excimer laser procedure (LASIK), a form of eye surgery that does not work for people with serious vision problems.

The disadvantage is that the eye's ability to change focus (accommodate) has generally been reduced or eliminated, depending on the kind of lens implanted.

[citation needed] The surgeon can ascertain the astigmatic, or steepest, meridian in a number of ways, including manifest refraction or corneal topography.

Underlying regular astigmatism can also be managed by RLE, even beyond the scope of corneal incisional techniques, by toric lens implants.

The exception are one piece IOLs, which must be placed within the capsular bag at the time of cataract surgery and hence cannot be used as secondary implants.

[citation needed] Pseudophakic IOLs are lenses implanted during cataract surgery, immediately after removal of the patient's crystalline lens.

Patients who undergo a standard IOL implantation no longer experience clouding from cataracts, but they are unable to accommodate (change focus from near to far, far to near, and to distances in between).

monovision, in which one eye is made emmetropic and the other myopic, can partially compensate for the loss of accommodation and enable clear vision at multiple distances.

More versatile types of lenses (multifocal and accommodating IOLs) were introduced in 2003 in the United States, with the approval by the Food and Drug Administration.

However, concentric ring multifocal lenses are prone to glare and mildly compromised focus at all ranges of vision.

[6] The most common adverse visual effects from multifocal IOLs include glare, halos (rings around lights), and a loss of contrast sensitivity in low-light conditions.

An adjustable IOL allows surgeons to implant it and then, once healing is complete, use an ultraviolet light delivery device to fine tune it until it suits the patient.

[14] The eyes and lenses must not be exposed to random ultraviolet light before and during the adjustment process, and protective glasses must be worn from the operation until the lens is locked.

[15] Some newer lens designs attempt to allow the eye to regain some ability to change focus from distance to near (accommodation).

[16] Accommodative intraocular lenses may also have a slightly higher risk of developing posterior capsule opacification (PCO), though there is some uncertainty around this finding.

The hinges are made of an advanced silicone called BioSil that was thoroughly tested to make sure it was capable of unlimited flexing in the eye.

The Crystalens has two hinged struts on opposite edges which displace the lens along the optical axis when an inward transverse force is applied to the haptic loops at the outer ends of the struts (the components transferring the movement of the contact points to the device), and it springs back when the force is reduced.

The elongated zone of focus is intended to prevent the overlapped out-of-focus images of the multifocal lens which cause the halo effect.

Phakic IOLs (PIOLs) are intraocular lenses which are placed in an eye that still contains a natural human crystalline lens.

[22] Depending on their attachment site to the eye, PIOLs can be divided into three categories:[25] In 2006, a centrally perforated ICL (i.e., the Hole-ICL) was created to improve aqueous humour circulation.

Dr. Patrick H. Benz of Benz Research and Development created the first IOL material to incorporate the same UV-A blocking and violet light filtering chromophore that's present in the human crystalline lens in order to attempt to protect the retina after cataract extraction of the natural crystalline lens.

[28] In a small percentage of patients, posterior chamber intraocular lenses may form PCOs a few months after implantation.

Developments in intra-operative wavefront technology have demonstrated power calculations that provide improved outcomes, yielding 80% of patients within 0.5 dioptres (7/7.5 (20/25) or better).

[34] Sir Harold Ridley was the first to successfully implant an intraocular lens on 29 November 1949, at St Thomas' Hospital at London.

[35] That lens was manufactured by the Rayner company of Brighton, East Sussex, England from Perspex CQ polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) made by ICI (Imperial Chemical Industries).

Ridley had observed that Royal Air Force pilots who sustained eye injuries during World War II involving PMMA windshield material did not show any rejection or foreign body reaction, and deduced that the transparent material was inert and useful for implantation in the eye.