History of Ireland

Seafaring raiders and pirates from Scandinavia (later referred to as Vikings), settled from the late 8th century AD which resulted in extensive cultural interchange, as well as innovation in military and transport technology.

However, the nature of Ireland's decentralised political organisation into small territories (known as túatha), martial traditions, difficult terrain and climate and lack of urban infrastructure, meant that attempts to assert Crown authority were slow and expensive.

The new policy fomented the rebellion of the Hiberno-Norman Earl of Kildare Silken Thomas in 1534, keen to defend his traditional autonomy and Catholicism, and marked the beginning of the prolonged Tudor conquest of Ireland lasting from 1536 to 1603.

[4] However a bear bone found in Alice and Gwendoline Cave, County Clare, in 1903 may push back dates for the earliest human settlement of Ireland to 10,500 BC.

It is argued this is when the first signs of agriculture started to show, leading to the establishment of a Neolithic culture, characterised by the appearance of pottery, polished stone tools, rectangular wooden houses, megalithic tombs, and domesticated sheep and cattle.

[10] In Leinster and Munster, individual adult males were buried in small stone structures, called cists, under earthen mounds and were accompanied by distinctive decorated pottery.

[18][22] It is also during the fifth century that the main over-kingdoms of in Tuisceart, Airgialla, Ulaid, Mide, Laigin, Mumhain, Cóiced Ol nEchmacht began to emerge (see Kingdoms of ancient Ireland).

In recent years, some experts have hypothesized that Roman-sponsored Gaelic forces (or perhaps even Roman regulars) mounted some kind of invasion around CE 100,[28] but the exact relationship between Rome and the dynasties and peoples of Hibernia remains unclear.

[29] Perhaps it was some of the latter returning home as rich mercenaries, merchants, or wealth in the form of enslaved people stolen from Britain or Gaul, who first brought the Christian faith to Ireland.

The period of Insular art, mainly in the fields of illuminated manuscripts, metalworking, and sculpture flourished and produced such treasures as the Book of Kells, the Ardagh Chalice, and the many carved stone crosses that dot the island.

These early raids interrupted the golden age of Christian Irish culture and marked the beginning of two centuries of intermittent warfare, with waves of Viking raiders plundering monasteries and towns throughout Ireland.

The second wave of Vikings made stations at winter bases called longphorts to serve as control centres to exert a more localized force on the island through raiding.

[36] Perhaps it was Muircherteach's increasing power in the Isles that led Magnus Barefoot, King of Norway, to lead campaigns against the Irish in 1098 and again in 1102 to bring Norse areas back under Norwegian control, while also raiding the various British kingdoms.

[40] With the authority of the papal bull Laudabiliter from Adrian IV, Henry landed with a large fleet at Waterford in 1171, becoming the first King of England to set foot on Irish soil.

Coupled with the absence of archaeological evidence to the contrary, this has tempted many scholars of medieval western Ireland to agree with the twelfth-century historian Giraldus Cambrensis who argued that the Gaelic kings did not build castles.

The Lordship of Ireland lay in the hands of the powerful Fitzgerald Earl of Kildare, who dominated the country by means of military force and alliances with Irish lords and clans.

After this point, the English authorities in Dublin established real control over Ireland for the first time, bringing a centralised government to the entire island, and successfully disarmed the native lordships.

The wealthier Irish Catholics backed James to try to reverse the Penal laws and land confiscations, whereas Protestants supported William and Mary in this "Glorious Revolution" to preserve their property in the country.

The Penal laws that had been relaxed somewhat after the Restoration were reinforced more thoroughly after this war, as the infant Anglo-Irish Ascendancy wanted to ensure that the Irish Roman Catholics would not be in a position to repeat their rebellions.

Part of the agreement forming the basis of union was that the Test Act would be repealed to remove any remaining discrimination against Roman Catholics, Presbyterians, Baptists and other dissenter religions in the newly United Kingdom.

In addition, the unprecedented threat of Irishmen being conscripted to the British Army in 1918 (for service on the Western Front as a result of the German spring offensive) accelerated this change.

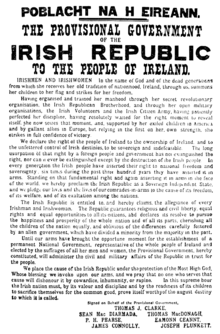

In the December 1918 elections Sinn Féin, the party of the rebels, won three-quarters of all seats in Ireland, twenty-seven MPs of which assembled in Dublin on 21 January 1919 to form a 32-county Irish Republic Parliament, the first Dáil Éireann unilaterally declaring sovereignty over the entire island.

The treaty to sever the Union divided the republican movement into anti-Treaty (who wanted to fight on until an Irish Republic was achieved) and pro-Treaty supporters (who accepted the Free State as the first step towards full independence and unity).

The clergy's influence meant that the Irish state had very conservative social policies, forbidding, for example, divorce, contraception, abortion, pornography as well as encouraging the censoring and banning of many books and films.

Though nominally neutral, recent studies have suggested a far greater level of involvement by the state with the Allies than was realised, with D Day's date set on the basis of secret weather information on Atlantic storms supplied by Ireland.

The violent outbreaks in the late 1960s encouraged and helped strengthen military groups such as the IRA, who served as the protectors of the working class Catholics who were vulnerable to police and civilian brutality.

Moreover, the British Army and the (largely Protestant) Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) also took part in the chaos that resulted in the deaths of over 3,000 men, women and children, civilians and military.

Principal acts were passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom in the same way as for much of the rest of the UK, but many smaller measures were dealt with by Order in Council with minimal parliamentary scrutiny.

Attempts were made to establish a power-sharing executive, representing both the nationalist and unionist communities, by the Northern Ireland Constitution Act of 1973 and the Sunningdale Agreement in December 1973.

However, both the power-sharing Executive and the elected Assembly were suspended between January and May 2000, and from October 2002 until April 2007, following breakdowns in trust between the political parties involving outstanding issues, including "decommissioning" of paramilitary weapons, policing reform and the removal of British Army bases.

Forty years later, Irish Catholics, known as "Jacobites", fought for James from 1688 to 1691, but failed to restore James to the throne of Ireland, England and Scotland.